By Anthony T. Borgia, DDS, MHA

May 20, 2013

One area in dentistry that is frequently challenging to correctly diagnose occurs when patients present with teeth that are both endodontically and periodontally involved. The two conditions are often seen together, but occasionally the clinician may confuse one for the other, resulting in treatment plans that may be based on incorrect information. Unwarranted root canal therapy or needless tooth extraction can result if an abnormal periodontal probing or patient discomfort is misinterpreted. This article will explore and define the three possible presentations of endodontic-periodontal relationships that all clinicians face on a daily basis, and hopefully provide clarity to make accurate diagnosis simple and routine.

Be in the know on endo

10 steps to efficient endo in the general practice

For differential diagnosis and treatment purposes, “endo-perio” lesions are classified as either:

- Primary endodontic disease

- Primary periodontal disease

- Combined diseases. Combined diseases are further subdivided into:

- Primary endodontic disease with secondary periodontal involvement

- Primary periodontal disease with secondary endodontic involvement

- True combined lesions

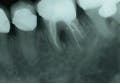

In primary endodontic disease, an acute exacerbation of a chronic apical lesion that has been caused by a necrotic pulp may result in temporary loss of alveolar bone, which can provide an avenue of drainage through the PDL into the gingival sulcus. Normally, this drainage is either not present or is seen as a sinus tract appearing in the attached gingiva. Radiographically, this condition may present as a periodontal problem, demonstrating severe bone loss. A so-called “pseudopocket” may form, with probing depths to or even past the apex of a root. The furcation of a multi-rooted tooth may also be seen to be involved (Figure 1). Diagnostically, pulp testing must be performed, specifically with thermal stimulation. A “no response” is indicative of a non-vital pulp and is diagnostic for endodontic involvement. After establishing the reason the pulp became non-vital and ruling out vertical crown and/or root fracture, conventional root canal therapy is performed (Figure 2). Removal of bacteria, bacterial by-products, and other immunogenic materials from the root canal system, followed by proper obturation, allows surrounding bone to recover and heal normally, with resolution of all periodontal pockets (Figure 3). Endodontic disease may be thought of as an “acute” process as opposed to a “chronic” process, and once the primary cause of the infection (the non-vital pulp) has been addressed and resolved, normal healing ensues.

Periodontal maintenance: kicking it up a notch!

As opposed to endodontic disease, periodontitis is normally considered to be a chronic process. (The exeption, of course, is an acute periodontal abscess caused by the introduction of a foreign body. In that case alone, once the offending material is removed, the periodontium recovers.) Clinical examination usually reveals multiple areas of bone loss, which can be mild, moderate, or severe, and either generalized or localized. Pocket depths can vary widely and are not localized to one specific area of any given tooth or teeth. True lesions of periodontal origindo not involve the apex of the roots, as may be found in lesions of endodontic origin. While endodontic problems are immediately resolved with successful root canal treatment, successful periodontal therapy is ongoing for the life of the patient and involves care from both patient and provider. Pulp testing a periodontally-compromised tooth suspected of endodontic involvement that returns a positive response immediately rules out a lesion of endodontic origin. Since lesions of endodontic orign only develop when a non-vital pulp is present, any vitality demonstrated from an involved tooth indicates that root canal therapy would not change the prognosis of the periodontal situation. However, surgical intervention and bone grafting can result in satisfactory healing of the periodontium.

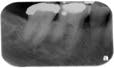

Most difficult of the endodontic-periodontal relationships to understand are the combined lesions. First, an untreated, long standing endodontic lesion may result in chronic, marginal periodontal breakdown. This is characterized by a non-vital pulp response, a deeply probing pocket, and the usual signs of periodontal disease such as plaque, calculus, and other indications of poor oral hygiene. In this case, the affected tooth requires both root canal threapy and localized periodontal treatment, such as scaling and root planing. Endodontic therapy alone may not resolve the existing pocket until the prognosis of periodontal resolution can be determined. Second, a periodontal pocket that has been left untreated, causing the resulting bone loss to expose the apical foramen to the oral environment, can lead to a “retrograde pulpitis” and subsequent necrosis of the pulp (Figures 4, 5, and 6).

Bacteria enter the root canal system through the apical foramen or lateral canals, requiring root canal therapy to remove the dead or dying pulp. Diagnostically, there may be a response to thermal stimulation, depending upon the extent of the pulpal breakdown, but root canal therapy is required nonetheless. The prognosis in this situation is strictly dependent upon the condition of the periodontium and the extent to which it responds to periodontal treatment (Figures 7, 8).

Finally, while true combined endo-perio lesions are much less frequently encountered, they are found when periapical endodontic lesions increase in size and enlarge in a coronal direction, while at the same time a periodontal pocket progresses apically and the two lesions subsequently join. These teeth require both root canal therapy and aggressive periodontal treatment if they are to survive in the dental arch.

Recognizing the significance of endodontic-periodontal relationships and how the two conditions interact with each other is an essential part of everyday dental diagnosis. A clear understanding of these frequently confused pathological conditions provides the clinician with the correct skills to properly assess a patient’s problem, develop an effective treatment regimen, better establish a long-term prognosis, and ultimately deliver the best possible care that benefits all patients to the highest possible level.