Clinical considerations in retreatment of a failed endodontic procedure

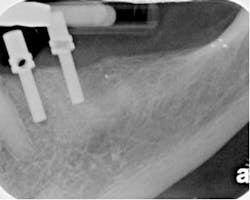

By Richard E. Mounce, DDSThe patient pictured in Fig. 1A-B was referred for retreatment of No. 18. The subjective and objective findings, treatment options, and the clinical strategies employed for management of this clinical case are discussed.

Figs. 1A-B: The clinical retreatment described.The patient’s chief complaint was a mild buccal swelling beside No. 18 that had come and gone several times over the past few years. While fluctuant, the swelling was minor. The tooth was sensitive to percussion and palpation, without mobility, and probings were within normal limits. The root canal was treated many years before. At the time of treatment, the patient was not informed of anything unusual or that any further treatment needed to be completed in the future. Mild symptoms begin to arise approximately five years ago, with the patient experiencing a dull ache in the area. The patient’s general dentist told him to get the tooth retreated. He did not. Upon the reappearance of symptoms, the patient sought definitive treatment and was referred to me. The patient’s pain was mild to moderate. There was discomfort in chewing as well as spontaneous and nocturnal discomfort. There was no evidence, as expected, of sensitivity to hot or cold liquids. The patient was not taking any medications for pain at the time of the examination. The patient’s medical history was noncontributory. Radiographically, furcal and apical pathology was evident. The distal canal appeared to have a single cone of gutta percha in place, and while there was opaque filler near the orifice, there was no apparent instrumentation of the mesial root below the coronal third. Radiographically, some type of instrumentation into the coronal third of the mesial root had been attempted without apparent success to locate the canals of the apical half of the root. It was unknown if there was a perforation at the cervical level of mesial root of No. 18. The mesial aspect of the crown margin appeared open. Radiographically, a lack of coronal seal was evident. The apex of the distal root had external resorption and its management was expected to be slightly more complicated than that of the mesial root, assuming patency of the mesial root could be achieved. Clinically, the patient was given the option of extraction or retreatment. The patient chose retreatment. The procedure, alternatives, and risks were explained and the patient’s questions answered. Clinical considerations in retreatment 1) If the mesial root was found to be perforated at the cervical region upon access, the prognosis for this tooth would drop given the long-term microbial assault that this tooth would have undergone from the lack of coronal seal. Even if the mesial root were not perforated, attempting to find the canals would risk perforation in removal of dentin given the position of the tooth, the lack of root width, and reduced margin of error for canal location. 2) Patency in the mesial root could not be assured. Even if the canals were located as obviously they were, preoperatively, it would not be possible to know in advance that if these canals were negotiable. Locating the canals and negotiating them to the apex required at a minimum the use of a surgical operating microscope (Global Surgical, St. Louis, Mo.) or the use of loupes such as the 4.8x HiRes Class IV loupes (Orascoptic, Middleton, Wisc.). The techniques used for location of the canals in the mesial root of the lower molar are discussed below. 3) Given the appearance of the mesial root orifice, it cannot be ruled out that the material present is not a paste of some kind that possibly had dissolved. In any event, what was absolutely clear was that saliva and bacteria had contaminated the obturation due to coronal leakage and as a result, endodontic surgery was contraindicated and retreatment the favored means of resolution for the clinical symptoms. 4) Given the resorption of the distal root, the indication for MTA (Dentsply Tulsa Dental Specialties, Tulsa, Okla.) as an obturation material could not be ruled out. 5) It was unknown at the time of the examination whether it would be mandatory for the treatment to be carried out in one visit or two. If the apex of the tooth could not be cleaned and dried and or purulent drainage were present upon access, it is entirely possible that an interappointment dressing of calcium hydroxide would be needed. Because there was no facial swelling or severe sensitivity, there no indication for incision and drainage nor for leaving this tooth open. If the tooth could be cleaned and dried at the apex and cleansing, shaping, and obturation was ideal, treatment of this tooth could be planned for one visit. 6) It is essential that the irrigation of this tooth be optimized through activation. Common means to activation include ultrasonic, sonic, negative pressure, rotational means, among others). It is clear from the endodontic literature that the microbial biofilm is present in this tooth and all means necessary and at the disposal of the clinician should be used to eliminate the biofilm. In this clinical case, the irrigant was heated and ultrasonically activated. The primary irrigant used was 2.0% chlorhexidine (CHX), and this irrigation was alternated frequently with a liquid EDTA solution (SmearClear, SybronEndo, Orange, Calif.). At the end of the instrumentation, both of these irrigants were ultrasonically activated using a file adapter and ultrasonic file blanks. The Ultrasonic File Adapter and MiniEndo (SybronEndo, Orange, Calif.) were used in combination with ISO size #20 ultrasonic file blanks (EMS, Dallas, Texas). 7) Placing a postendodontic coronal seal is essential. In addition to the treatment being carried out under the rubber dam, the placement of a coronal seal was planned. The worse outcome possible would be to complete the treatment, place a temporary filling, and have the patient forget or neglect to get the needed coronal seal and repeat the sequence of events that contributed to the failure in the first place. Clinical retreatment Access of this tooth resulted in the porcelain fracturing off the occlusal. While this had no effect on the treatment, after the access was optimized and all of the canal orifices exposed, the gutta percha was easily removed from the distal root. It was found that the material above the mesial root orifices was not gutta percha. There was no restoration in the pulp chamber. The chamber floor was discolored and had been subjected to leakage. Ultrasonic tips were used two-thirds down the mesial buccal and mesial lingual canals in order to locate the canals. Such an action is highly at risk of perforation. It should not be attempted without significant training and enhanced visualization and magnification in order to minimize the risk of perforation and removal of unnecessary removal of tooth structure that could later put the tooth at risk of vertical fracture.Once the mesial buccal and mesial lingual canal were located in the mesial root, a #6 hand K file was used to negotiate these canals. After the #6 hand K file was able to spin freely in the mesial canals, a glide path was prepared up to the size of a #15 hand K file. After the glide path was prepared, rotary nickel titanium files were inserted into the mesial root. The Twisted File (TF) (SybronEndo, Orange, Calif.) was used to shape the mesial canals to a maximum taper of .08 and a master apical diameter of an ISO tip size #40. The sequence of instrumentation was the .08/25, followed by the .06/30, .06/35, and .04/40. Obturation was performed with RealSeal bonded obturation. This obturation was carried out with the SystemB technique delivered via the Elements Obturation Unit (SybronEndo, Orange, Calif.) and the use of RealSeal master cones. Upon shaping of the distal canal, it was determined that the apex, while resorbed, did not need to be sealed with MTA (Dentsply Tulsa Dental Specialties, Tulsa, Okla.), as a fit of a master cone with tugback was possible and predictable. This retreatment could just have easily been performed with RealSeal One Bonded Obturators (SybronEndo, Orange, Calif.). In any event, whether in the master cone or obturator form, bonded obturation has been shown in vitro and in vivo to reduce the migration of bacteria in a coronal to apical direction in a statistically relevant fashion relative to gutta percha. As an aside, the distal root has a wide ribbon-shape canal from buccal to lingual and its obturation was carried out in the same manner as the mesial with the exception that the canal was laterally condensed first after placement of the master cone with tugback. After lateral condensation, the canal was downpacked with the traditional SystemB technique, again using the Elements Obturation Unit as above. A flowable composite was bonded into the crown to reestablish coronal seal. The patient was instructed to get a new crown. The management of a failed root canal has been described. Emphasis has been placed on diagnosis, restorability, determining existing iatrogenic events, and preventing future ones. Preparing the optimal taper, master apical diameter, and bonding the obturation has been addressed as well.I welcome your feedback.

Richard E. Mounce, DDS, is the author of the nonfiction book “Dead Stuck” — “one man's stories of adventure, parenting, and marriage told without heaping platitudes of political correctness.” Pacific Sky Publishing. DeadStuck.com. Dr. Mounce lectures globally and is widely published. He is in private practice in endodontics in Vancouver, Wash. Contact him at [email protected].