Confessions of a former domestic production activities deduction hater

When I was first introduced to the domestic production activities deduction (DPAD) and its relationship to in-house crown fabrication using CAD/CAM technology, I was not a believer.

The deduction originates in Internal Revenue Code section 199, which was enacted October 22, 2004, as part of the "American Jobs Creation Act of 2004." The opening wording of this Act states that its purpose is to "amend the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 to remove impediments in such Code and make our manufacturing, service, and high-technology business and workers more competitive and productive both at home and abroad."1 Who would not be in favor of that?

As the Act's title suggests, the creation of US jobs was a major objective. To facilitate this, a provision that served as an incentive for companies to employ overseas labor was eliminated; the replacement for the eliminated provision was the DPAD. The plan was not only to discourage overseas activity, but also to promote an increase in US activity. The deduction is equal to 9% of qualified production activities income (QPAI). We will explore this below.

BY JEAN PATTERSON |What's ahead for section 179 expensing and tax reform in 2015?

The root of my skepticism was twofold: First, the Act's application to dentistry seemed inconsistent with its "spirit"-what does in-house crown creation have to do with job creation? It might even be argued that it has the opposite effect: What if external laboratory jobs were reduced?

My second objection, putting aside the first, was that the calculation seemed like an excessive amount of work for a rather small deduction.

My conversion took place as I began to study the text of the Act, the related regulations, and the instructions to the applicable forms. This is what I discovered:

The definition of "manufacturing" within the Act is broad. The related regulations define manufacturing in part as "making qualifying production property . . . from new or raw material by processing, manipulating, refining, or changing the form of an article."1 So maybe now I can believe . . .

While at first glance the calculation appears cumbersome, it does not have to be. The regulations and form instructions note three methods of computing the deduction.

The differences in the methods relate to how expenses are allocated to the domestic production gross receipts (DPGR).

The section 861 method involves allocating expenses to each type of income, and creates "operative sections" of activity. Using this method for dental practices is extremely difficult and unnecessary. It's so difficult and unnecessary that further discussion of this method is beyond the scope of this article.

The small business simplified overall method is the easiest but does not necessarily result in the larger deduction. To be able to use this method, average annual gross receipts must be no more than $5 million, or the practice has to be eligible to use the cash method of accounting. Under this method, total cost of goods sold and other deductions are ratably apportioned between DPGR and non-DPGR based on relative gross receipts.

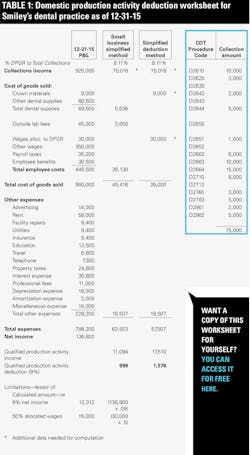

For example, consider the following: A practice has annual collections of $925,000 and total expenses of $788,200 for a net income of $136,800. If DPGR is $75,018 (8.11% of annual collections), then the expenses allocated to the DPGR is $63,923 ($788,200 X .0811). The resulting difference of $11,095 ($75,018 - $63,923) X 9% is the $997 deduction amount.

For this method, all that is needed is the amount of collections from the production activities. This should be easily compiled by combining the amounts for the specific crown-related procedure codes.

READ MORE |Tax diversification – minimize your taxes in retirement from your dental practice

The simplified deduction method is used to allocate other expenses (but not cost of goods sold) based on the ratio of DPGR to non-DPGR. This method is available if business assets are $10 million or less, if or average annual gross receipts are $100 million or less. It is not as straightforward as the small business simplified overall method, but it may result in a higher deduction amount. If the practice from the example above knew the cost of the materials used for crowns and the payroll amount for the employees forming the crowns, then the net becomes $17,510 rather than $11,095 and the deduction increases to $1,576. I show the comparison of the two methods on a worksheet (table 1).

It has been said that the devil is in the details. The details you need to know are that the deduction is limited to the lesser of:

• Computation from whatever method is being used.

• 9% of the unallocated net income for the period. So if the practice has a loss, it is game over.

• 50% of the wages allocated to the production activity.

Other details come into play if the practice operates as an S corporation. In that case, the components pass through to each shareholder and are combined with other such activity, if any, and the result is calculated at the individual level. Also, if there is insufficient basis in the corporation, the deduction is suspended until basis is restored.

READ MORE |5 hidden tax opportunities for dental professionals

Be aware that it may cost more to have the deduction calculated than the tax savings generated. If you are considering the calculation, it might be a good idea to have the discussion with your accountant now-and maybe run some estimates. Be prepared to provide all the information. If you want to segregate the material costs, the time to do that is now-not at year-end. You can add a new account to your general ledger to capture the costs. You can also set up a payroll category to segregate the payroll costs associated with the crown production.

I fully understand that there are those who do not share my newfound faith and I respect their view-but can I still get an Amen?!

References

1. U.S. Congress. H.R. 4520 - American Jobs Creation Act of 2004. Congress.gov. https://www.congress.gov/bill/108th-congress/house-bill/4520/text. Accessed June 1, 2015.