The next-generation note: Computerizing patient-centered information for the modern dental practice using C Notes

Next-generation apps can accelerate dentistry’s adoption of health information technologies

There is reason, however, to believe that this can—and will—change. With the advent of next-generation dental technologies, including apps, dentists can hope to find improved platforms that give them the thoroughness and ease-of-use they are looking for. In this article, we will look at some of the obstacles facing dentistry in this area. We will also look at Centric Notes (C Notes), a program that aims to bridge the gap between dental clinical practice and health information technology.

Background

In 2006, Schleyer et. al found that 90% of dentists in the United States use one or more computer in their practices.2 While that number has likely increased, it does not mean that the recording clinical information is solely computer-based. In 2013, Schleyer et. al found that approximately 75% of dentists use computers to manage some kind, but not all, of their patients’ clinical information.3

Dentists desire dental computing to have patient-centered elements, such as writing clinical notes, recording diagnoses, and outlining treatments, in a manner that is just like a paper chart.2 Dentists, it seems, do not want to remain technologically “backwards” and work within the confines of a paper chart, but they would like to digitize patient-centered clinical information in a way that allows a relational use of the data. The information and recording methods of the paper chart, after all, have been used for more than half a century—they are battle tested.

Next-generation apps and electronic dental records (EDRs)

The creation of next-generation computer applications for dentistry requires new thinking and new approaches based on a tried and true clinical framework and cognitive engineering methods. The ability to record clinical data and be able to relationally apply it to patient care can potentially increase workflow efficiency.

Electronic dental records (EDRs) can be powerful instruments when used in a patient-centered setting. Adopting an EDR in a clinical setting requires a profound change in the way a dental office captures patient data with technology, but it can be done.4,5

Interestingly, a 2009 Harvard Medical Study concluded that computerized medical records are not improving medical efficiency and quality of care. The reason was a disconnect between the practice management uses of the computerized records and the doctors' clinical needs. According to the study, “Practice management software is designed to primarily handle billing, accounting, and registration needs, but not clinical needs.”6

Analysis from The Center for Dental Informatics shows that today’s EDRs do not effectively mirror the information found in paper charts. The primary reason is that practice management software (PM software) stops at the clinical interface. It was found that PM software is built on accounting principles and not patient-centered operations such as writing clinical notes, recording diagnosis, and documenting treatments like the paper chart. 7

In 2010, Larry Emmott contended in the Journal of the American College of Dentists that EDRs offer fantastic benefits by saving both time and money, but they have to be fully implemented with historical records kept only on paper.8 He, too, recognized the limits of PM software at the clinical interface.

The mix of digital and paper records

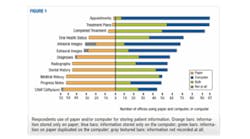

Although moving in the direction to digitization, most dental practices store patient information with a mix of paper and digital media. For example, in 2007 Schleyer et. al found that more than 40% of practices exclusively record on paper the patient's chief complaint, progress notes, medical history, dental history, radiographs, and diagnoses.4

Information commonly associated with accounting, billing, and managerial operations tends to be most frequently stored on computers. Digital radiography, digital photography, and intraoral charting are next in frequency. Information that is stored least frequently on a computer include the medical and dental history, treatment notes, and the chief complaint.7

This least-stored clinical patient information is the substance of relational information that dentists need so they can provide excellent patient care. However, entering patient clinical data is an arduous task. Advanced techniques for data entry are virtually nonexistent, being mostly limited to the dentist manually typing in relevant information.

The legal dangers of templates

Current PM software’s answer to incorporating treatment notes, chief complaints, reasons for visits, and medical histories is to build an adjunct library of templates. Unfortunately, template data entry has problems. One of these problems involves dentists' malpractice liability. Statistics show that a dentist will contend with 3–5 legal issues over the course of a career.9 For dentists, treatment notes are the first line of defense to malpractice claims. However, treatment notes often fall short. According to dental malpractice defense attorney Jeff Tonner, “More times than not the dental chart fails the dentist, not the other way around.” 9

Tonner says this often occurs is because the PM software’s template notes are simply inadequate. Writing using a template raises serious ethical issues with regards to credibility of the written note, accuracy of the note, and the propagation of errors within the note. Template writing is a primary question in legal depositions that affect the doctor’s credibility in legal disputes. On the integrity of the patient chart, Robert MacKenzie, a leading malpractice attorney, says, “If well maintained, the chart should constitute the strength of your case, not the weakness.”10

As discussed above, today’s patient chart is a mix of paper and digital media. This creates further instability in litigious encounters. Maintaining patient information in two places or more has drawbacks. It can lead to incomplete diagnosis, clinical errors, or incomplete treatment plans. This, in turn, can lead to loss of insurance reimbursement and legal complications. Don Morse, DDS, PhD, a legal defense consultant, says, “One of the major causes of malpractice suits is poor or incomplete treatment notes.”11

Record duplication

When asked about inadvertent record duplication, several practitioners who participated in a Center for Dental Informatics study indicated that they were in a period of transition.12 Some practitioners said the EDR system they used was not able to store all information that they wanted to store on their computer system; therefore, the information remained confined to paper.

The Center for Dental Informatics identified several barriers and opportunities for improvement in EDRs.12 Respondents of the study felt EDR software was not easy to use and had limited functionality. Major barriers to EDR implementation were insufficient operational reliability and program limitations. Cost and the learning curve were also seen as barriers for EDR use. “Any technology has the potential to disrupt the practice workflow,” says Schleyer. “The challenge for dental practitioners is to figure out how to implement the technology while not losing too much efficiency and effectiveness in the short term, and realizing the gains that they expect in the long term.”12

Standardization and the baseline dental record (BDR)

No standard exists for the content of dental records. To address this issue, Schleyer and the Center for Dental Informatics created a Baseline Dental Record (BDR). The BDR is a superset of items that should exist in some form in the clinical dental record. As seen in Figure 2, The Center for Dental Informatics BDR contains 21 information categories.

Figure 2: A comparison of information contained in a baseline dental record (BDR), practice management software (PMS), and paper charts.

Most categories of information, such as "chief complaint," "medication history," "hard tissue and periodontal chart," and "radiographic history and findings," are related to obtaining clinical data necessary to determine the patient’s oral health status. Categories such as "systemic diagnoses," "dental diagnoses," and "problem list" each serve to describe the patient’s current oral health status, while “treatment plan” is used to represent the necessary treatment. “Progress notes” and “prescriptions” document care that is delivered.

Several fields that occur frequently in paper records, such as the chief complaint, a list of current medications, allergies, and physician information, tend to be poorly represented in EDRs. In sum, today’s EDRs do not mirror the information content of paper records very well.5,13 When considering EDRs, practitioners should consider systems based on their BDR requirements, usability, ease of use, efficiency, and synthesis of critical patient information.

The promise of technology

When the right combination of technology is strategically placed in the dental practice, it can enhance the office’s performance as well as the level of care it provides. According to Roger Levin, DDS, CEO of the Levin Group, technology does one of two things: it either replaces an existing function at possibly a more efficient level or it brings in a new function.14 Either way, he says, clinicians need to consider the technology as a tool—one of a series of steps in any practice system. Levin explains, “Practices should have their systems in place and then identify where the technology fits, how it will be used, who will use it, whether its use will be a reimbursable service.”14

Incorporating more BDR categories into EDRs to better mimic the paper chart will allow practitioners to get closer to fully implementing a complete EDR in their practice. In digital dentistry, not all technology will be supplied by one company. This increases the importance of standards that allow products of different suppliers to work together properly.

C Notes

C Notes is a note-generating app that helps to balance the EDR to BDR ratio of popular dental software systems. The C Notes app runs on an iPad and allows practitioners to more appropriately mimic a complete dental paper chart by digitally generating patient-centered treatment information without having to abandon their popular dental software systems (figure 3). Common tasks such as “Chief Complaint,” “Medical,” “Dental History,” and “Treatment Notes” are easy to capture with just touches to an iPad touchscreen interface. Minimal typing and editing are required upon completion of the note. C Notes makes creating and reviewing information quick and easy.

Figure 3: C Notes Interactive Consultation Screen. The doctor conducts a consultation based on the topic selections in the Patient Consultation screen. The Toast (black box) confirms the sentence is written based on the doctor’s selections.

As a member of the team that developed C Notes, the first goal we pursued was to complete the digital BDR. By studying the strengths of current software systems, we were able to identify what was missing. It was an arduous task, but we wanted to generate an incredibly detailed patient-centered note. Software developer Jorge Chao sums it up this way: “In creating C Notes, we soon discovered that C Notes ameliorated the pain of note writing.”

C Notes is capable of capturing 13 of 21 necessary patient-centered items of a BDR that current PM software does not adequately capture. It should be noted that current PM software applications do capture the remaining eight adequately. The trend for PM software is to become more relational with regards to the information it captures and stores, while the development of relation applications through cognitive engineering methods will drive the future of dental software creation.

Figure 4: Generated C Note. The note includes results of the examinations performed and the consultation discussion that followed.

In designing C Notes, we aimed to create a cognitive relational application within the app by creating patient-centered consent forms (figure 5). The consent forms, which are custom written with the press of a button, are based on what was discussed in the consultation appointment. “This is a first of its kind,” says software designer Scott Hedrick. “By keying in what information was covered during the consultation appointment in C Notes, a customized consent form is created for that appointment identifying all of the pertinent information required for a legally binding consent form.”

Figure 5: Consent forms in C Notes are custom generated based on the values selected during the consultation procedure. The form is then read and edited by the patient and doctor. The patient checkmarks each paragraph as being read and then digitally signs the form.

Hedrick adds, “The patient and doctor can review the information in the consent form together while it is fresh in everyone’s minds. The patient then has the opportunity to accept, edit, or reject each paragraph of information. A checkmark by each paragraph indicates that it has been reviewed. Once the consent is agreed upon by the patient and doctor, the patient can digitally sign it.”

Conclusion

Bridging the gap between humans and applications is the ultimate goal of dental software development. Incorporating health information technology to more efficiently provide better patient care requires cognitive thought processes. Efficiently capturing detailed clinical notes in a digital format is a start to effectively creating an environment for the relational use of pertinent clinical information.

References

1. Schleyer T. Electronic Dental Records. 2nd ed. MedLife Quality Resource Guide; 2011 Jul.

2. Schleyer TK, Thyvalikakath TP, Spallek H, Torres-Urquidy MH, Hernandez P, Yuhaniak J. Clinical computing in general dentistry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(3):344–352.

3. Schleyer TK, et al. Electronic dental record use and clinical information management patterns among practitioner-investigators in The Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144(1):49–58.

4. Schleyer T, Spallek H, Hernandez P. A qualitative investigation of the content of dental paper- and computer-based patient record (CPR) formats. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14(4):515–526.

5. Thyvalikakath TP, Schleyer TK, Monaco V. Heuristic evaluation of clinical functions. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138(2):209–218.

6. Himmelstein D, Wright A, Woolhandler S. Hospital computing and the costs and quality of care: A national study.Am J Med. 2010;123(1)40–46.

7. Thyvalikakath TP, Dziabiak MP, Johnson R, Torres-Urquidy MH, Acharya A, Yabes J, Schleyer, TK. Advancing cognitive engineering methods to support user interface design for electronic health records. Int J Med Inform. 2014;83(4):292–302.

8. Emmott, L. Electronic dental records in dentistry. J Am Coll Dent. 2010;77(1):10–12.

9. Tonner J. New charting system seeks to revolutionize malpractice prevention for dentists. DentistryIQ website. http://www.dentistryiq.com/articles/2014/04/new-charting-system-seeks-to-revolutionize-malpractice-prevention-for-dentists.html. Published April 2014. Accessed July 17, 2016.

10. MacKenzie RP. Patient complaints: When the dental board calls. Starnes Davis Florie LLP website. http://www.starneslaw.com/pdf/rpm-when-the-board-calls.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2016.

11. Morse D. Dealing with dental malpractice, part 2: Malpractice prevention. Dentistry Today website. http://www.dentistrytoday.com/practice-management-articles/risk-management/1898-dealing-with-dental-malpractice-part-2-malpractice-prevention. Published March 2004. Accessed July 17, 2016.

12. Schleyer TK. Why integration is key for dental office technology. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;(10)135:4S–9S.

13. Thyvalikakath TP, Monaco V, Thambuganipalle HB, Schleyer TK. A usability evaluation of four commercial dental computer-based patient records.J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(12):1632–1642.

14. DiMatteo A. Welcome to the Age of Digital Dentistry. Inside Dentistry website. https://www.dentalaegis.com/id/2007/08/welcome-to-the-age-of-digital-dentistry. Published July 2007. Accessed July 17, 2016.

15. Carter J. Is it time for a "simple" electronic health record system? EHR Science website. http://ehrscience.com/2015/02/16/is-it-time-for-a-simple-electronic-health-record-system/. Published February 16, 2015. Accessed July 17, 2016.

16. Thyvalikakath TP, Dziabiak MP, Johnson R, Torres-Urquidy MH, Acharya A, Yabes J, Schleyer TK. Advancing cognitive engineering methods to support user interface design for electronic health records. Int J Med Inform. 2014;83(4):292–302.

Author Bio

Dr. Schwartz has authored numerous articles featured in such dental publications as Quintessence of Dental Technology, Inside Dentistry, Dentistry Today, Dental Products Report, and Practical Periodontics and Aesthetic Dentistry. He is featured in National Dental Network’s DVD series, Excellence in Cosmetic Dentistry and has conducted educational videos for Integra Institute and DentalXP. He may be reached at [email protected].