Because of the demands of our caregiving roles, women in dentistry frequently ignore their own skin care. Healthy skin is a vital barrier against damage from abrasion, chemical irritants, and infectious agents. So choose your hand-care products and practices carefully.

As caregivers at home and in the office, women can be up to their proverbial elbows in soaps, disinfectants, lotions, and powders. We frequently take our hand and fingernail care for granted, ignoring dryness and cracking, or burning sensations when using chemicals. I was reminded of this while browsing a recent issue of the American Journal of Infection Control (AJIC). In it, I read about a health-care worker who, because of her chronically abraded skin and poor personal protection, had been infected with HIV and HCV.1 Even without a needlestick or sharps injury, these deadly viruses had been transmitted past the worker's broken skin barrier.

In providing dental care, it is essential that we take care of our skin, particularly the skin exposed in patient care. But how do we balance the demands of dentistry, home, and caregiving with the need for proper hand hygiene? The goal of this article is to highlight common pitfalls and provide some simple solutions.

With our bare hands

Women dentists wash their hands often, probably 30 times a day or more, assuming at least two handwashings per patient. Although this is an integral part of infection control in dentistry, harsh handwashing practices can damage healthy skin. Soaps, while necessary to remove dirt and body fluids, can deplete the skin's lipid content and alter its pH. Overly abrasive handwashing can physically strip protective cell layers. Both undermine the skin's basic barrier function and provide opportunity for infection, irritation, or allergy.2 It's not surprising that hand dermatitis problems plague at least a quarter of health-care workers.3

Although we may not recognize it, a woman's skin is exposed to hundreds of chemicals throughout the day. One glance at the ingredients list from our hand lotions, soaps, disinfectants, cleaners, and dental chemicals will affirm this fact. Some substances can be irritating — like soap or chlorine bleach. Others are allergens common in dental and consumer products, such as disinfectants (chlorhexidine and glutaraldehyde), fragrances, dyes, antiseptics, preservatives, and even metals (nickel and gold jewelry).3,4

Like nicely coiffed hair, women may feel that artificial fingernails greatly improve their appearance. However, artificial fingernails also provide a safe haven for pathogens.5 As dentists, we demand clean gingival margins to prevent periodontal disease. But paradoxically, we tolerate the dirty "margins" that develop around artificial fingernails. Just imagine the legions of bacteria harbored in the pits and fissures common to artificial fingernails!

For women dental professionals, artificial fingernails create another unique problem. Both nail glue and dental bonding agents contain similar chemicals, known as methacrylates. Those who wear artificial fingernails and use bonding agents are frequently exposed to the unpolymerized form of these chemicals, which are potent allergens and neurotoxins.6 Dental professionals may develop tingling in their fingers from damaged nerves, as well as cracked and bleeding fingertips from the allergy.

Gloves and gauntlets

What about the gloves we wear? As the AJIC case report reminds us, we should never assume medical gloves could replace a healthy, intact skin barrier. Despite our preconceptions, even the best medical gloves can fail during use due to chemical or physical stress.7 Long fingernails and finger rings can also contribute to premature glove failure and increase pathogen load on health-care workers' hands.5,8 Some dental chemicals, such as methacrylates, easily permeate thin medical gloves.9 Gloves are not impervious gauntlets; they are only a thin rubber shield designed to limit pathogen exposure.

Many dentists are also unaware that natural and synthetic rubber gloves contain various chemicals added during their manufacture. Some of these chemical additives — such as thiurams and carbamates — are strong allergens. Unfortunately, as with fragrances and preservatives, these chemicals can be found in other products besides gloves.10 For women dental professionals allergic to these rubber-based chemicals, their use in over-the-counter cosmetic or horticultural products can be especially problematic.

Handy solutions for skin

We must implement better skin care and hand hygiene regimens for our colleagues and ourselves. The soaps we select (either plain or antibacterial) should be nonirritating with a neutral pH, and contain an emollient to reduce dryness. The new dental infection-control guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention permit use of alcohol-based hand rubs if hands are not visibly soiled.11 Alcohol hand rubs can improve hand hygiene compliance and reduce pathogen load. Their use has also been shown to improve skin condition and reduce dryness.12

We should use lotions and creams sparingly at work. These products add another layer of chemicals to our skin under the glove, including fragrances and preservatives. Unfortunately, controlled testing is rarely performed with these over-the-counter products. In the studies performed to date, most lotions and creams have little effect, but some actually worsen skin condition.13 Remember also that containers of these hand-care products, like liquid soaps, must be protected from possible microbial contamination. The new infection-control guidelines recommend that hand-care product containers be regularly replaced or thoroughly cleaned.11

Choose medical gloves based on comfort, fit, in-use performance, and user needs. While it is difficult to predict glove performance, a poorly fitted, uncomfortable glove is more likely to break or tear, undermining its ability to protect. Valid needs and preferences include ease of donning, surface coatings, or textures — all of which can influence comfort and ease of use. Selecting an appropriate glove material can also be critical for managing rubber-based allergies. Unfortunately, price is usually the sole criteria for glove selection. Therefore, it's important to consider that gloves manufactured with stricter quality control guidelines can be more consistent in quality and well worth the expense.

Summary

Because of the demands of our caregiving roles, women in dentistry frequently ignore their own skin care. At dental conferences, I have seen the red, peeling, and deeply cracked skin of my female colleagues. They forget that healthy skin is a vital barrier against damage from abrasion, chemical irritants, and infectious agents. Gloves or other barriers cannot replace it. More importantly, poor skin care can be an initiating factor in occupational skin disease.

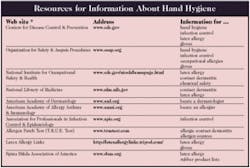

Therefore, just as you choose nutritious food and exercise, select hand-care products and practices that are good for your skin. Avoid wearing jewelry and artificial fingernails in the dental treatment room. Opt for medical gloves that meet all your needs, not just the minimum requirements. Educate yourself about the different chemicals in the dental office and how to use them properly. Minimize the abuse your skin endures at home, in the garden, or in recreation. Be mindful of activities that can increase your skin's exposure to pathogens or chemicals. And finally, if skin problems do develop, find a dermatologist or allergist quickly who can provide a solution based on a thorough diagnosis.

References

- Beltrami EM, Kozak A, Williams IT, et al. Transmission of HIV and hepatitis C virus from a nursing home patient to a health-care worker. Am J Infect Control 2003; 31:168-75.

- Larson E. Hygiene of the skin: when is clean too clean? Emerg Infect Dis 2001; 7:225-30.

- Holness DL, Mace SR. Results of evaluating health-care workers with prick and patch testing. Am J Contact Dermatitis 2001; 12:88-92.

- Kucenic MJ, Belsito DV. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis is more prevalent than irritant contact dermatitis: a 5-year study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 46:695-9.

- Jeanes A, Green J. Nail art: a review of current infection-control issues. J Hosp Infect 2001; 49:139-42.

- Kanerva L. Cross-reactions of multifunctional methacrylates and acrylates. Acta Odontol Scand 2001; 59:320-329.

- Albin MS, Bunegin L, Duke ES, et al. Anatomy of a defective barrier: sequential glove leak detection in a surgical and dental environment. Crit Care Med 1992; 20:170-84.

- Trick WE, Vernon MO, Hayes RA, et al. Impact of ring wearing on hand contamination and comparison of hand hygiene agents in a hospital. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 36:1383-90.

- Munksgaard EC. Permeability of protective gloves by HEMA and TEGDMA in the presence of solvents. Acta Odontol Scand 2000; 58:57-62.

- Fisher AA, Rietschel RL, Fowler JF, Jr. Allergy to rubber. In Fisher's Contact Dermatitis, 2000; 5th edition:533-60.

- Boyce JM, Pittet D. Guideline for hand hygiene in health-care settings: recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002; 51:1-50.

- Pittet D. Improving adherence to hand hygiene practice: a multidisciplinary approach. Emerg Infect Dis 2001; 7:234-40.

- Baur X, Chen Z, Allmers H, et al. Results of wearing test with two different latex gloves with and without the use of skin-protection cream. Allergy 1998; 53:441-44.

Beth Hamann, DDS

Dr. Hamann serves as vice president of SmartHealth and practices dentistry part-time. As a community leader, she developed 'Hands of Hope,' a Central American dental-medical outreach program. She consults and speaks on issues important to women in dentistry. Contact her at [email protected].

Pamela A. Rodgers, PhD

Dr. Rodgers writes about disease prevention and occupational health in dentistry and medicine, supporting SmartHealth's corporate mission to improve health-care practice. She also helps coordinate SmartHealth's research programs investigating patient communication, infection control, and occupational health. Dr. Rodgers is passionate about fostering education and professional development for women in the sciences. Contact her at [email protected].