Life simplifies when you find the right balance.

Women’s roles continue to expand and change, but are still underscored by their ability to “take care” of others. As dentists, we provide for our patients’ oral health care needs. As wives and mothers, we have many other less formally defined care-giving roles. Unfortunately, women ignore the importance of balancing these demands with needed personal care.

We need to take care of ourselves to serve effectively as caretakers. I am reminded of this each time I hear a flight attendant say, “Put your oxygen mask on first, then assist the person next to you.”

The costs of trying to support an unbalanced life can be high. Women often find themselves barreling through their personal and professional lives and scrambling to keep pace with the demands. We might skip the well-balanced diet, exercise, and recreational time, as well as overall healthy lifestyle choices because we think we don’t have time. It should be no surprise, then, that more than 60 percent of women in the United States are overweight, and one-third are clinically obese.2, 3 In addition, one in five women now has cardiovascular disease. Similarly, coronary heart disease now may claim more women’s lives (52 percent of all heart disease deaths), outpacing our male colleagues.4, 5

Dentistry is not a stress-free profession, and stress - personal or professional - can adversely affect our health.6, 7 In the United Kingdom and the United States, more than half of dentists reported tension, headaches, insomnia, or depression as a result of work-related stress.6, 8 Stress is reported across all dental specialties. Its sources include patient-clinician relationships; scheduling, workload, and personal time conflicts; staff and technical problems; and practice-management concerns.9-11

Moreover, the autonomous and demanding nature of dentistry may place women at greater risk of heart disease than their male colleagues.12

Take a balanced view

Balancing the equation between our careers and personal lives can be a challenge. For many, it probably seems easier to ration chocolate! Time is our most precious treasure, and we struggle to decide how to partition it among various activities. Worse, we may interpret “balance” as equal time - an impossible task. We need a healthy mix of work and leisure, as well as give and take. Finding the right blend of personal and professional satisfaction might be more important in relieving stress and the key to obtaining balance.

Take a balanced view

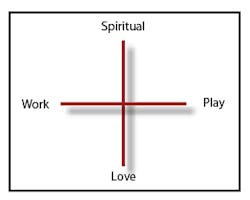

Balance was also central to Dr. L.D. Pankey, a respected icon in our profession who believed that optimal patient care must be individualized and comprehensive, and address all the needs of a patient.13, 14 Dr. Pankey’s philosophy was adapted from Hippocrates’ ancient “cross of life,” in which balance of the four humors was believed to be central to good health.

Represented schematically here, the symbol represents for the caregiver an ideal balanced life, with equilibrium between our professional, recreational, spiritual, and emotional needs. Shown with four equal lines radiating from the center, the symbol shows how our lives go off-kilter when we overemphasize one aspect, such as working too much and playing too little. When this happens, we are unlikely to live healthy and satisfying lives, and we probably will not be useful in caring for others. Fulfillment is achieved when we balance our needs for emotional care (love), spirituality, work, and play.

Find balance

My goal has been to keep this symbol - the cross of life - in balance, despite the demands of family and friends, business and professional issues, health, and community needs that can detour my best intentions. Obtaining balance is challenging. I find it helpful to envision the process as a journey - not a destination - and one that is marked by guideposts of excellence - not perfection.

One of the first steps in taking care of ourselves is to identify what is important. Take time regularly to evaluate and update your professional and personal goals. Make sure these goals (both long-term and short-term) are consistent with your values. For example, a goal of exponentially expanding your practice might not be readily compatible with increasing family time. Establish goals that reflect your role as a dental professional, as well as a wife, mother, and community member, and try to balance those goals.

In my professional journey, I have refocused my goals and priorities several times. During my first 10 years, I practiced dentistry full time and attended continuing education courses frequently. I focused on my fledgling practice for both professional and economic reasons. When my first child was born, I squeezed in only four days of maternity leave. My time off ended immediately after the office baby shower when I discovered I had a patient waiting for a crown adjustment!

During the next 10 years, I focused more time and energy on the needs of my family and the family business. Now, as I enter my third decade in dentistry, I realize that I can’t do everything well - or at least not simultaneously. I also learned, as a parent, that I have only 18 years to raise a child, but 40 years (or more) to practice dentistry.

Manage your time to match your priorities

• Budget your time at work and at home: aim for excellence, not perfection.

• Control interruptions and distractions such as telephone calls during family time and patient care.

• Schedule quiet (and undisturbed) times for important activities involving family or patient care.

• Take personal time for your own emotional and spiritual needs.

• Allocate special time for your family and friends.

• Leave work on time. Try to minimize those “working late” dates and you’ll have more flexibility to meet your goals.

• Think about creative time solutions - flex-time, job sharing, and part time.

• Enjoy your weekends and time off to the fullest.

Recognizing common sources of professional stress and learning to avoid them is important in maintaining balance. Most dentists report problems with scheduling and practice management.10, 11 Therefore, implementing time management solutions can be critical. Improved organization and planning can prevent scheduling conflicts and reduce workload pressures. Consider updating your office technology (computers, software, scanners, recorders, digital cameras) to reduce your time spent in practice-management busywork. These tools might require some initial investment of time and money, but they can return valuable time to your control.

Occupational stress also can be mitigated through increased flexibility, shared autonomy, and a supportive work environment. Involving other members of your dental team in overall practice management can improve staff attitudes and relieve pressure on you. Efforts to promote team building within your staff through special seminars or organized play days can energize your work environment. Solicit the help of your staff in finding new ways to be efficient and still have fun.

Once you have identified potential sources of stress, try to think creatively about new ways to handle them and meet your goals. Books, seminars, and coursework on managing time, stress, and your dental practice can offer innovative solutions. Eliminating activities in your life that add stress without value can free your time for more fulfilling activities. Giving up something that doesn’t align with your goals can make room for something else. Financial, professional, and personal counselors can provide insights. Tap into your personal network of support for other viewpoints. Taking care of ourselves means that we don’t try to do it all and that we can lean on others for help.

Create balance through volunteerism

Dr. Pankey’s cross of life can be viewed as a lifestyle equilibrium. When properly weighted, the four-sided equilibrium provides for our well-being and leaves us centered and focused. Many health care professionals - including dentists - derive great personal satisfaction from contributing to a patient’s health.15 In fact, this personal satisfaction benefit may offset occupational stress.

Overall, volunteering can be fulfilling. Many women already volunteer their time for support groups and community or school events in addition to formal professional venues. Research has shown that individuals of all ages receive value from volunteering.16 Volunteerism fuels our self-respect, which is an often under-appreciated source of well-being and health.17 It also can expand our experience and skills. Not surprisingly, volunteers report a strong sense of accomplishment, as well as community leadership.

Women dentist professionals have an ability to contribute to volunteer programs that marry our professional and community interests. National American Dental Association programs such as Give Kids a Smile are excellent examples. Through this program and others like it, dentists provide oral health care to thousands of low-income children throughout the country who otherwise could not afford it.

In Arizona, I work as a volunteer for the Neighborhood Christian Clinic, a dental clinic that treats families who otherwise would be unable to afford dental care. Consistent with Dr. Pankey’s philosophy, the clinic provides oral care that emphasizes clinical excellence and also cares for the emotional and physical well-being of each patient. I have found my work there rewarding and satisfying. It also is liberating to focus on caring for others without thinking about profit, overhead, financial reward, or efficiency. I am selfish about these activities: They help me keep myself balanced.

Recently, a young mother was scheduled for routine restorative treatment at the clinic. As we began the procedure and placed the topical, her eyes flooded with tears. This young woman was lonely, abused, and needed our support; her heart was breaking with a pain I could not imagine. We brought the chair up and rescheduled her dental treatment for another day. More important, we spent that scheduled hour providing comfort and care for her as a person, focusing that day on her heart - not her teeth. To provide this type of care is a privilege I never envisioned in dental school - one that brings incredible balance to my cross of life.

Other health care professionals have found creative ways to volunteer with greater impact. As portrayed in Malcolm Galdwell’s “The Tipping Point,” one innovative nurse increased awareness about diabetes and breast cancer by educating community hairstylists. These individuals, in turn, fostered dialogue and communication among their clients - a creative and effective use of an existing but non-traditional community resource.

As part of a creative effort of several families and organizations, my husband, Curt, and I participate in bringing medical and oral health care to a Central American community. We have helped develop a coffee agribusiness project to support their continuing medical, dental, and job needs within the community. Perhaps you also know creative opportunities within your own community (or around the world) for volunteering. Regardless of where you give, the needs are unlimited, and the impact is immeasurable in creating a balanced life.

Say it again

Taking care of ourselves means providing for our emotional, physical, and spiritual well-being. In addition to self-esteem, work stress and job satisfaction have emerged as strong predictors of our perceived health. We can mitigate stress and improve job satisfaction by addressing issues of practice and time management. Prioritizing our lives can help us focus on our values and align goals. Finally, taking time to help others through volunteerism can be a cornerstone of self-esteem and professional satisfaction. Women dentists have many opportunities to contribute to our communities personally and professionally. Together, these elements balance and enrich our lives. We must learn to envision the rewards of healthy living and the synergy of a balanced life. Only then can we fully realize the privilege of giving that is ours to enjoy.

Acknowledgements: The author gratefully acknowledges the contributions of Pamela Rodgers, Ph.D., and Karen Baillie of SmartPractice during the creation and editing of this manuscript.

References

1 Fosdick HE. Finding unfailing resources. In Riverside Sermons. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1958.

2 Okosun IS, Chandra KM, Boev A, Boltri JM, Choi ST, Parish DC et al. Abdominal adiposity in U.S. adults: prevalence and trends, 1960-2000. Prev Med 2004; 39(1):197-206.

3 Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999-2002. JAMA 2004; 291(23):2847-50.

4 CDC. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2001. National Vital Statistics Reports 52[9]. 2004.

5 Koelling TM, Chen RS, Lubwama RN, L’Italien GJ, Eagle KA. The expanding national burden of heart failure in the United States: the influence of heart failure in women. Am Heart J 2004; 147(1):74-8.

6 Rada RE, Johnson-Leong C. Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among dentists. J Am Dent Assoc 2004; 135(6):788-94.

7 Alexander RE. Stress-related suicide by dentists and other health care workers. Fact or folklore? J Am Dent Assoc 2001; 132(6):786-94.

8 Myers HL, Myers LB. ‘It’s difficult being a dentist’: stress and health in the general dental practitioner. Br Dent J 2004; 197(2):89-93.

9 Wells A, Winter PA. Influence of practice and personal characteristics on dental job satisfaction. J Dent Educ 1999; 63(11):805-12.

10 Lawrence A. A study of the work stress and health of GDPs. Br Dent J 2004; 197(2):83.

11 Roth SF, Heo G, Varnhagen C, Major PW. The relationship between occupational stress and job satisfaction in orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2004; 126(1):106-9.

12 Eaker ED, Sullivan LM, Kelly-Hayes M, D’Agostino RB, Sr., Benjamin EJ. Does job strain increase the risk for coronary heart disease or death in men and women? The Framingham Offspring Study. Am J Epidemiol 2004; 159(10):950-8.

13 Asa R. The ‘vision’ thing: success depends on knowing who you are. AGD Impact 2003; 31(1):1-3.

14 Presswood R. A recollection and overview of the philosophy as taught by Dr. L.D. Pankey. Tex Dent J 2002; 119(2):148-50.

15 Roth SF, Heo G, Varnhagen C, Glover KE, Major PW. Job satisfaction among Canadian orthodontists. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003; 123(6):695-700.

16 Thoits PA, Hewitt LN. Volunteer work and well-being. J Health Soc Behav 2001; 42(2):115-31.

17 Rohrer JE, Young R. Self-esteem, stress and self-rated health in family planning clinic patients. BMC Fam Pract 2004; 5(1):11.

Beth R. Hamann, DDS

Dr. Hamann serves as vice president of SmartPractice. She developed Hands of Hope, a Central American dental-medical outreach program. She consults and speaks on issues important to women in dentistry. Contact her at [email protected].