Treatment considerations for the congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisor

This article first appeared in the newsletter, DE's Breakthrough Clinical with Stacey Simmons, DDS. Subscribe here.

Introduction

In the practice of dentistry, one of the more common dental anomalies we encounter is hypodontia. By definition, hypodontia refers to a condition in which a person is missing one to six teeth. Excluding wisdom teeth, hypodontia reportedly affects between 3% and 8% of the population. (1) The long-term management of hypodontia in the esthetic zone is a particularly challenging situation; therefore, in this article we will limit the scope of discussion to the congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors.

ADDITIONAL READING |Ankylosed primary teeth with no permanent successors: What do you do? -- Part 1

According to epidemiological studies, one or both of the maxillary lateral incisors are congenitally missing in approximately 2% of the population. (1) Maxillary laterals are the third most common missing teeth behind third molars and mandibular second premolars. (1) The patient with congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors will typically present with a complex set of challenges for the clinician to manage. In order to achieve an optimal esthetic and functional result, it is often necessary to establish a coordinated, interdisciplinary approach involving an orthodontist, oral surgeon or periodontist, and a restorative dentist. Careful diagnosis and communication among team members is necessary to formulate a treatment plan that satisfies the patient’s needs and expectations. Some of the many factors that the team must consider in their treatment planning include the patient’s age, facial type and profile, occlusal scheme, spacing, tooth anatomy and condition (shape, color, and size), alveolar bone quality and quantity, gingival display, and biotype. (2-5) In the end, the ideal treatment plan should be predictable, stable, and the least-invasive option available. The scope of this article is not to recommend one specific treatment modality, but rather to identify a few of the clinical considerations that might influence the case management and restorative plan.

Site development

The first step to the successful, long-term management of a congenitally missing lateral incisor case is early detection and referral to the orthodontist. The role of the orthodontist in the early mixed-dentition stage of development is to monitor and guide the eruption of the permanent canine. If the crown of the permanent canine is erupting apical to the primary canine root as it normally does, it may be necessary to selectively extract the primary lateral incisor to encourage the permanent canine to erupt adjacent to the central incisor. The reason for this is twofold. A mesially positioned canine not only provides a natural means for augmenting the supporting tissues, but it also allows for greater flexibility in future treatment planning.

ADDITIONAL READING |Impacted canines and orthodontic treatment

An absence of a permanent lateral incisor will result in restricted growth of the alveolar ridge in the buccolingual dimension, since the only source of development will be from the narrow root of the deciduous lateral incisor. On the other hand, if the orthodontist can manipulate the much larger permanent canine to erupt mesially through the alveolar ridge, its larger root will naturally develop a much thicker buccolingual dimension to the alveolar ridge. Once the canine has erupted, the orthodontist then has the option to distalize the canine into its natural position, leaving behind an augmented ridge. (6,7) Recent studies have shown that space opened orthodontically should remain stable over time (resorption rate of 1% over four years) and may eliminate the need for an additional surgical procedure for alveolar augmentation in the future. (3) This stability is particularly beneficial for implant treatment since fixture placement cannot occur until facial growth is complete. Regardless of whether the definitive restoration is to be an implant or a fixed partial denture or even a removable prosthesis, the esthetics will be vastly improved by this augmentation.

of site development and was later distalized with the aid of orthodontics.

The ridge was significantly augmented but the patient will still likely need

additional grafting at the time of implant placement.

(Photos courtesy of Dr. Kevin Race)

To open or to close

As orthodontists, we are often confronted with the decision to open or close spaces. In the case management of congenitally missing lateral incisors, this becomes particularly complex decision since the result of that decision will ultimately divide our treatment options into one of two categories. One option is to open space for the prosthetic replacement of the missing lateral incisor. The other option is to completely close the space and set up the occlusion for canine substitution. Selecting the appropriate treatment approach is not as simple as it sounds, but rather depends on the patient’s existing malocclusion, growth pattern, profile, smile line, and the size, shape, and color of the canines. Hypodontia is a life-long problem, thus it is important to consider treatment options that are functional, conservative, flexible, and repairable. Opening space allows for multiple prosthetic options to choose from and switch between over the course of one’s life. Closing the space does not offer you quite as much restorative flexibility but it does have numerous other advantages. The substitution of the cuspid for the lateral incisor allows for the early rehabilitation of the patient with conservative reshaping and minimally invasive restorations (e.g., bonding or veneers). This treatment approach eliminates many of the complications that are associated with prosthetic rehabilitation, such as excessive reduction of tooth structure, gingival inflammation, surgical morbidity, incomplete papillary fill, and gingival discoloration. But most importantly, this treatment approach allows the hard and soft tissue architecture to remain in a natural state, making it better suited to respond to the changes over time. (8)

Facial development and continuous tooth eruption

The human dentition and supporting structures must be viewed as dynamic entities, which change in response to age, orthodontic relapse, facial growth, dental eruption, tooth wear, and recession throughout life. Unlike canine substitution, or other tooth-supported prosthetic treatment, implant-supported restorations lack the ability to adapt to the changes. The absence of a periodontal ligament causes the implant to act like an ankylosed tooth, hence requiring that implant placement be delayed until growth cessation has been confirmed by the superimposition of serial cephalometric radiographs taken six months to one year apart. (9,10) Typically male and female patients, with normal growth patterns, are ready for implant placement by the age of 21 and 17, respectively. (11) However, studies have shown that changes in the incisal edge position and facial height are not limited, as often assumed, to just puberty, but can actually continue well after the age of 18 years. Benard et al. followed the vertical changes of maxillary incisors adjacent to implants in adults (40 to 55 years old) for a period of four years and found an infraocclusion ranging from 0.12 mm to 1.65 mm. (12) In a 20-year follow-up study, Forsberg et al. also showed that the anterior facial height increased by 1.6 mm on average with an approximate 1 mm contribution from the eruption of the maxillary incisors. (13)

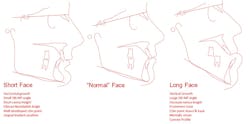

It is important to note that not all faces should be treated the same. Patients with excessively horizontal or vertical growth patterns will show a greater degree of facial change beyond the typical growing years. The short facial type is known as a horizontal grower and has a tendency for a deep bite, while the vertical growing patient has a propensity to develop a skeletal open bite. A cephalometric analysis done by the orthodontist can be used to identify these deviant facial patterns. In a “normal” facial pattern, the relationship between the cranial base and the inferior border of the mandible would create a 32-degreeangle, but in short and vertical facial patterns, the angles would be less than 28 degreesand greater than 38 degrees, respectively. In these types of patients, implant restorations can assume an overly palatal or vertical position, respectively over time; therefore, implant placement might need to be delayed even longer. (14) Ultimately, complications are inevitable with any type of rehabilitation, but those associated with implant restorations in a deviant facial type can be especially difficult. Alternate treatments options that allow the prosthesis to adapt along with the natural dentition (i.e., canine substitution) might be more predictable long term.

reference lines represent the cephalometric measurement of SN-GoGn. The cranial base reference line

runs through the sella tursica (S) and nasion (N), and the mandibular plane (MP) is created by a line

that bisects the angle of the mandible (Gonion) and connects to the point on the chin called gnathion

(Gn). A “normal” SN-GoGn angle is 32 degrees +/- 5 degrees.

Canine substitution

Canine substitution is a conservative, viable treatment approach for the management of missing lateral incisors, but as with any treatment it is up to the clinician to recognize which cases are best suited for a functional and esthetic outcome. According to Kokich and Kinzer, the patient’s facial profile must be straight or slightly convex, and the malocclusion must fall into one of two categories. The first is an Angle Class II malocclusion with minimal crowding in the mandibular arch. This type of malocclusion is essentially a Class II camouflage treatment, which finishes with the molars in Class II and the first premolar functioning as the canine. The second malocclusion suggested by Kokich is an Angle Class II with sufficient crowding in the mandibular arch to justify mandibular premolar extractions and a Class I molar finish. In both scenarios, canine-protected occlusion is not possible, so the final occlusion should finish with an anterior group function in all lateral excursions. (15)

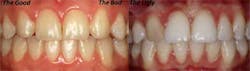

In order to establish anterior group function on substituted teeth, a clinician must critically evaluate the overbite and overjet of each tooth and anticipate any additions or subtractions to the functional surfaces that might be needed. When the orthodontist places the brackets to esthetically align the gingival margins, the substituted cuspid and bicuspid will end up in supra- and infra-occlusion, respectively. Once the ideal position of the gingival framework is properly established, the shapes of the teeth must be adjusted to mimic the replaced tooth. The dimensions of the bicuspid will need to be increased mesio-distally and inciso-gingivally, and the lingual cusp will need to be reduced. The cuspid, on the other hand, will need reduction in the incisal-gingival and mesial-distal dimensions, flattening of the labial surface, and a steepening of the lingual convexity. In order to avoid excessive enamel removal and an increase in color saturation, it is best to perform canine substitution in patients who have teeth of similar overall dimensions to those that they are replacing. Almost all substitution cases will also require additive recontouring of teeth in the form of bonding or veneers with the preferred long-term restoration being the veneer. If an excessive addition or reduction is anticipated, a full-coverage restoration may be necessary and the clinician might want to discuss an alternative treatment approach with the patient, such as opening space and preparing for prosthetic replacement.

contours and positioning were achieved. B: M/D dimensions a bit

excessive and gingival margin positioned to apical. C: Significant

cervical bulge and discoloration evident after recontouring.

Prosthetic treatment

Several restorative options exist for the replacement of the missing lateral incisors. These options include resin-bonded fixed partial denture (Maryland bridge), cantilevered fixed partial denture, conventional fixed partial denture (bridge), and single-tooth implant.

Resin-bonded, fixed partial denture

Of the possibilities for a restorative approach, the resin-bonded FPD is the most conservative option. The resin-bonded FPD requires little to no preparation on the abutment teeth since it relies solely on the bonding adhesive for retention. The downside to this type of prosthesis is that there are very strict clinical criteria that must be met in order to ensure long-term success and predictability. The orthodontist must finish the anterior occlusion with the incisors in an upright position with at least 1 mm of overjet and just enough overbite to disclude the posterior teeth in excursions. (16) Controlling the overbite will decrease the duration and the degree of tipping forces placed on the prosthesis, as well as maximize the surface area available for retainer coverage. Similarly, the proclination of the incisors also plays a vital role in retention of the prosthesis, because as the proclination increases, the functional load changes from a vertical seating load to a tipping tensile load that stresses the adhesive interface. Research has also shown that a more vertically positioned incisor loaded with a shear/compressive force can withstand 40% more load prior to failure than a proclined incisor loaded with a tipping/tensile force. (17) Therefore, the ideal candidate for a resin-bonded FPD is a nonbruxer with short cusps on the posterior dentition and vertically positioned incisors with limited mobility and a shallow overbite.

Dr. Steve Koutnik)

Removable partial denture

Before the days of bonding technology and implants, the options for prosthetic replacement were limited to removable partial dentures and conventional fixed partial dentures. By modern standards of care, neither option is considered the treatment of choice in a typical case. Having said this, it does not mean that there is not a use for them in the management of congenitally missing lateral incisors. In fact, the removable partial denture can serve as a relatively inexpensive, conservative, and reversible means in which to replace the missing teeth and supporting tissues. Some of the disadvantages to the removable partial denture are their fragility, bulky design, lack of retention, interference with speech and taste, and compromised esthetics. The biggest downside to a removable partial denture is the potential for the breakdown of a potential future implant site. With a removable partial denture, the orthodontically created interradicular space is prone to relapse, and the hard and soft supporting tissues are susceptible to breakdown as a result of long-term, functional loading. For many clinicians, the ideal interim restoration to manage the case between the completions of orthodontic care and implant placement is still the resin-bonded, fixed partial denture.

Conventional, fixed partial denture

The least conservative of all tooth-supported restorations is a conventional, full-coverage, fixed partial denture. Although conventional, fixed bridges are more comfortable and esthetic than removable partial dentures, they require gross reduction of healthy tooth structure, which is generally contraindicated in young patients. With today’s materials, fixed bridges offer excellent results from an esthetic and functional perspective, but because they still require a significant amount of tooth reduction, their use should be limited to situations where a conventional bridge already exists or the condition of the abutment teeth (i.e., wear, caries, fracture, etc.) would dictate a more aggressive preparation.

Endosseous implant

As we have seen thus far, there are multiple restorative options that exist for the replacement of the congenitally missing lateral incisor. In recent years, the most common treatment alternative has undoubtedly been the single-tooth, endosseous implant. The predictability, conservative nature, and long-term success rates of implants have made them an obvious restorative choice, especially in cases where the adjacent teeth are healthy, unrestored, and of normal size and shape. (18,19,20) In modern dentistry, osseointegration is no longer the benchmark for success. Success is measured by the esthetics and the clinician’s ability to replicate a natural-looking crown while maintaining a hard- and soft-tissue framework that blends in seamlessly with the surrounding tissues. This is no easy task. In order to achieve success, several factors must be evaluated and accounted for in the early stages. The first and foremost is space appropriation.

site development. B. Final restorations: No. 7 implant crown and No. 10

veneer. (Photos courtesy of Dr. Steve Koutnik)

In restorative dentistry we have multiple ways to determine the appropriate space for a missing tooth. The simplest way is to assess the contralateral side. Unfortunately, this method is not adequate if there is a missing or peg-shaped contralateral tooth.

The second is the golden proportion, which states that each tooth in the smile should be visually 61.8% bigger than the tooth distal to it. (3)The golden proportion is good in assessing the visual harmony of a restoration, but it is not as useful in determining the exact mesial/distal dimension that is required for the implant restoration.

The third method is the Bolton analysis. This method allows the clinician to mathematically determine the amount of mesial/distal tooth dimension that is needed in the maxillary anterior to establish an ideal overbite and overjet while placing the canines in a Class I relationship with the mandibular teeth. Bolton’s measurement involves dividing the sum of the mesiodistal width of the mandibular six anterior teeth by the sum or the mesiodistal width of the maxillary six anterior teeth. The ideal ratio comes out to be 0.78 and can be used to back-calculate the ideal missing tooth dimension.

The fourth and final method simply allows the occlusion to dictate spacing. The orthodontist will set up an occlusal scheme that allows for canine disclusion and ideal esthetic positioning of the existing anterior teeth; then the restorative dentist can follow up with a diagnostic wax-up. In many cases the remaining space will be in the range of 5 mm to 7 mm. (21)

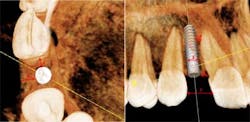

Now that we have we have determined how to establish the space required for a proportional restoration, we must determine if the space requirements will allow for the placement of the implant fixture. As a general rule, it is recommended to allow between 1.5 mm and 2.0 mm of space between the implant platform and the adjacent teeth for the development of the papilla. If the edentulous space measures 7 mm and we need a minimum of 3 mm for papilla formation, then that leaves the surgeon an adequate amount of space (4 mm) for the implant fixture. But if the edentulous space only measures 5 mm, then there would be insufficient space for both a traditional narrow platform implant and papilla formation. (22) In the later situation, a compromise has to be made and the patient should be properly informed.

represent the recommended spacing parameter to establish a stable

and esthetic replacement of the maxillary lateral incisor.

The orthodontist and the surgeon must also take into account the space appropriation in the interradicular area as well. The minimum spacing between the roots is generally 5 mm. This amount of space will allow the implant to be surrounded by 0.75 mm and 1.0 mm of bone, which is sufficient to support normal functional loading and ensure good long-term osseointegration. (22) During the space opening aspect of orthodontic care, the orthodontist must make a compensating bend to diverge the roots, especially when canines are initially distal angulated, since the canine root apex inevitably lags behind the crown when distalized. The orthodontist also has to pay particular attention to the skeletal relationship of the patient in these cases because in an Angle Class III tendency type case, the maxilla is narrow and the crowns tend to be tipped labially, which in turn results in adequate space for the restoration but insufficient space at the apex for fixture placement and may necessitate an alternative type of restoration or a shorter implant fixture. (3,6)

In any case, but especially Angle Class III cases, it is good practice for the restorative dentist or surgeon to take a periapical radiograph prior to the removal of the orthodontic appliances to ensure that adequate interradicular space has been established. Once the root position has been confirmed and appliances are removed, it becomes especially important to establish a retention protocol that will prevent relapse of the root position. Removable appliances are adequate to maintain the interradicular spacing in the short-term, but many times these cases need to be retained for a number of years until growth is complete and a more long-term provisional is recommended. In cases with a high relapse potential, a resin-bonded fixed partial denture should be considered. This type of restoration has the advantage of being esthetic, conservative, and eliminates compliance issues, all while maintaining the established tooth positions and site development.

and a narrow maxilla limits the orthodontist’s ability to torque the

roots and creates a convergence of the roots, which limits the

apical interradicular space for implant placement.

Summary

The treatment of congenitally missing, maxillary lateral incisors is very challenging and complex, requiring very careful case selection, treatment planning, and often the coordinated interdisciplinary efforts of the orthodontist, periodontist or oral surgeon, and restorative dentist. The orthodontist plays a very vital role in the early management of these types of cases and ultimately requires that the orthodontist think like a restorative dentist and a surgeon, for he or she must understand where the teeth are best positioned for each different type of restorative situation. It is imperative that there is continuous communication among team members. The two categories of treatment options, which include space closure with canine substitution and space opening with prosthetic replacement, each have their own separate criteria for tooth placement, and many times the final esthetics are determined by the initial evaluations and recommendations made by the orthodontist. The orthodontist is responsible for assessing facial types, growth patterns, tooth positions, occlusal schemes, but more importantly the orthodontist is responsible for putting the teeth in a position where the surgeon and the restorative dentist can execute a conservative and esthetic restoration.

At the current time, the two most commonly recommended ways to manage congenitally missing laterals are canine substitution and a single-tooth implant. The other prosthetic alternatives that include the resin-bonded, fixed partial denture, the conventional fixed partial denture, and removable partial denture can also be used with a high degree of success if used in the correct situation. In the realm of contemporary dentistry, implants are probably the most favored treatment modality for replacing missing anterior teeth. The implant approach in the anterior region, however, is a delicate situation, which can be challenging esthetically, especially in the long term. In this scenario, it is necessary to work as a team in order to develop the ideal conditions before and after implant placement. In today’s dentistry, where there is such a high degree of emphasis placed on esthetics, it is not possible for a dentist to work alone, especially when dealing with challenging situations like the congenitally missing lateral incisor.

Although this article did not specifically attempt to recommend a particular treatment modality, it did identify the available options and discussed some of the advantages and disadvantages of each one. In this particular clinical situation, there is no treatment that is clearly the best for every case. Therefore, it is imperative to manage these patients from an interdisciplinary diagnostic and treatment perspective. Together with teamwork and open communication we can produce predictable and esthetic treatment results.This article first appeared in the newsletter, DE's Breakthrough Clinical with Stacey Simmons, DDS. Subscribe here.ADDITIONAL READING ...

Why implementing a system of checks and balances in orthodontics is important

Orthodontics case study: treat 'the face' not 'the teeth'

References

1. Polder BJ. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of dental agenesis of permanent teeth. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:217-226.

2. Sabri R. Management of missing maxillary lateral incisors. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130(1):80-84.

3. Spear FM, Mathews DM, Kokich VG. Interdisciplinary management of single tooth implants. Semin Orthod. 1997;3(1):45-72.

4. Kokich VO Jr. Early management of congenitally missing teeth. Semin Orthod. 2005;11(3):146-151.

5. Kinzer GA, Kokich VO Jr. Managing congenitally missing lateral incisors. Part II: tooth-supported restorations. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2005;17(2):76-84.

6. Kokich VG. Maxillary lateral incisor implants: planning with the aid of orthodontics. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:48-56.

7. Ostler MS, Kokich VG. Alveolar ridge changes in patients congenitally missing mandibular second premolars. J Prosthet Dent. 1994;71:144-149.

8. Zachrisson B, Rosa M, Toreskog S. Congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors: Canine substitution. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139:434-445.

9. Fudalej P, Kokich VG, Leroux B. Determining the cessation of vertical growth of the craniofacial structures to facilitate placement of single-tooth implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131(Suppl):559-567.

10. Kokich VG. Managing orthodonti-restorative treatment for the adolescent patient. In: MxNamara JA, Brudon WI, ed. Orthodotics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. Ann Arbor, MI: Needham Press; 2001:423-452.

11. Jemt T, Ahlberg G, Henriksson K, Bondevik O. Changes of anterior clinical crown height in patients provided with single-implant restorations after more than 15 years of follow-up. Int J Prosthodont. 2006;19:455-461.

12. Bernard JP, Schatz JP, Christou P. Long-term vertical changes of the anterior maxillary teeth adjacent to single implants in young and mature adults: A retrospective study. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:1024-1028.

13. Forsberg CM, Eliasson S, Westergren H. Face height and tooth eruption in adults: a 20-year follow-up investigation. Eur J Orthod. 1991;13(4):249-254.

14. Heij DG, Opdebeeck H, Kokich VG. Facial development, continuous tooth eruption, and mesial drift as compromising factors for implant placement. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2006;21(6):867-878.

15. Kokich VG, Kinzer GA. Managing congenitally missing lateral incisors, part 1: Canine substitution. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2005;17:1-6.

16. Creugers NH, Kayser AF, Van’t Hof MA. A seven-and-a-half-year survival study of resin-bonded bridges. J Dent Res. 1992;71:1822-1825.

17. Spear F, Matews D, Kokich VG. Interdisciplinary management of single tooth implants. Semin Orthod. 1997;3:45-72.

18. Henry PH, Laney WR, Jemt T, et al. Osseointegrated implants for single tooth replacement: a prospective 5-year multicenter study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1996;11:450-455.

19. Garber DA, Salama MA, Salama H. Immediate total tooth replacement. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2001;22:210-218.

20. Mayer TM, Hawley CE, Gunsolley JC, Feldman S. The single-tooth implant: a viable alternative for singe-tooth replacement. J Periodontol. 2002;73:687-693.

21. Bolton WA. Disharmony in tooth size and its relation to the analysis and treatment of malocclusion. Am J Orthod. 1958;28:113-130.

22. Saadun AP, LeGall M, Touati B. Current trends in implantology: part II—treatment planning and tissue regeneration. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 2004;16:707-714.

23. Gottlieb B, Orban B. Active and passive eruption of the teeth. J Dent Res. 1933;13:214-224.

24. Garguilo AW, Wentz FM, Orban B. Dimensions and relations of the dento-gingival junction in humans. J Periodont. 1961;32:261-273.