It never fails. It’s 4:30 on Friday afternoon, and you have a patient complaining of pain “here” (he points to the entire left side of his face) that occurs “sometimes with hot, sometimes with cold and chewing.” What a diagnostic nightmare!

What is the right protocol: prescribe narcotics and antibiotics and send him on his way? Open the tooth? Wonder why you didn’t become an orthodontist so you could avoid these conundrums?

Diagnosis of endodontic problems can be a challenging part of the treatment process. It can frustrate clinicians and patients. Part of the difficulty is that it is not always a black-and-white issue; there are many shades of gray, including subtle nuances in the patient’s history that must be addressed when making treatment decisions.

Diagnostic classification

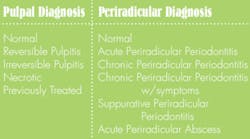

Prior to performing any endodontic procedure, it is crucial to establish pulpal and periradicular diagnoses. The following diagnostic classification is most commonly accepted by the American Association of Endodontists. (These diagnostic terms vary, and the accepted terminology is fluid. Other similar diagnostic terms may be acceptable.)

For clarification, the acute classifications refer to recent symptomatology. The chronic classifications refer to a situation that is longer-standing and can be viewed on a radiograph. Suppurative Periradicular Periodontitis is used when a sinus tract or drainage area is present. An Acute Periradicular Abscess occurs when there is acute swelling, pus formation, tenderness, and eventual swelling with or without radiographic pathology.

Identification of a coronal or radicular fracture is also important. Although this is not specifically a pulpal or periradicular diagnosis, it is important to note because fractures may greatly change your proposed treatment plan. TMJ dysfunctions may also present as dental pain, so keep in mind the clinical presentation of patients with those symptoms as well.

History of chief complaint

The most important first step in establishing a diagnosis is a thorough history of symptoms because many things patients tell you are important for reaching a diagnosis. Questions you should ask include:

- Can you localize the discomfort?

- Have you noticed any swelling, and if so, where?

- Is there a current or past sensitivity to temperature? If so, describe it.

- Have you needed to take pain medication for this tooth? Have you taken any antibiotics?

- Is the discomfort worse in the morning?

- Have you experienced muscle pain in your face, neck, or both?

- Is the discomfort spontaneous?

- Have you had any sinus problems lately?

- Are you sensitive to chewing or pressure?

- Does the discomfort wake you at night?

- Have you had any recent dental work?

- How long has the crown been in place?

- Do you clench or grind your teeth or chew ice?

It is important to recreate the patient’s chief complaint during your clinical examination.Most dentists have a specific sequence of tests they perform. This reduces the chance you will miss an important piece of evidence. Make every effort to recreate the stimuli that elicit the patient’s chief complaint. Also note that antibiotics and pain medications can make the diagnostic process more challenging and less reliable.

Clinical evaluation

The clinical evaluation consists of several basic tests, palpation, percussion, periodontal probing, thermal/electrical testing, and biting and release. For completeness, all tests should be performed on the tooth in question and the adjacent teeth as well. Testing the contralateral side or the opposite arch on the ipsilateral side can also be helpful in establishing a diagnosis.

Palpation, percussion, periodontal probing

The first step in the examination is to perform a visual evaluation by looking at the patient straight on to discern if there is any visible swelling or asymmetry. Both extraoral and intraoral digital palpation should be performed, including the lymph nodes on the affected side. Be sure to palpate the buccal and lingual/palatal surfaces and ask the patient if the areas are sensitive.

Percussion should be performed with the utmost care, especially in patients who have the chief complaint of biting, chewing, or pressure sensitivity. Using a finger, “Tooth Slooth” or other plastic instrument may elicit symptoms without the discomfort of the handle of a metal instrument. Start gently and increase the intensity slowly. Testing the adjacent teeth first is a good way to gauge the patient’s reaction. If he responds strongly with a healthy tooth, be extra gentle when testing the tooth in question. Using your fingertip is enough for some patients.

Periodontal probing is important, especially in diagnosis of suspected root fractures or combined periodontic-endodontic problems. Performing line angle, mid-buccal and mid-lingual measurements around the tooth in question and those adjacent should not be omitted. During this portion of the evaluation, examine the gingiva for inflammation and exudate.

If a sinus tract is present, trace it. This is a general rule and crucial in patients who may have multiple affected teeth. Using a small gutta-percha point and gentle pressure is usually tolerable. Take a radiograph with the point in place and show the patient how it acts like an arrow directing you to the root of the problem (no pun intended).

Thermal and electrical tests

The pulpal diagnosis is obtained by using thermal or electrical tests. Thermal tests may be hot or cold, depending on the chief complaint. There are several ways to reproduce the sensation of cold. These include a skin refrigerant (such as Endo Ice®), ice pellets, or a CO2 stick.

The most effective method, especially through full-coverage restorations, is the CO2 stick. This requires a tank of liquid CO2, which may not be feasible.

The skin refrigerant is the next-best thing. It is important to maximize the cold sensation. It is recommended that you test the tooth by spraying a fluffed cotton pellet held in a metal forceps and placing it on the buccal surface.

The most effective way to heat-test teeth is to isolate each tooth using a rubber dam and flood the area with water that approximates the temperature of a warm or hot beverage. Warn the patient that there will be some pressure, but anesthetizing defeats the purpose.Heat testing should never be performed with a melted stick of wax or an electrically or flame-heated instrument. This type of heat is difficult to control and may cause pulpal damage in healthy teeth.

As soon as the patient feels any type of sensation, remove the stimulus and ask him to report his feelings: Is the sensation painful? Does it linger? Is this what he feels when he drinks or eats something hot or cold?

The electrical pulp test is helpful when natural tooth structure is available and the results of the thermal tests are inconclusive. The EPT cannot be used on restorations and is not reliable when placed too close to the gingiva. Ideally, the area should be isolated and the tooth dry. Conducting medium, such as topical anesthetic or toothpaste, should be used and the patient instructed to raise a hand as soon as any sensation is felt. Testing a normal tooth first is good to give the patient a baseline of what the test feels like, even if it is not an adjacent tooth.

Although the results are given numerically, usually from a scale of one to 80, it is impossible to know how “alive” the tooth is. A response before the scale is at its maximum means that there is some vital tissue inside the tooth; no response at the maximum number means that there is not.

Biting and release

This test is useful for several things, including the diagnosis of a coronal fracture. It is best to have a Tooth Slooth for testing cusps individually. Another item that aids in diagnosis is a burlew wheel, which has some elasticity and may mimic chewing. When using the Slooth, ask the patient to bite down, squeeze his teeth together, and open quickly. Explain each step to him before you start, and instruct him to note if the pain is upon biting or release. Pain upon release from biting with the absence of any other symptoms and normal responses to the other diagnostic tests is frequently correlated to a coronal fracture. This is usually effectively treated with a full-coverage restoration.

Radiographic evaluation

The clinical evaluation is the most important part of the diagnostic process because there is often a lack of radiographic pathology associated with an endodontic problem. To view radiographic bone destruction, there must be erosion of one of the cortical plates. There can be extensive loss of cancellous bone without any radiographic pathology.

There are also shades of gray with a normal periodontal ligament vs. a widened periodontal ligament, etc. The easiest diagnosis in this case is “Yes, there is a periradicular radiolucency, the pulp is necrotic, and you do need endodontic therapy.” Look for the J-shaped lesion, which might indicate a root fracture. Angled films are also crucial to obtain a diagnosis, as well as verification of the presence of additional roots and or canals, and determining anatomical variations.

Conclusions

Endodontic diagnosis can be challenging.

Understanding both the pulpal and periradicular diagnoses and how to obtain them are crucial. Although it can be frustrating for the patient and the provider, sometimes no treatment until the symptoms localize is the best option. It is a better alternative than choosing to perform treatment on tooth 19 and then determining several days later that tooth 18 was the true culprit. Patients will appreciate your honesty and desire to find the true etiology of their discomfort.

References

- American Board of Endodontics: Glossary of Endodontic Terms.

- Bender IB, Seltzer S: Roentgenographic and direct observation of experimental lesions in bone parts I and II, 1961.

- Cohen S, Burns RC: Eds. Pathways of the Pulp. 6th ed. St Louis: Mosby, 1994:21-23.

- Cohen S, Burns RC: Eds. Pathways of the Pulp. 7th ed. St Louis: Mosby, 1998:1-19.

- Kelly WH, Ellinger RF: Pulpal-periradicular pathosis causing sinus tract formation through the periodontal ligament of adjacent teeth. JOE May;14(5)251-257.

- Montgomery S, Ferguson CD: Endodontics: diagnostic, treatment planning, and prognostic considerations. Dent Clin North Am 1986;30:333-348.