Focus on Dental Caries Management

The Remineralization Challenge

The first part of our series addressed basic management of caries, allowing the woman dentist to integrate prevention and treatment into minimally invasive caries management and control for patients. This article, Part 2, focuses on the emerging medical model for managing caries with early intervention aimed at remineralizing or halting further cavitation of the lesion, combined with new diagnostic techniques. We include resources for stimulating remineralization so that you can provide the best preventive practice for your patients. This philosophy of practice expands into the medical model of disease prevention linked to care. While traditionally, dental professionals are skilled in diagnosing cavitated lesions, Anderson has stated that decay removal alone (e.g., burs, lasers, etc.) is analogous to surgically removing diseased lung tissue without treating the Mycobacteria tuberculosis bacteria.1

Prognosis and diagnosis of caries are two essential steps in managing caries. We now have new tools for detection of caries at an earlier stage than was possible with our traditional technology (mirror, explorer in a dry field with good lighting, and radiographs). These detection devices are not 100 percent accurate, but when used in combination with clinical judgment, they result in earlier diagnosis of dental caries. Woman Dentist Journal has focused on two of these detection devices — DIAGNOdent in the November/December 2003 issue, and QLF in the September/October 2003 issue.2 Prognosis is also a critical step in determining treatment in this medical model management. Prognosis is simply the likelihood of further cavitation or remineralization. The prognosis of the lesion will also help determine whether to treat surgically by excavation, or with medical management using specific products, such as fluoride, xylitol, or antimicrobial products.3

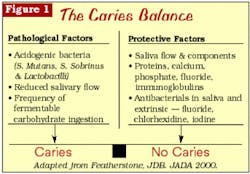

Two key issues are important in understanding the caries process. First, caries is a bacterial infection caused by specific bacteria, generally Streptococcus mutans in the early stage and Lactobacillus acidophilus in later stages.4 The bacterial load cannot be reduced by the placement of restorations.5 The bacterial load can be reduced by specific techniques and processes, remembering that the bacteria behave differently in a biofilm on the tooth surface. Secondly, caries can best be described as a reversible multifactoral process. Destructive factors for caries include bacteria and carbohydrate intake, while protective factors include salivary flow, enhanced salivary fluoride levels, or antimicrobials in combination with a review of pertinent medical and dental history. One then considers caries as a balance between these destructive and protective factors (Figure 1).6 This is where diagnosis is a critical endpoint.7

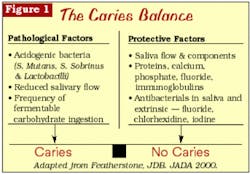

The process of demineralization and remineralization on a specific tooth is described as caries activity. Active lesions are demineralizing, and inactive lesions are remineralizing or remaining static. Rather than a straight-line progression from demineralization to cavitation, we now understand that there are periods of demineralization and remineralization, depending upon the environment around the lesion. If there is an increase in acidity that will dissolve the hydroxyapatite crystal, then demineralization will begin.8 Reversibility of demineralized areas may occur, especially with the aid of barrier factors such as fluoride. Remineralization will occur if the pH is neutral and there is a high mineral concentration — especially calcium, phosphate, and fluoride — in the area. Diagnosis of white-spot lesions is key, with chalky and rough white-spot lesions considered active. Inactive lesions have a smooth surface and sometimes may be stained (Figure 2).9,10,11,12,13

Caries risk assessment addresses the caries status of the patient, including the likelihood of new decay. A caries risk assessment program named CAMBRA (or caries management by risk assessment) is useful. The protocol is user-friendly and easy to implement. It is available to view or download at www.cdafoundation.org/ journal.14 Factors that lower the risk of a future carious lesion are normal salivary flow and high levels of fluoride. Salivary flow below 0.7 ml/minute is considered a risk factor. Other risk factors are past caries history, location of lesion, and medical conditions. Steinberg notes that saliva buffering can reverse the low pH in the plaque, and with the raised pH, calcium and phosphate are driven back into the tooth, remineralizing it. The key is the integrity of the tooth surface.

In clinical practice, women dentists combine caries activity and risk assessment intuitively. To formalize this, consider the four-step medical model adapted from Steinberg:3

- Removal of bacterially infected tooth tissue

- Reducing risk for a patient (decreased ingestion of sugars and carbohydrates, etc.)

- Reversal of demineralization by specific therapy

- Follow-up at home and with office visits (frequency is based upon risk)

We will devote Part 3 of this series to Item 1, the removal of bacterially infected tooth tissue. In that article, we will examine the concept of minimal intervention and how we can remove only the infected tooth tissue. The remainder of this article will focus on Items 2, 3, and 4 — reducing risk, reversal of demineralization, and customized at-home and in-office interventions to promote demineralization.

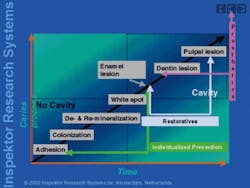

New diagnostic techniques to help monitor de/remineralization balance

As described in Part I, the delicate balance between demineralization and remineralization of teeth occurs continuously, with some reversibility. Our clinical goal is to promote remineralization of these early lesions. There are a number of promising new devices that will allow you to monitor the progression of these early lesions. But at the present time, there is no one device that can accurately measure, monitor, and assess the status of the lesions. Some of the devices can act as an additional tool, but they cannot provide a definitive measure of the lesions.

Figure 3 outlines some of the devices currently available or under development. Now, instead of watching a lesion increase in size (watch and wait to decay?), new diagnostic techniques allow you to measure demineralization, as well as changes in remineralization, much more accurately than current techniques of visual exam or radiograph alone. Today's array of new in-office and at-home products for enhancing remineralization offer the opportunity to track changes in demineralized teeth over time. They may also allow you to visually share the results with patients as a form of motivation.

Caries intervention in your practice

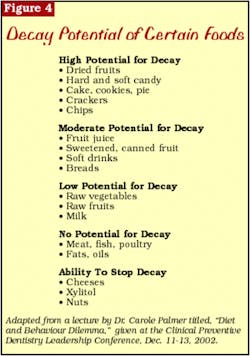

The goal of the dental professional is to increase the protective factors and to disrupt the demineralization cycle. You can also encourage your patients to decrease sugars, especially those in soft drinks. Educate your patients about soft drinks, and let them know about the Web site for the "Stop the Pop" campaign: www.modental.org. Diet analysis and diet control become key issues in stopping demineralization. This not only involves eliminating foods that bacteria can metabolize, but examining when the exposure to these foods occurs. For example, a single can of diet pop consumed once a week is not as destructive as a single candy sucked slowly over one hour each day. It is both the composition and exposure time that makes foods cariogenic. Cariogenic snacks are much worse than cariogenic foods consumed during the course of a meal, especially if the patient brushes after the meal. Figure 4 summarizes the decay potential of various foods.

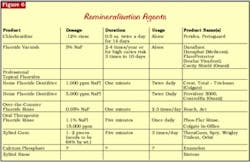

Remineralization can be promoted through a variety of techniques (Figures 5 and 6).15,16,17,18 Recommend fluoride for all patients, not just children. Consider the benefits of a fluoride needs assessment. Oral-B offers a complete patient survey form to assess fluoride exposure.

Customize fluoride recommendations for your patients, depending on risk assessment. Fluoride has three main mechanisms of action:

- It inhibits metabolism of bacteria, such as S. mutans, metabolis.

- It inhibits demineralization.

- It enhances remineralization.20

Application choices may be topical or prescribed rinses (see Figure 6). Provide topical fluoride for patients on a regular basis based on their particular caries risk.

One successful antibacterial therapy for cariogenic bacteria is chlorhexidine rinses. By prescribing a twice-daily, two-week, 0.12 percent chlorhexidine rinse regimen, the cariogenic bacteria can be reduced significantly.

Fluoride varnish is yet another preventive tool. It is a concentrated fluoride dispensed in single-dose delivery or in a tube. It has excellent adherence qualities to the tooth surface — whether applied wet or dry — and is very effective, particularly around orthodontic brackets and erupting molars.21 Clinical trials involving fluoride varnishes show caries incidence reduction ranging from 18 to 70 percent.22

Saliva, especially the amount and flow, is critical in the remineralization/demineralization balance. Saliva and its buffering contents deliver the needed minerals for the repair process of the tooth surface. An excellent mouthwash is Biotene. It contains no alcohol and has xylitol. Also note that gum chewing — particularly brands containing xylitol — will stimulate the flow of saliva. Recommend toothpastes containing baking soda for the saliva-deficient patient. For improved hydration, add two teaspoons of baking soda for each eight ounces of water. Instruct patients to swish frequently throughout the day. The baking soda will increase the available mineral content in saliva and thus help to promote remineralization. Watch the medications that your patients are taking and monitor their medical health. A slight change in saliva production, even if it's induced by medication, may be enough to increase their risk for caries.

Therapeutic gum chewing has been shown to be effective in reducing the transmissibility of the infectious bacteria that cause decay.23,24 The five-carbon sugar substitute xylitol is yet another protective factor found in chewing gum and rinses. Xylitol has several benefits:

- Reduced caries and plaque

- Decreased cariogenic bacteria25

- Enhanced remineralization

- Increased salivary flow26

Patients will receive xylitol's benefit by chewing gum (64 percent by weight) three times per day for a minimum of five minutes. Obviously, brands that contain xylitol at the top of their ingredient list are more efficacious.

The challenge

Caries research and methodology are moving forward to detect the earliest bacterial involvement and tooth surface changes. Dental professionals need to embrace current and proven preventive and preservative treatment modalities. In essence, partner with your patients to promote elevated diagnostic awareness, provide caries risk assessment, and commit to remineralization balance.

Part 3 of this series will examine the technique, materials, and concept of minimal intervention for the restoration of carious lesions.

References

Lori Trost, DMD

Dr. Trost is the managing editor of Woman Dentist Journal. She created the Center for Contemporary Dentistry in Columbia, Ill., in 1989. Her practice is known for being in the technological forefront. She is a member of the ADA and AGD.You may contact Dr. Trost at [email protected].

Margaret I. Scarlett, DMD

Dr. Scarlett is the science and women's health editor of Woman Dentist Journal. An accomplished clinician, scientist, and lecturer, she is retired from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. You may contact her by email at megscarlett@ mindspring.com.

Stephen H. Abrams, DDS

Dr. Abrams is a partner in a group practice in Toronto, Canada. He is collaborating on the development of a laser-based system for caries diagnosis. He founded Four Cell Consulting which provides advice to dental manufacturers. Contact him at dr.abrams [email protected].