Fluoride: What’s new, what’s not, and what do dental patients need to know?

Fluoride is often called nature’s cavity fighter and for good reason. Fluoride, a naturally occurring mineral, helps prevent cavities in children and adults by making the outer surface of their teeth more resistant to the acid attacks that cause tooth decay. Fluoride has been a controversial topic for many years, but people often don’t have the facts and understanding on which to base their decisions.

Fluoride’s origin

The fluoride ion comes from the element fluorine. Fluorine is an abundant element in the earth’s crust in the form of the fluoride ion. Fluoride ions necessary for remineralization are provided by fluoridated water as well as various fluoride products such as toothpaste.

There are three basic additives used to fluoridate water in the United States1,2:

- Sodium fluoride—a white, odorless material available either as a powder or crystals

- Sodium fluorosilicate—a white or yellow-white, odorless crystalline material

- Fluorosilicic acid—a white to off-white colored liquid

Before teeth break through the gums, the fluoride taken in from foods, drinks, and dietary supplements strengthens tooth enamel, making it easier to resist tooth decay and providing a systemic benefit.

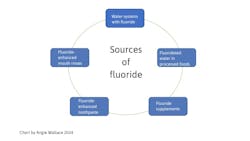

Sources of fluoride

Fluoride can come from various sources (figure 1). In fluoridated cities, fluoride found in commercially processed foods and drinks can contain higher levels of fluoride than those processed in nonfluoridated communities. In addition, the fluoride taken in from foods and drinks continues to provide a topical benefit as it becomes part of the saliva, constantly bathing the teeth with tiny amounts of fluoride that help rebuild weakened tooth enamel.

Topically applied fluoride provides local protection on the tooth surface. Topical fluorides include toothpastes, mouth rinses, and professionally applied fluoride foams, gels, varnishes, and rinses. Systemic fluorides also provide topical protection.

Fluoride from the air/atmosphere normally contains very small concentrations of airborne fluorides. Studies reporting the levels of fluoride in air in the United States suggest that ambient fluoride contributes little to a person’s overall fluoride intake.3

Fluoride from water in the US, the natural level of fluoride in ground water, varies from very low levels to over 4 ppm. Fluoride is naturally found in most all water sources, rivers, lakes, water wells, and even the oceans. For the past 80-plus years, fluoride has been added to public water supplies to bring fluoride levels up to the amount necessary to help prevent tooth decay.

Research about fluoride

Before water fluoridation, children had about three times or more cavities.4 Because of the important role fluoride has played in the reduction of tooth decay, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has named community water fluoridation as one of the 10 great public health achievements of the 20th century.1 Studies prove water fluoridation continues to help prevent tooth decay by at least 30% in children and adults, even with fluoride available from other sources, such as toothpaste and fluoride rinses. Today, at least 75% of the US population is served by fluoridated community water systems.5

After teeth erupt, fluoride helps remineralize and rebuild weakened tooth enamel and reverses early signs of tooth decay. Brushing teeth with fluoride toothpaste or rinsing with other fluoride dental products applies fluoride to the surface of the teeth, offering a topical benefit.

Also by the author … Your guide to using dental lasers in your hygiene practice

Tooth decay and the importance of fluoride

Tooth decay is caused by dental plaque, a deposit of bacteria that constantly forms on teeth. When sugar and other carbohydrates are eaten, the bacteria in plaque produce acids that attack the tooth’s enamel. After repeated attacks, the enamel breaks down and a cavity is formed. Several factors can increase an individual’s risk for dental decay, making patient education even more important.

Dental decay is, by far, the most common and costly oral health problem in all age groups of patients.6 It is one of the main causes of tooth loss from early childhood through middle age. Decay continues to be a major issue for middle-aged and older adults, particularly in the form of root decay due to receding gums. Studies have shown that the availability of topical fluoride in an adult’s mouth during the initial formation of decay not only can stop the decay process but also make the enamel surface more resistant to future acid attacks.7 In addition to gum recession, older adults often experience decreased salivary flow, or xerostomia, due to the use of medications or the presence of medical conditions.

Toothpastes with fluoride have been responsible for a significant drop in cavities since 1960.8To make sure that people have toothpaste with fluoride, toothpastes approved by the American Dental Association have the ADA Seal of Acceptance.

Oral health guidelines for children

Guidelines to help keep children’s teeth healthy include brushing at least twice a day in the morning after breakfast is consumed and at night right before bedtime. Parents should always supervise their children when brushing to make sure they’re using the correct amount of toothpaste and that they are old enough to be able to spit out the toothpaste. If the child is younger than 3, the parent or guardian should start brushing their teeth with a fluoride toothpaste as soon as teeth appear in the mouth. Use only a tiny amount of toothpaste since young children will swallow some.

Before teeth have erupted, parents can use a washcloth wet with water to remove any traces of plaque, which will also allow some fluoride to be placed topically. For children older than 3, increase fluoride toothpaste to a pea-sized amount. Mouthwash with fluoride can help make teeth more resistant to decay, but children aged 6 or younger should only use it if it’s been recommended by a dentist. Children younger than 6 are more likely to swallow toothpaste than spit it out because their swallowing reflexes aren’t fully developed.

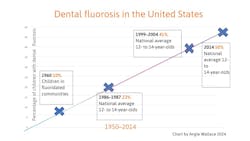

A concern for some is dental fluorosis (figure 2), which is caused by a disruption in enamel formation during tooth development in early childhood and is related to a higher-than-optimal intake of fluoride. After tooth enamel is completely formed, dental fluorosis cannot develop even if excessive fluoride is consumed or ingested.

Fluoride supplementation

For people living in areas where there is no fluoride or less than the suggested amount, there are other options to consider such as fluoride supplements, which are available by prescription only. Fluoride supplements come in tablet, drop, or lozenge form and are recommended for children ages 6 months to 16 years old who live in areas without the recommended amounts of fluoride in their drinking water and who are at high risk of developing cavities. If a child lives in an area with fluoridated water, supplements are not necessary. For children with a high risk for cavities, another option is to visit their dentist for a professional application. Fluoride can be applied directly to the teeth with a varnish, gel, foam, or rinse during the dental visit.

Community fluoridation

The ADA first adopted a policy recommending community water fluoridation in 1950. It has continued to reaffirm its position in support for water fluoridation and strongly urges that the benefits of fluoride be extended to communities served by public water systems.9

Many individuals live in areas with either too much fluoride or not enough fluoride in their water. The Department of Health and Human Services and the US Public Health Service have recommended an optimal level of fluoride in community water systems. The agency’s recommended ratio of fluoride to water has been determined to be at 0.7 parts per million. This is based on 70-plus years of scientific research and analysis for the optimal levels of fluoride received from all sources, including community water.10

Tooth decay can be reduced safely and effectively by at least 25% in both children and adults simply by having it added to drinking water. Fluoridation is the most effective public health measure to prevent dental decay for children and adults, reduce oral health disparities, and improve oral health over a lifetime, and continues to be effective in reducing dental decay by 20%–40%.11

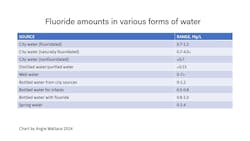

According to data compiled by the ADA and the CDC Division of Oral Health as of May 2005, 42 of the 50 largest cities in the US are supplied with fluoridated water.12 Fluoride levels vary in different forms of water (figure 3).

Where does bottled water fit in?

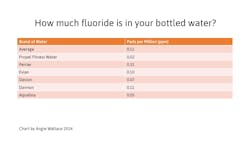

Individuals who drink bottled water as their primary source of water could be missing the decay- preventive effects of optimally fluoridated water available from their community water supply. The fluoride content of bottled water can vary greatly, and there are also many kinds of home water treatment systems including water filters, reverse-osmosis systems, distillation units, and water softeners. Individuals who consume water from these sources are at a higher risk for decay.13 We must educate patients since most are unaware that fluoride has been removed from these products.

Fluoride and the body

Every day, the body takes in fluoride and loses fluoride. The way you take in fluoride is through foods you eat and water you drink. The way you lose fluoride is through demineralization of the teeth when acids caused by plaque bacteria and sugars in the mouth attack tooth enamel. You can "put fluoride back" (as well as calcium and phosphate) into your tooth’s enamel layer by eating healthy foods and drinking fluoridated water (figure 4). Basically, if patients lose fluoride faster than they take it in, they will be at risk of tooth decay.

Fluoride’s effects on oral-systemic health

Oral health affects the quality of one’s life and general health. Good oral health lowers one’s risk of things such as:

- Periodontal disease

- Tooth decay

- Tooth loss

- Oral and throat cancer

- Facial and mouth pain

- Oral sores and infection

- Other disorders and diseases that can limit the capacity to chew, bite, speak, smile, and have psychosocial well-being

Patients have an increased risk for oral diseases with tobacco and alcohol use, as well as unhealthy diets. Chronic diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases can also increase the risk of oral diseases. This is also the case with poor oral hygiene.

Dental products that can help

Many products are available that can help rebuild areas exposed to decay, including foams, rinses, and gels. Fluoride varnish is a dental treatment that can help prevent tooth decay, slow it down, or stop it from getting worse. It is made with fluoride, a mineral that can strengthen tooth enamel. Fluoride varnish treatment typically comes as a saline or salt preparation in a resin or alcohol-based solution that’s fast-drying.

Each manufacturer varies in how they dispense this fluoride concentration. Although 5% is the typical sodium fluoride concentration, others contain only 1%–2.5%. Some come in a polyurethane base, while others come in a shellac base. Keep in mind that fluoride varnish treatments cannot completely prevent cavities. Fluoride varnish treatments can help prevent decay, remineralize teeth, eliminate sensitivity, and destroy bacteria that can cause periodontal disease. These benefits—along with brushing with the right amount of fluoride toothpaste, flossing regularly, getting regular dental care, and eating a healthy diet—are all part of maintaining oral health.

Adult patients can also benefit from fluoride varnish treatments, perhaps even more so than children. If patients display the following characteristics, they may be good candidates for fluoride varnish treatment:

- Have sensitive teeth

- Have periodontal disease

- Have frequent tooth decay

- Have exposed tooth roots and gum recession that leave them vulnerable to decay

- Don’t brush or floss frequently

- Have a dry mouth

- Drink soda frequently or other acidic drinks

- Have multiple fillings or crowns

- Have teeth with developmental defects or deep pits and grooves

- Have braces or retainers that can trap plaque in or around them

Silver diamine fluoride

Silver diamine fluoride (SDF) has caught everyone's attention lately. Here's what you need to know about incorporating it into your dental practice.

Commercially available as Advantage Arrest by Elevate Oral Care, 38% SDF is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the reduction of dentinal hypersensitivity. It has also been shown to reduce bacteria and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are responsible for the degradation of dentin, and it is believed to arrest carious lesions.14

SDF will only stain defects in the tooth structure, such as carious lesions and restorative margins. Sound tooth structure will not be stained. SDF is also cost-effective as one drop can be used for multiple teeth.

SDF will stain carious tooth structure a dark brown or black color. Caution should be used on other tooth surfaces and near the margins of composite restorations or crowns. Explain the risks of discoloration to tooth structure to patients before application of SDF. If a restoration is stained, the stain should polish off, but staining around margins may remain.

Educating yourself on the risks and benefits before using SDF will be helpful so that the application process is smooth.14

Patients who can benefit from fluoride treatments

Some patients have conditions that put them at increased risk of tooth decay, so additional fluoride treatments and toothpastes with higher levels of fluoride can be beneficial:

- Dry-mouth conditions caused by diseases or medications. The lack of saliva makes it harder for food particles to be washed away and acids to be neutralized, putting teeth at risk of demineralization. When patients don’t have enough saliva, they may find it difficult to wash away food particles and neutralize acids, which increases their risk of tooth demineralization.

- Gum recession can expose the teeth and roots to bacteria, increasing the chance of tooth decay. Gum recession is common and increases as patients get older, and it can also contribute to dentinal hypersensitivity. About one-third of the 78 million adults in the US who are 60 years old or older are at risk of tooth recession.15 Since dentinal hypersensitivity is more common in this demographic, treating hypersensitivity is imperative. What’s more, since fluoride varnishes are known for treating hypersensitivity, it is often used in gingival recession cases.

- Periodontal disease is a condition where the gums and tissues that surround them are infected. Plaque buildup under and along the gumline can lead to gum disease. There are two types of periodontal disease. Gingivitis is a milder form that good oral hygiene can reverse. With gingivitis, the gums become swollen, red, and may bleed easily. Periodontitis is a more serious type of gum disease that damages the bone and soft tissues that support the teeth. The infected gums form pockets and pull away from the teeth. As the plaque begins spreading, the body’s immune system (as well as help from dental professionals) can help fight the bacteria. This process, along with the bacterial toxins, can break down the connective tissue and bone that hold the teeth in place. If left untreated, the gums, bones, and tissue can become damaged, leading to loose teeth and the need for extractions.

- History of frequent cavities.If your patient has one cavity every year or every other year, they may benefit from additional fluoride. The ADA Council on Scientific Affairs assembled a group of scientists in 2005 to produce scientific evidence to evaluate and back up how effective fluoride is in preventing caries. That same year, the Journal of the American Dental Association published the scientists’ recommendations that supported fluoride varnish treatments for people who are at a higher risk for caries.16 If your patients eat a lot of sugary foods, are frequent snackers, or have a family history of caries, they are at greater risk of tooth decay and could benefit from periodic fluoride varnish treatments.

- Dental work (such as crowns, bridges, or braces). Some dental treatments put teeth at risk for decay at the point where the crown meets the underlying tooth structure or around the brackets of orthodontic appliances. Braces, retainers, bridges, crowns, or other dental work can increase the risk of tooth decay.

- Deep pits and groovesin teeth are prone to dental decay.

- Fluoride varnishes are approved through the ADA for dental hypersensitivity.17 Sensitivity occurs when fluids cause pain and nerve pressure due to open dentinal tubules. Fluoride varnish forms a calcium layer that prevents fluid flow by blocking the tubules.

Since varnish can stay on the tooth surface for several hours, it has an advantage over rinses, gels, pastes, and foams. Varnish treatments are ideal for patients experiencing sensitivity to dental products such as whitening treatments. If sensitivity occurs after dental procedures such as scaling and root planing, fluoride varnish can help to reduce the hypersensitivity.18,19

Side effects of fluoride treatments

When used properly, most experts claim that fluoride treatments don’t present many side effects or, if any, they’re typically mild and rare. Because of the adherence and color of varnishes, there might be a slight, but temporary, change in tooth coloration. However, as eating and toothbrushing occurs, the varnish slowly wears away and the yellowish color fades. Patients should avoid drinking hot liquids, such as coffee, tea, or hot soup, and refrain from drinking alcohol, chewing gum, or brushing and flossing their teeth for six hours. This will allow the fluoride to sink into the tooth structure.

Potential side effects (although rare) of fluoride varnish may include:

- White spots on teeth

- Vomiting, nausea, or abdominal pain

- Allergic rashes

- Mouth sores

Patients may experience more serious side effects, such as gastrointestinal bleeding or bone problems. These are extremely rare, however, and typically only occur when patients are exposed to higher doses of fluoride for an extended time. Despite these rare side effects, fluoride is supported by many public health agencies for its benefits to oral health.20

Patient education is key

Topical fluoride varnish application should be part of the dental professional’s entire preventive care routine that involves education on maximizing toothbrushing benefits, professional interventions, and dietary control. Explain to patients that fluoride varnish treatments use a stronger concentration of fluoride than what is found in everyday toothpastes, mouthwashes, and over-the-counter products.

Fluoride varnish treatment typically takes a few minutes and is applied with a brush or cotton swab. The varnish is left on the teeth several hours, allowing it to release fluoride into the cervical and interproximal areas where fluoride is needed the most. If patients continue to experience dentinal sensitivity, advise them to come in every six months for a reapplication.21,22

With all the information about fluoride, it’s important that patients understand why we are recommending it for their dental care. Take the time to answer their questions and place flyers and brochures in your reception area to help them understand why fluoride is an important part of dentistry.

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in Clinical Insights newsletter, a publication of the Endeavor Business Media Dental Group. Read more articles and subscribe.

More about fluoride from DentistryIQ ...

References

- Ten great public health achievements–United States, 1990-1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR. 1999;48(12):241-243.

- 60th anniversary of community water fluoridation. American Dental Association. January 24, 2005. https://www.newswise.com/articles/60th-anniversary-of-community-water-fluoridation

- Questions and answers on fluoride. United States Environmental Protection Agency. January 2011. Accessed November 15, 2022. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-10/documents/2011_fluoride_questionsanswers.pdf

- Yiamouyiannis JA. Water fluoridation and tooth decay: results from the 1986-1987 National Survey of U.S. Schoolchildren. Fluoride. 1990;23(2):55-67.

- Water fluoridation data and statistics. Division of Oral Health. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reviewed June 9, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/fluoridation/statistics/index.htm

- Griffin SO, Regnier E, Griffin PM, Huntley V. Effectiveness of fluoride in preventing caries in adults. J Dent Res. 2007;86(5):410-415. doi:10.1177/154405910708600504

- Fluoride in water. American Dental Association. https://www.ada.org/resources/community-initiatives/fluoride-in-water

- How fluoride helps to prevent tooth decay. MouthHealthy. American Dental Association. http://www.mouthhealthy.org/en/az-topics/f/fluoride

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Federal Panel on Community Water Fluoridation. U.S. Public Health Service recommendation for fluoride concentration in drinking water for the prevention of dental caries. Public Health Rep. 2015;130(4):318-331. doi:10.1177/003335491513000408

- Horowitz HS. The effectiveness of community water fluoridation in the United States. J Public Health Dent. 1996;56(5 Spec no):253-258. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.1996.tb02448.x

- McDonagh MS, Whiting PF, Wilson PM, Sutton AJ, et al. Systematic review of water fluoridation. BMJ. 2000;321(7265):855-859. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7265.855

- Community water fluoridation in the United States. Policy Number: 20087. American Public Health Association. October 28, 2008. Accessed August 23, 2017. https://www.apha.org/Policies-and-Advocacy/Public-Health-Policy-Statements/Policy-Database/2014/07/24/13/36/Community-Water-Fluoridation-in-the-United-States

- Kant AK, Graubard BI, Atchison EA. Intakes of plain water, moisture in foods and beverages, and total water in the adult US population—nutritional, meal pattern, and body weight correlates: National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 1999–2006. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(3):655-663. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.27749

- Advantage Arrest silver diamine fluoride 38%. Elevate Oral Care. https://www.elevateoralcare.com/products/AdvantageArrest

- Featherstone JDB, Horst JA. Fresh approach to caries arrest in adults. Decisions in Dentistry. October 5, 2015. http://decisionsindentistry.com/article/fresh-approach-to-caries-arrest-in-adults/

- Koulourides T. Summary of session II: fluoride and the caries process. J Dent Res. 1990;69(2 Suppl):558. doi:10.1177/00220345900690S111

- Fontana M, Young DA, Wolff MS. Evidence-based caries, risk assessment, and treatment. Dent Clin N Am. 2009:53(1):149-161. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2008.10.003

- Stookey GK. Review of fluorosis risk of self-applied topical fluorides: dentifrices, mouthrinses and gels. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1994;22(3):181-186. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.1994.tb01837.x

- Oral health in America: a report of the surgeon general. US Department of Health and Human Services. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. National Institutes of Health. 2000. https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2017-10/hck1ocv.%40www.surgeon.fullrpt.pdf

- Mariri BP, Levy SM, Warren JJ, Bergus GR, Marshall TA, Broffitt B. Medically administered antibiotics, dietary habits, fluoride intake and dental caries experience in the primary dentition. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(1):40-51. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0528.2003.00019.x

- Dean HT. Chronic endemic dental fluorosis. JAMA. 1936;107(16):1269-1273.

- Kumar JV, Swango PA, Opima PN, Green EL. Dean’s fluorosis index: an assessment of examiner reliability. J Public Health Dent. 2000;60(1):57-59. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.2000.tb03294.x

Angie Wallace, RDH, has been a clinical hygienist for over 35 years. She obtained her advanced level proficiency in the Academy of Laser Dentistry and is the only dental hygienist in the organization to have educator status, the ALD Recognized Course Provider designation, and a mastership. She is chair of the ALD education committee, regulatory affairs committee (working with states on dental hygiene laser use), and auxiliary committee. In 2023, she received the ALD Educator of the Year Award and the ADHA Entrepreneur of the Year Award. She is an international speaker, has published a book about dental hygiene and lasers, and is an in-office laser consultant with her laser education company, Laser Hygiene, LLC. Contact her at [email protected].

About the Author

Angie Wallace, RDH

Angie Wallace, RDH, has been a clinical hygienist for more than 35 years. She is a member of the Academy of Laser Dentistry (ALD), where she obtained her advanced level proficiency, educator status, Recognized Course Provider status, and mastership. Angie is the chair for education on the ALD Board of Directors and serves on both the Regulatory Affairs and Auxiliary committees. She has a laser education consulting company, Laser Hygiene, LLC, and has been recognized as a worldwide speaker. Contact her at [email protected].