Assessing case difficulty and managing risk factors: discussion of a challenging tooth

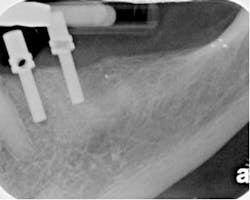

By Richard E. Mounce, DDSThe tooth pictured in Fig. 1 (No. 15) was referred to me for completion by a general practitioner. The final result of treatment is pictured in Fig. 2. The preoperative treatment planning and clinical management of this tooth is detailed below. The strategies employed in this case have clinical utility across a wide variety of anatomies and are discussed for their application in these anatomies.

Fig. 1: The clinical case after referral as described in the article.

Fig. 2: The clinical case after completion with the Twisted File and RealSeal bonded obturation (both SybronEndo, Orange, Calif.). The patient was asymptomatic upon examination in my office. The referring doctor accessed the tooth the previous day. The general practitioner provided no information as to why the case was referred. The tooth was within normal limits as to percussion, palpation, mobility, and probings. There was a temporary filling in the access. Four walls of coronal tooth structure remained. There was no evidence of apical radiographic pathology. The clinical diagnosis was a moot point because the tooth had already been accessed. The initial access of the coronal third of the various roots was minimal. It was expected upon access to have some remaining vitality of the pulp tissue below the coronal third.Radiographically, there were three fused roots and a moderate to severe curvature to both the mesial buccal and the distal buccal roots. There was no obvious perforation of the pulpal floor. The procedure was explained to the patient, as well as the need for a buildup and crown after the root canal. The alternatives and risks to the treatment as well as all the patient’s questions were discussed in detail before commencing.Anticipated risk factors1) Whenever one individual has started a root canal, the second clinician into the tooth should consider the possibility that the canals may be blocked with debris and/or that apical patency may be difficult to obtain. It could not be assumed that after access the canals would be negotiable and/or that some other iatrogenic event may not be found. Such blockage is a frequent finding in canals that have been started and then referred for completion. Especially if diligent care is not taken in early enlargement, inadvertently debris can be picked up on files, be they rotary nickel titanium (RNT) or hand K files, and propelled apically. Canal blockage as a result of this debris propulsion is predictable if: a) the canal is small, curved, and/or calcified; b) files too large for the indication were inserted with undue force; c) an incorrect sequence was used; d) a glide path was not present when the RNT was inserted; e) irrigation is inadequate; f) patency files are not copiously used. A glide path is a canal that is open to the initial diameter of a #15 hand K file. Some canals will have this initial diameter present naturally and in other canals, this initial diameter will have to be prepared manually. Blockage is entirely preventable if the clinician will focus during early negotiation of canals on the use of pre-curved #6 and #8 hand K files and glide path creation. In essence, before RNT files are used (other than to enlarge the orifice slightly for access), these small hand K files should be used to assure that the canal is open, patent, and negotiable to the minor constriction (MC) of the apical foramen. 2) In this clinical case, RNT were at risk for breakage due to the calcification, curvature, and minimal initial diameter of the canal anatomy present. While many cases are amenable to a crown down approach to instrumentation for the preparation of the master apical taper (i.e., the basic preparation of the canal before apical enlargement), this tooth was not one of those cases. In essence, to move from larger tapers and tip sizes to the apex in this clinical case after a glide was created would predispose the RNT to fracture, to excessive torsion, and/or cyclic fatigue. A far more predictable strategy in such complex anatomy would be to assure oneself that he/she has a glide path to the MC and then to use RNT files of smaller tapers to larger tapers (in essence to utilize a step-back technique). Clinically, this means that after the glide path was created, the canal would be prepared to a .04 taper first, then a .06 and larger as indicated. Such a step-back approach for this root complexity is predictable and diminishes the probabilities of RNT file fracture.3) An MB2 canal is highly likely to be located in this tooth. The needed lighting and magnification to make this evident should be on hand from the initial access. The surgical operating microscope (SOM) (Global Surgical, St. Louis, Mo.) is ideal for this purpose.4) Length control might be problematic if the canals cannot be opened and apical patency achieved. A lack of apical patency would mean that instrumentation would be taking place in a canal that cannot be irrigated ideally. Because the canal cannot be cleared of debris completely, such a canal is highly at risk of RNT fracture if the RNT is forced apically after it reaches the level of the blockage. As a result, extreme caution is advised using RNT files at the apical extent of blocked canals. Clinical strategies to manage the clinical challenges above: discussing the steps taken1) After profound anesthesia, the access was refined so as to allow unobstructed straight-line access to each of the orifices. An MB2 canal was immediately observable after pulling back the mesial wall of the existing access preparation.2) The orifices of the MB, DB, and palatal canal had all previously been enlarged with a RNT orifice opener. Rather than further enlarge the orifices, an attempt was first made to achieve apical patency. To place RNT files into the orifices first without assuring patency at all levels of the canal would be to invite fracture of the RNT as well as to push debris apically. In this case, in the presence of 5.25% sodium hypochlorite, a #6 hand K file was placed into each of the canals in order to achieve apical patency as described below. All of the canals in the mid root and apical regions of the canal were calcified, curved, and required numerous insertions of a pre-curved #6 hand K file to achieve apical patency. In each of the canals, the #6 hand K file was “danced” in the canal and inserted in various orientations in order to find the true canal path. Once the MC was felt, the true working length (the position of the MC) was confirmed with an apex locator. It is noteworthy that the achievement and maintenance of apical patency has one other significant advantage (in distinction to its loss and resultant blockage) in addition to that above. From the February 2009 (Volume 35, Issue 2, Pages 189-192) issue of the Journal of Endodontics, it was found that achievement of patency reduces the postoperative pain. To quote the article: “This study compares the incidence, degree, and length of postoperative pain in 300 endodontically treated teeth, with and without apical patency ... There was significantly less post-endodontic pain when apical patency was maintained in nonvital teeth ....” In essence, it has value from a pain management and reduction of postop inflammation perspective to achieve and maintain patency because the incidence of iatrogenic outcomes is reduced as well as provide improved possibilities for cleaning and shaping the canal to the MC. After apical patency was achieved with the #6 hand K file, the file was left in the canal at the MC and the M4 Safety Handpiece was attached. The M4 reciprocates a hand K file 30 degrees clockwise and 30 degrees counterclockwise. In essence, it replicates the motion of hand K file watch winding used to negotiate and enlarge canals. The M4 is used with a 1 mm to 3 mm vertical amplitude of motion at 900 rpm. The M4 is attached via an E-type coupling to an electric endodontic motor. The M4, used in this manner, enlarges the canal from the diameter of a #6 hand K file to that of a #8 hand K file. Reciprocating the #6 hand K file to this diameter takes approximately 15 to 30 seconds. The clinician should feel the hand K file reciprocate more easily and give less tactile resistance to the vertical movement of the file as reciprocation progresses. After the #6 hand K file is reciprocated, the #8 hand K file follows. Specifically, after the canal is irrigated and a #6 hand K file is placed to make sure that the canal is open, patent, and negotiable, the #8 is reciprocated in the same manner as the file that preceded it. Using the M4 sequentially in this manner, after reciprocating a #10 hand K file, the canal will be enlarged to the diameter of a #15 hand K file and ready for RNT enlargement. As an aside, the hand K file is never placed into the M4 and driven to length. In other words, the hand K file is placed to the true working length (i.e., the MC) manually, and then the M4 is placed over the head of the hand K file. Driving a hand file in the M4 and attempting to get to length is the harbinger of a ledge, blockage, or other iatrogenic event. 3) In this clinical case, after M4 reciprocation, the Twisted File* (TF) was used to prepare the canals. TF is available in .04/25/40/50, .06/25/30/35, .08/25, .10/25, and .12/25. After the preparation of the glide path, the .04/25 TF was taken to the TWL of each canal followed by the .06/25 TF and .08/25 TF. This sequence of files created the “basic preparation.” In other words, the canals had the final taper prepared to the MC, in this case of .08 taper in all canals. The term “basic preparation” in this context refers to the master apical taper created (final prepared taper) prior to the enlargement of the master apical diameter; i.e., the largest size taken to the apex (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: The Twisted File (SybronEndo, Orange, Calif.)TF was chosen for its flexibility, cutting ability, and fracture resistance. The file is twisted to create its cutting flutes; it is not manufactured by grinding, as are virtually all the other systems available on the market at this time. Grinding imparts surface imperfections onto the metal of the file, a limitation that the TF does not possess. These surface scratches and micro-cracks are the likely propagation points of torsional and cyclic fatigue failure of RNT files. TF, because its cutting flutes are not manufactured by grinding (they are twisted while the nickel titanium is in an intermediate crystalline phase configuration between austenite and martensite, known as the rhombohedral phase), possesses improved fracture resistance, flexibility, and cutting ability relative to ground files.As an added benefit, TF can often, in 90% of the clinical cases encountered, create the basic preparation in no more than two files. This clinical case was exceptional in its difficulty, as it required three files to make the basic preparation to a final .08 taper before production of the enhanced master apical diameter.4) After the basic preparation was made in all canals to a .08/25 TF, the master apical diameter was shaped. To accomplish this goal, the .06/30 TF was inserted once followed by the .06/35 TF and .04/40 TF. After each insertion and prior to the next insertion of varying sizes, the canal was irrigated and recapitulated.5) The MB2 canal was not negotiable at any time. Despite adequate dentin removal over the orifice, the canal was not negotiable, even a #6 hand K file. Rather than create a perforation, the canal was left untreated. The wiser alternative to risking perforation in an attempt to negotiate the MB2 was to leave it as it was.6) After canal preparation, the canal was irrigated with SmearClear.* SmearClear is a liquid EDTA solution used to remove the smear layer and open the tubules to make possible bonded obturation with RealSeal* bonded obturation. After the rinse with SmearClear, the canals were flushed with distilled water and dried.7) .06/20 RealSeal Master cones were trimmed and tugback achieved. The roots were filled with the SystemB technique delivered via the Elements Obturation unit.* Alternatively, this tooth could have been obturated with RealSeal One Bonded Obturators.* It is a matter of personal preference whether a bonded obturator or master cone technique would be more appropriate. Bonded obturation was chosen for its improved resistance to coronal microleakage relative to gutta percha as demonstrated by in vitro and in vivo studies (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: The RealSeal bonded obturation kit. (SybronEndo, Orange, Calif.)8) The referring doctor had requested that they do the crown buildup. As a result, a layer of flowable composite in the form of PermaFlo (Ultradent, South Jordan, Utah) was placed over the obturation to protect it from coronal microleakage until such time as the crown buildup was placed. The clinical management of a challenging upper molar has been described. Emphasis has been placed on avoiding iatrogenic issues such as canal blockage and perforation as well as providing an excellent glide path prior to the use of RNT files such as the Twisted File. I welcome your feedback. *SybronEndo, Orange, Calif., USA

Richard E. Mounce, DDS, is the author of the nonfiction book “Dead Stuck,” “one man's stories of adventure, parenting, and marriage told without heaping platitudes of political correctness.” Pacific Sky Publishing, DeadStuck.com. Dr. Mounce lectures globally and is widely published. He is in private practice in endodontics in Vancouver, Wash. Contact him at [email protected].