This article first appeared in the newsletter, DE's Breakthrough Clinical with Stacey Simmons, DDS. Subscribe here.

If we want to provide our patients with the most predictable treatment outcomes, then our decisions should always come from an evidence-based point of view. Obviously independent clinical judgment and a well-informed patient will aid in the definitive course of action.

Treatment options

Nonsurgical endodontic retreatment should be our first treatment choice when failing endodontic treatment is noted. There are always four potential courses of action that the patient needs to understand in order to obtain an adequate informed consent:

- Nonsurgical endodontic retreatment

- Apical surgery

- Extraction (with or without replacement)

- No treatment (this choice needs proper documentation)

The course of action taken becomes an easier decision when an apparent etiology can be identified. In my office, I will routinely take a narrow-field CBCT image of the tooth in question to try to diagnose the etiology of the post-treatment disease. Once this is ascertained, the prognosis of the various treatment options can be discussed with the patient. With the ability to sit down and review all of our diagnostic information, the patient is able to make a well-informed decision on the best available treatment options for the case.

The cases presented in this article will show how the aid of CBCT imaging, along with proper case selection, can help us maintain our patient’s natural dentition.

ADDITIONAL READING |Nonsurgical endodontic retreatment with the aid of cone beam (CBCT) imaging

“Traditional apical surgery” versus “microsurgical endodontics”

Apical surgery has lost favor in the treatment planning process due to the poor success of “traditional apical surgery,” Since the advent of the surgical operating microscope, many long-term studies in the endodontic literature have shown success rates higher than 90%. We can obtain this high success rate when a microsurgical treatment approach is taken along with proper case selection. The latter has become a much easier process with the use of CBCT imaging. With the use of three-dimensional imaging, many of these surgical cases that would otherwise have failed due to an untreatable etiology (such as a vertical root fracture) have been eliminated from unnecessary treatment. The patient can be referred for an extraction, as any attempt at apical surgery will ultimately be unsuccessful in such cases.

Several major differences exist between “traditional apical surgery” and the more current “microsurgical endodontics.” Traditional surgery techniques required a large osteotomy, used little or no magnification, required a 45-degree or greater bevel for resection of the root, used round burs for the root-end prep, and amalgam served as the retrograde filling.

ADDITIONAL READING |Endodontic insight: Maximizing canal cleansing with minimal dentinal weakening

The microsurgical approach allows the clinician to keep the osteotomy to a minimum (less then 10 mm), root resection is kept as close to a zero-degree bevel as possible (which decreases the exposed dentinal tubules), and, in turn, decreases bacterial leakage. Ultrasonic instrumentation is used to perform the root -end prep, keeping the prep cleaner and more centered to avoid possible perforation. The current protocol also calls for the use of biocompatible root-end fillings such as MTA, or a bioceramic filling material.

The two cases presented in this article will show that with the use of advanced imaging modalities and a microsurgical approach, we can attain a nice result that allows our patients to keep their natural dentition.

Case No. 1

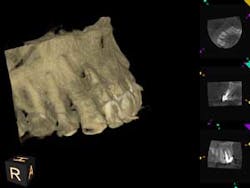

A 60-year-old male patient presented with a buccal swelling in the maxillary left anterior. Clinically the patient had a three-unit bridge connecting Nos. 7–9 (figure 1). The patient was happy with the esthetics and wanted to save his natural dentition. The recommendation was made to take a narrow-field CBCT scan to evaluate No. 7 in three dimensions. The CBCT scan showed that the apical disease had led to root resorption at the apical third of tooth No. 7 on the distal root surface (figure 2). This was invaluable information that allowed me to make the best approach to the root surface while keeping the osteotomy as small as possible. It also allowed me to have a three-dimensional view of No. 7 before even beginning the surgery, which helped to aid in proper root resection to conserve as much sound tooth structure as possible.

After root resection, root end prep and the placement of biologically compatible root end filling, the osteotomy was grafted (figure 3). Because of the size of the apical disease, along with the large cast post and the resorption, traditional nonsurgical retreatment was not a viable option for long-term success. With the aid of the CBCT imaging, it was already noted where the root end filling needed to be placed not only to seal the distal defect but to seal the true apical terminus.

Case No. 2

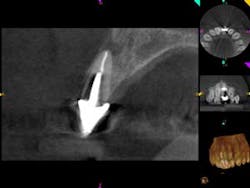

A 52-year-old male patient presented to the office with pain related to tooth No. 9. After radiographic review (figure 4), it was noted that No. 9 had previous endodontic therapy along with a large cast post. The patient was happy with the esthetics of the crown on No. 9, and the clinical and radiographic review showed intact margins and a sound restoration. The recommendation was made to take a narrow-field CBCT image of tooth No. 9. It revealed periapical pathology related to tooth No. 9 that had not broken through the buccal or palatal cortex (figure 5). No fractures were noted and disassembly of the current restoration was not ideal due to the size of the casting in place. The patient was appointed for microsurgical endodontic treatment to save tooth No. 9.

Again, a very minimal osteotomy could be made with the use of an operating microscope. After proper root resection, root-end prep, the placement of a biocompatible bioceramic filling (figure 6), the site is ready to be grafted. The lesion is removed and sent for biopsy, and we are left with a zero-degree bevel to root-end prep, and filling at this point becomes analogous to a Class I restoration. After radiographic verification that we have proper root resection and adequate apical fill, our bone grafting material was placed and final radiographs where taken (figure 7).

Discussion

Both cases presented were ideal for microsurgical endodontics. For both patients, we are dealing with the esthetic zone, which, in turn, has its own challenges for implant treatment planning.

With one consultation and one working visit, the patient is able to maintain the natural dentition with no need for additional surgery. Placement of an appropriate bone graft at the time of the surgery also sets the stage for possible implant placement in the future if the apical surgery were ever to fail. Again, with the right treatment protocol, microsurgical endodontics has shown a greater than 90% long-term success rate. With appropriate case selection, it should always be considered as an alternative treatment to help maintain the patient’s natural dentition.

This article first appeared in the newsletter, DE's Breakthrough Clinical with Stacey Simmons, DDS. Subscribe here.