Workplace violence: De-escalating tense situations in the dental office

Dental health-care workers face challenges daily where they find themselves dealing with angry, hostile, and undesirable behavior. These situations can easily lead to incidences of workplace violence (WPV) if they are not de-escalated. Our responses to these offensive behaviors play a crucial role in determining the outcome of the situation.1,2 WPV in health-care settings is a pervasive, systemic problem that increases employee turnover and decreases the ability to retain qualified, skilled professionals in the dental practice.2,3

Statistics on workplace violence

The World Medical Association defines workplace violence in health care as “an international emergency that undermines the very foundations of health systems and impacts critically on patients’ health.”2 According to the Society for Human Resources Management,4 one in seven employees in the US workforce feels unsafe in their workplace. Medical and dental providers are five times more likely to experience WPV than all other industries.

Aggressive acts against health-care providers increased by 63% in the decade leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic.5 Prior to the onset of the pandemic in early 2020, 60% of the health-care workforce, including dental professionals, had experienced verbal or physical abuse from a patient.5

In the next two years, that prevalence rose to 89% of the health-care workforce reporting having experienced an event of WPV with a patient, patient’s family member, or colleague at some point in their clinical careers.2 In a nationwide study of medical and dental providers from various specialties, the American Nurses Foundation6 found that 16% of health-care providers were planning to leave their professions and the health-care industry within the next six months due to issues related to WPV.6 Sixty percent of dental professionals have experienced WPV from a patient or coworker. More than half of those (55%) were incidents of verbal abuse: shouting, name-calling, expletive language directed at the employee, or threats to harm the employee.7

Efforts to reduce the risks of WPV

Because employee turnover related to WPV puts more stress and additional work on the remaining staff, which can escalate stress, increase patient wait times, increase clinical mistakes, and lead to even more violence, in 2019 health-care organizations started to internally campaign for reducing the risks of WPV and protecting health-care staff members.2 However, since little guidance and criteria existed on establishing comprehensive and effective programs to address WPV, professional health-care providers and a nursing association started to lobby the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) for mandates, regulations, and standards that specifically address WPV.2

How WPV impacts dental professionals

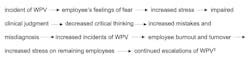

WPV leads to a cascading series of events that negatively impact dental professionals, quality of care, and their organizations.

WPV events wear down the dental provider’s ability to cope and significantly increase symptoms of poor mental health (e.g., anxiety, depression, and PTSD).2 Events of WPV and hostility that occur between members of the dental team erode trust and kill effective communication between coworkers. This creates a tense environment that is visible to other team members and felt by patients. The anxiety and mistakes created by the tension decrease patients’ trust in their dental team.8

Liabilities caused by WPV

Protection from WPV is a large benefit of dental service organizations (DSOs). DSOs have designated human resource professionals who are skilled specifically in addressing these issues that occur with patients and team members. Small or privately owned dental practices have an office manager but may not have a designated human resources manager who is knowledgeable in employment regulations and the full scale of liabilities from failing to protect staff. If an organization or office suspects there is a significant risk to employees and fails to take adequate and fast action, they are opening themselves up to a potential massive litigation.4

Workplace training is essential

To effectively decrease risks for WPV, dental practices need an all-in approach and cultural shift promoting safety and support for all employees.2,4 Practices should provide training for both individuals and small teams of individuals to identify, report, and manage the risks and safety concerns associated with WPV. In groups where staff have received formal training, they report feeling confident to identify situations that could quickly escalate to WPV and feel equipped to intervene in the situation to decrease the risk of escalation and violence. Having trained, confident staff present in the workplace daily also increases employees’ feelings of safety and support.2,4

Patients who repeatedly yell or curse at staff, make threats, or display inappropriate behaviors should be dismissed from the dental practice. Simply transferring these patients to another provider within the same facility allows the patient to continue their aggressive behaviors toward other employees. It further sends a message to staff and providers that their safety is not of paramount concern.

When an employee is the aggressor, practices need to adhere to their standards for employees, as contracts with individual employees or employee unions may outline procedures to follow. Law enforcement should always be contacted immediately if any individual (patient or employee) has assaulted or threatened to assault an employee.9

Crisis Prevention Institute (CPI) is the world’s leading provider of trauma-informed and de-escalation trainings for health-care organizations. For more than 40 years, they have consulted with health-care organizations to implement programs that create a culture where all staff are trained to recognize and prevent WPV. CPI’s programs and trainings are based on evidenced-based research to provide staff with the safest and most effective tools to de-escalate a situation.10

CPI recommends 10 easy techniques to apply for health-care providers who are dealing with challenging behavior.1

Be empathetic and nonjudgmental

You can judge a person’s behaviors, but do not judge the person. Give them your undivided attention and listen carefully to the facts and feelings they express. Reassure them that you want to help. Paraphrase what they said and ask questions to clarify.1,9,11,12

Respect personal space

As dental professionals, we typically work 14 inches from the patient’s face. If the patient seems uncomfortable, push your chair back so that it’s one to three feet away from them. More personal space decreases anxiety, which lowers tempers. If you need to reenter the patient’s personal space, explain your actions prior to moving close so they feel less confused.1,9

Allow time for decisions

When we are upset or stressed, we cannot make well-informed and rational decisions. Angry or aggressive individuals are the same; they cannot think clearly when they’re upset. Give them time to think through their options. Avoid increasing anxiety and stress by allowing them to go home and consider how they want to move forward. This will mean not completing any dental treatment that day, but it’s safer for all parties.1

Use nonthreatening nonverbals

The more a person escalates into distress, the less they can process your verbal instructions, and they become more reactive to your nonverbal communication. Tone and body language should reflect that we respect the patient, even though we do not respect their current behavior. Be mindful of your gestures, facial expressions, tone of voice, and physical movements when working with someone who is in crisis.1,9,11,13

Set limits

When a patient is belligerent or defensive, it’s crucial to establish boundaries of what behaviors will and will not be tolerated. Setting limits is an effective and safe de-escalation technique that clearly defines the boundary, explains expectations of the person based on what is reasonable, and outlines the consequences for crossing that boundary. Limits, when challenged, need to be enforced by the practice’s leadership. These limits are meant to protect staff, rather than punish the aggressive individual.1,11,13

Focus on feelings

When dealing with escalating behaviors, how the person feels is key to their continued behavior. Not all individuals have the emotional intelligence to describe their specific feelings about a situation, so they express those feelings as anger and aggression instead. Listen for the patient’s emotional concerns and acknowledge their feelings.1,9,13

Ignore challenging questions

Frustrated individuals often ask questions to challenge or question our authority. It’s important to redirect their attention to the issue at hand. Engaging them only escalates the situation by creating a power struggle. Dental providers must remain calm and composed so that patients feel like they’re in control of the situation around them.1,11,12

Avoid overreacting

We cannot control the emotions and behaviors of others, but we can and must control our own responses and reactions to the individual and the situation. Remaining calm, rational, and professional will have a direct impact on diffusing the tension.1,11,12

Wisely choose what you insist upon

Be thoughtful and considerate of the patient when deciding which rules and limits are negotiable and which cannot be. Use motivational interviewing techniques to determine what things might help gain the patient’s cooperation and compliance. Demonstrating that you are willing to be flexible and accommodating will help avoid unnecessary confrontations.1,9,11

Allow silence for reflection

It may seem unnecessary to allow for quiet time in a tense situation, but this is often the best choice. It gives you and the patient a chance to reflect on behaviors, nonverbal movements, and the situation at hand. It gives everyone a chance to take some deep breaths and consider how to respond.1,9,11,12

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in Clinical Insights newsletter, a publication of the Endeavor Business Media Dental Group. Read more articles and subscribe.

Resources for WPV prevention

- US Department of Labor

- Society for Human Resource Management

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)

More about dealing with challenging patient behaviors ...

References

- Top 10 de-escalation tips. Crisis Prevention Institute. 2023. https://platform.crisisprevention.com/CPI/media/Media/download/PDF_DT.pdf

- Urbanek KA, Graham KJ. Workplace violence in the health care industry–an introduction. In Urbanek KA, Graham KJ, eds. Workplace Violence Prevention Handbook for Healthcare Professionals. Crisis Prevention Institute; 2022:1-12.

- Norful AA, Rosenfeld A, Schroeder K, Travers JL, Aliya S. Primary drivers and psychological manifestations of stress in frontline healthcare workforce during the initial COVID-19 outbreak in the United States. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021;69:20-26. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.01.001

- Understanding workplace violence prevention and response. Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). 2019. https://www.shrm.org/topics-tools/tools/toolkits/understanding-workplace-violence-prevention-response

- Boyle P. Threats against health care workers are rising. Here’s how hospitals are protecting their staffs. Association of American Medical Colleges. August 18, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/news/threats-against-health-care-workers-are-rising-heres-how-hospitals-are-protecting-their-staffs

- Berlin G, Burns F, Hanley A, Herbig B, Judge K, Murphy M. Understanding and prioritizing nurses’ mental health and well-being. American Nurses Foundation. McKinsey & Company. November 2023. https://www.nursingworld.org/~4aaf68/contentassets/ce8e88bd395b4aa38a3ccb583733d6a3/understanding-and-prioritizing-nurses-mental-health-and-well-being.pdf

- Binmadi NO, Alblowi JA. Prevalance and policy of occupational violence against oral healthcare workers: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19(1):279. doi:10.1186/s12903-019-0974-3

- Rehder KJ, Adair KC, Hadley A, et al. Association between a new disruptive behaviors scale and teamwork, patient safety, and work-life balance, burnout, and depression. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2020;46(1):18-26. doi:10.1016/j.jcjq.2019.09.004

- Shannon JW. Reasoning with unreasonable people: focus on disorders of emotional regulation. Presentation and lecture notes. Institute for Brain Potential; June 18, 2022.

- CPI training for health care facilities. Crisis Prevention Institute. 2021. https://www.crisisprevention.com/industries/health-care/

- Thompson GJ, Jenkins JB. Verbal Judo: The Gentle Art of Persuasion. Blackstone Publishing; 2017.

- Zarefsky D. The Practice of Argumentation: Effective Reasoning in Communication. Cambridge University Press; 2019.

- Sullivan AO. (2011). The importance of effective listening skills: implications for the workplace and dealing with difficult people. Master’s thesis. All Student Scholarship. University of Southern Maine. 2011. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/etd/11/

Kimberly A. Erdman, MSDH, RDH, FAADH, FADHA. is a practicing dental hygienist and public health dental hygiene practitioner. She was a civilian-dental hygienist for the U.S. Navy and spent nine years as a forensic dental technician. She has a decade of experience in higher education and administration. Kimberly has been awarded a fellowship with the American Academy of Dental Hygiene and the American Dental Hygienists’ Association.

About the Author

Kimberly A. Erdman, EdD, RDH, FAADH, FADHA

Kimberly A. Erdman, EdD, RDH, FAADH, FADHA, is a dental hygienist at Aspen Dental, as well as a PhD Methodologist at Liberty University. She loves providing top-notch patient care while also being able to teach and mentor students pursuing graduate health science work. Kimberly is a proud member and Inaugural Fellow of the American Dental Hygienists’ Association and a Fellow of the American Academy of Dental Hygiene.