Nonpharmacological management of pediatric anxiety in the dental practice

As dental practitioners, managing patient anxiety is one of the hardest yet most rewarding challenges we face. Countless studies have analyzed the impact of patient anxiety on oral hygiene and attendance history, and it is widely recognized that dental phobia leads to long-term avoidance of regular care.1 This is particularly true for children: their early dental experiences will likely shape their view of the profession for the rest of their lives. With dental treatment often involving injections and high-speed instruments, it is essential that fear and phobias are identified early, to minimize potential long-term repercussions.

This article will summarize the different types and measurement scales of dental anxiety in children, and will suggest nonpharmacological,practical methods to manage it in a general dental practice.

The first challenge in handling an anxious child is identifying the cause of their apprehension. While there are countless classifications for this, the most widely accepted method involves identifying four main diagnostic categories of patient anxiety: type I (simple conditioned phobia), type II (fear of catastrophe), type III (generalized anxiety), and type IV (distrust of dentists).2 It is fundamental for general dental practitioners to correctly identify which category the child falls under, in order to devise the most suitable management strategy. In type I dental phobias, children fear the procedures themselves, as an effect of various conditioning sources (including previous negative experiences), whereas in type II they will often fear potentially life-threatening outcomes of treatment (such as bodily injuries and blood). Type III anxiety tends to present in patients with generalized anxiety disorders, and finally, type IV finds children mistrusting the dental profession as a whole. It is essential we identify the correct origin of the child’s fear in order to maximize the outcome, and overall, the patient’s quality of life.

The second challenge is identifying a way to measure the child’s anxiety levels. While countless anxiety scales are available, the computerized “Smiley Face Program,” suggested by Buchanan in 2005,3 has been proven to be consistent and reliable. This is a four-item scale, where four faces describe possible responses to a variety of dental stimuli. The child is asked to select what face resembles their current feelings toward dental treatment.

Once the child’s anxiety level has been identified, the hard work begins. We must now establish a treatment plan that maximizes the outcome, within the often-strict timeframes of general dental practice. While there are multiple pharmacological methods of managing a child’s anxiety, this paper will lay out three nonpharmacological alternatives.

Strategy 1: Acclimatization

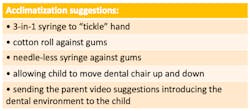

Acclimatization is a technique subconsciously used in countless settings involving children, so why not use it to our advantage in dentistry? Forpractitioners, the overarching principle is that of getting a child used to the dental setting (figure 1). This could involve simply having an informal conversation with the child while they are sitting in the dental chair, allowing them to explore and touch their surroundings. It could also involve parents bringing children along to their own appointments or siblings’ appointments. If this were to happen, however, it is important to avoid situations involving another anxious patient. Once the child is comfortable in the dental chair, one may consider introducing them to dental instruments and materials, such as 3-in-1 syringes or cotton rolls. A popular strategy is that of “tickling” their fingers with the air from the 3-in-1, and then “tickling” their gums with it subsequently. Similarly, allowing them to play with a needleless syringe, prior to pressing it against their gum, allows them to get accustomed to the instruments.4

Strategy 2: Modeling

Modeling is a strategy reliant on the belief that children observe and imitate the behaviors of those around them.5 While this can either be done live or, for example, through a prerecorded video, it is important the model, where possible, is a similar age as the patient. It is also helpful for any model used to be shown entering and exiting the room, to reassure the fearful child that no adverse outcomes are expected.6 Although the use of video recordings can be helpful in this, there may be a stronger argument for the use of siblings in modeling. Watching an older sibling undergo dental treatment calmly and with no adverse effects may encourage a trusting attitude toward the practitioner.

Strategy 3: Distraction

Distraction is a technique that involves diverting the child’s attention away from the clinical setting. Although helpful particularly with younger children, it merely distracts the patient from their fears, rather than directly tackling them. For this reason, it may be wise to pair this technique with other nonpharmacological management strategies to maximize the outcome. Distraction can come in all forms, however in the dental setting, one may find using technology such as tablets or audio devices helpful, playing child-friendly cartoons or audio reels while carrying out treatment.

Key points

The strategies described above are three drops in the ocean of behavior management options for anxious children. The key lies in identifying theIt may be evident to the reader that the options available for the management of an anxious child are endless, and one may find different techniques to be variably suitable in individual cases. It is indisputable, however, that the most important element of method selection is identifying the most sustainable one. By doing so, we can future-proof our care, and promote a fear-free, patient-focused environment.

REFERENCES

- Bowman, L., Gatchel, RJ., Ingersoll, BD., Roberston, MC., Walkcer, C. The prevalence of dental fear and avoidance: a recent survey study. Journal of the American Dental Association. Vol 107, no. 4. Oct 1983, pp. 609-10.

- Liddell, A; Locker, D; and Shapiro, D: Diagnostic categories of dental anxiety: a population-based study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, vol. 37, no.1, Jan. 1999, pp.25-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00105-3

- Buchanan, H. Development of a computerized dental anxiety scale for children: validation and reliability. British Dental Journal, vol. 199, no.6, Sep. 2005, pp. 359-62. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812694

- Hawkins, MWM. Acclimatising child patients. British Dental Journal, 48 (2013).

- Anthonappa, RP., Ashley, PF., Bonetti, DL., Lombardo, G., and Riley, P. Non-pharmacological interventions for managing dental anxiety in children. Cochrane Database Systematic Review. Vol. 6. June 2017. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012676

- Appukuttan, DP. Strategies to manage patients with dental anxiety and dental phobia: a literature review. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dentistry, vol 8, 2016, pp. 35-50. doi: 10.2147/CCIDE.S63626

- Vukovic, N., Fardo, F., and Shtyrov, Y. When words burn – language processing differentially modulates pain perception in typical and chronic pain populations. Language and cognition, vol. 10, no.4, 2018, pp. 626-640. Doi:10.1017/langcog.2018.22

MARTINA OLIVIERI, BDS, BS, is a 27-year-old newly qualified dentist based in Southend, United Kingdom. Having graduated with a degree in biomedical sciences from Kings College London in 2015, she decided to pursue dental school at Barts and the London, graduating in 2020. Olivieri is passionate about all things food, travel, and sports, and enjoys drawing. You can follow her dental journey on Instagram @drmartinaolivieri, or contact her at [email protected].