Create a tenfold increase in cosmetic case acceptance.

With the advent of veneers and cosmetic dentistry, the dental profession moved into elective procedures and a more retail-like approach to presenting treatment. Patients became clients and clients wanted to see their choices. At first, the best tools we had were before and after photos, composite mock-ups and diagnostic wax-ups. Then along came the PC revolution and, along with it, computer imaging.

Some of the earliest attempts at computer imaging involved sending 35mm or Polaroid photos of the patient’s smile to a dental laboratory where the imaging would be done and then mailed back to the dental office. It was helpful for presenting cases but there were some drawbacks. It was difficult to see how the teeth were being manipulated. Although it was fairly easy to see if the teeth were significantly longer, it was not as easy to tell if they had been moved laterally to accommodate the desired outcome. In order to predict the true outcome from computer imaging, the dental practitioner was the one who really needed to edit the photos.

Dental office systems for computer imaging started to appear on the market in the 1980s. They have gained moderate acceptance in the dental community. However, many dentists still prefer to work with more familiar materials such as composite mock-ups on the teeth or diagnostic wax-ups on models to forecast possible treatment outcomes.

Recently, in a study published in the Journal of the American Dental Association, computer imaging was demonstrated to be the most successful method for presenting cosmetic dentistry to potential clients. The case acceptance with computer imaging was higher than it was with either composite mock-ups or diagnostic wax-ups.

When compared to mock-ups, wax-ups, or sample before and after pictures, computer imaging has many advantages. It is the most economical way to present potential treatment outcomes. Computer imaging is also the fastest way to prepare a demonstration for the patient. Clients seem to prefer having choices and it is much easier to photo image several versions of the same smile than it is to do several sets of mock-ups. Computer imaging also allows more freedom because, unlike mock-ups, it can demonstrate not only where teeth can be expanded but also where they can be contracted in size for a more esthetically pleasing outcome.

Computer imaging works especially well for tooth contour changes such as gingivectomies, longer incisal edges, and width changes. With the computer, it is easy to present several design options for the patient to compare. This helps the patient get a better sense of what he is trying to accomplish. For example, some alternatives could be flat square teeth verses soft rounded teeth, with or without changes in the tissue contour, four or six teeth as compared to the full mouth.

Computer imaging can expand the patient’s idea for what is possible. Often the cosmetic client will focus on a particular thing he or she does not like. It might be one dark tooth or some crowding and wear.

The conversation will go something like this. “If I could just fix this, my teeth would be fine.”

This is the perfect situation for imaging the teeth on the computer. On a close-up picture of the smile, the particular problem can be edited with the software to show how the desired changes would look in the patient’s smile. Usually this kind of edit is very simple and quick to perform.

null

null

null

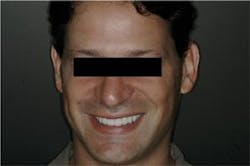

Figure 1: During the above case, the patient stated that the chief concern was worn, dark teeth (top photo). He was presented with three edited images of his smile.

null

Once the primary esthetic concern has been corrected, other esthetic distractions will become more obvious. In a second version of the photograph all of the teeth are edited to simulate a complete smile makeover that corrects all of the esthetic distractions. It is a good idea to present a third option just to give the client one more choice. It could be something as simple as making the complete edit whiter or a little longer or place the new smile in the full face picture. Many people seem to relate even better to a full face picture.

By presenting three different before and after pictures, several things can be accomplished with the patient. The most important is the chance for the patient to relate to the new smile in their face and see what a difference it can make. They can decide for themselves whether resolving the one original concern will be a satisfactory solution. It also shows that other options are possible and opens a new discussion about what they really want to accomplish. By presenting the imaging as a communication tool that can easily be reworked, the patient will feel included in the decision-making process. It helps to present the edited photos as a concept and contrast them with actual photos of other completed cases. The feeling of safety creates an atmosphere of trust and lets the patient know that you can give them exactly what they want without any guesswork.

Because cosmetic dentistry is relatively expensive, the decision to go ahead often requires some gestation time before the client is ready to move forward. It is virtually never an impulse buy. For this reason, it is a good idea to schedule a time to view the imaging after the photos are taken. In addition to allowing some gestation time it also creates another opportunity to build trust and establish yourself as the person to do the work.

Photo editing is potentially very entertaining. For this reason it can be very time consuming to edit the smile in front of the patient. It works better to edit pictures in private and present the changes both on the monitor for more dramatic viewing and in print so the client can take a reminder with them when they leave. If in the course of viewing they want to see another change, then it is a good idea to set the boundaries for minor editing and recommend another appointment for viewing if they start requesting multiple changes.

Once a client has seen what is possible they also see the limitations of their own treatment plan and will often choose to do complete dentistry rather than accept a compromise. In the worst case if the compromise treatment is still what they choose after being fully informed of their choices, the ownership for the final outcome has been transferred to them.

Once the patient agrees to a particular image and decides to move forward with treatment, the image becomes the original blue print for smile design changes. Models of the patient’s teeth along with all the required bite records and the before and after image photos are used as communication tools with the dental laboratory for the diagnostic wax-ups.

Using a matrix formed from the wax-ups the prototype restorations are made directly onto the teeth. At this stage refinements can be made to adapt the new restorations to the patient’s speech and lip support. But because the contours and length were determined beforehand, the shape of the teeth will match the patient’s expectations and minimize changes in the contours when the provisionals are placed.

In the sample case shown here, the patient’s chief concern was the extreme wear and dark colored teeth. He had been referred to have all of his teeth restored. He had already understood his treatment plan and why it required treating at least one entire arch. Although he had accepted the concept of the treatment plan, he was concerned about whether he would be happy with the final outcome. He was not certain how he wanted his teeth to look. The patient had a history of bruxism but no TMJ symptoms. Because of the amount of anterior wear it was clear that the vertical dimension would have to be opened at least a millimeter on the molars.

The patient was presented with three edited images of his smile. In this case the question was how the total smile design would look so every edit included all of the visible teeth (see Figure 1).

The patient chose the look he liked the best and that edited picture was sent to the laboratory for the diagnostic wax-up along with a leveled face bow record, a bite stick, and a written description of the patient’s desires. In this case, the instructions were to wax the models of the teeth to resemble the enclosed photograph and to open the vertical dimension one millimeter (see Figure 2).

null

null

null

From the edited image of the desired outcome the laboratory successfully transferred the smile design to the diagnostic wax-ups, which, in turn, formed the mold for the prototype (provisional) restorations. Once the prototype restorations were refined for occlusion speech and esthetics, records were made and sent to the ceramist with instructions to make the final porcelain look like a refined version of the temporaries with some color characterization and light surface texture. From this information the laboratory was able to make teeth that fulfilled the patient’s expectations at the time of the first try-in without any significant modification (see Figure 3).

null

null

null

Figure 3: The top photo shows the untreated teeth, which is followed by the edited image. The third and fourth photos reveal the prototype restorations and the final restorations, respectively.

null

With careful planning and complete smile design approval at every stage, it is possible to satisfy even the most esthetically sensitive patients. By building trust in the smile design phase of treatment planning and then keeping it by transitioning smoothly from one stage of treatment into the next, the patient and the dentist can have a very rewarding experience (see Figures 4 and 5).

null

null

null

null

null

Not only did the computer imaging help to enroll the patient in his treatment plan, but it served to keep the treatment on track so that the patient had a good experience from beginning to end without any unwanted surprises. Because of the atmosphere of involvement and trust - and because of the predictable outcomes - it becomes easier every day for the dentist to present comprehensive treatment plans with confidence. Using the techniques described in this article, the dentist’s confidence combined with tangible predicted outcomes is a very effective way to increase case acceptance.

The author acknowledges Brad Patrick at Patrick Dental Studios for the porcelain work provided for the case.

Lynn Jones, DDS Dr. Jones is recognized for her excellent cosmetic dentistry and innovative management practices. She is an accreditation examiner for the AACD and lectures extensively on micro-dentistry. Director of “Aesthetics Continuums” for the University of Washington CDE, she maintains a private practice in Bellevue, Wash.