Peri-implant diseases: Professional interventions

Professional management of dental implants can involve a variety of procedures, namely mechanical and chemical. These may include hand instruments, ultrasonic and sonic instruments, air abrasive systems, lasers, antibiotics, and antimicrobials. It is vital to prevent disease around a healthy implant, and to prevent peri-implant mucositis from becoming peri-implantitis. This article will outline some of these modalities.

As with any appointment, we must follow the process of care: assessment, diagnosis, treatment planning, implementation, evaluation, and documentation. A detailed medical and dental history will reveal any systemic conditions or lifestyle habits that may affect the patient. We should assess for risk, prognostic, and predictive factors. (1) We are most concerned with prognostic factors, like smoking. We should counsel patients about modifiable prognostic factors such as smoking, diet, oral hygiene, and professional maintenance. Maintenance is considered a positive prognostic factor. (1)

READ MORE |Understanding and managing peri-implant bone loss

Examination protocols

A visual examination should include the construction of implants, changes in the soft tissue around implants, and oral hygiene status. Clinical examination should check for mobility of the suprastructure, abutment, or implant; bleeding on probing (BOP) or suppuration; and pocket depths (PD). The significance of peri-implant probing is well documented in the literature. (2) You need at least two points to compare when considering probing. One protocol might be baseline, 6-12 weeks after the prosthetic is placed, at one year, then at three years. (3) Radiographs should be taken, but show past history and not prognosis. If inflammation is present, Dr. Fardal suggested increasing the frequency of professional care, microbial testing; local or systemic microbial therapy, and modification of negative life style factors. (1)

Instrument options

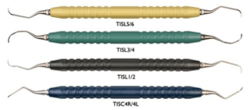

In the treatment phase, we can use manual, ultrasonic, sonic, or other types of treatments. Hand instruments come in a variety of materials, including plastic, titanium, graphite, and PLASTEEL (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL). Metal instruments are effective in decreasing bacterial biofilm, but may result in scratches on the surface of titanium implants. Other materials may result in less harm to the implant surface, but can be less efficient. (2) There are also a number of non-metal probes available. See Table 1 for some examples.

Table 1: Hand instruments

Ultrasonic and sonic instruments can also be used for implant maintenance. One study showed the efficacy of using ultrasonic devices for reducing bacterial plaque biofilm and bleeding scores. (4) Other studies have shown similar results. Air abrasive systems use sodium bicarbonate, sodium hydrocarbonate, calcium phosphate, amino acid glycine, and erythritol-chlorhexidine. Most are efficient at biofilm reduction.

Table 2 below is a partial list of products.

Table 2: Ultrasonic and sonic instruments

Lasers, antibiotics, and photodynamic therapy

Lasers are also used for implant maintenance (e.g., diode lasers, Nd:YAG, Er:YAG, CO2 lasers). Encouraging results have also been detected with the Er:YAG laser in the treatment of peri-implantitis, and it is the most popular choice at present. (2) Locally-administered antibiotics have been shown to be useful as adjunctive therapy to mechanical debridement, particularly the controlled release systems. Systemic antibiotics increase the antimicrobial level in the peri-implant crevicular fluid. (2) A 2008 review showed that adjunctive local or systemic antibiotics were shown to reduce bleeding on probing and probing depths.(5) Negligible beneficial effects of laser therapy on peri-implantitis have been shown, and needs further research. (5) A systematic review proposed that submucosal debridement with adjunctive local delivery of antibiotics, submucosal glycine powder air polishing, or Er:YAG laser treatment could decrease clinical signs of peri-implant mucosal inflammation, as compared to submucosal debridement using curettes with adjunctive irrigation with chlorhexidine. (6) One paper showed that photodynamic therapy may be an option for reducing bacteria on implant surfaces. (7) Laser irradiation by itself, without the association of dye, was less efficient than photodynamic therapy (PDT). (7)

READ MORE |Recommendations from the European Federation of Periodontology

For peri-implantitis, non-surgical mechanical debridement with adjunctive use of PDT is just as effective in the reduction of mucosal inflammation as with the adjunctive use of minocycline microspheres up to 6 months. (8) PDT as an adjunctive therapy could be an alternate treatment choice. for the non-surgical management of initial peri-implantitis. However, none of the adjunctive therapies achieved complete resolution of inflammation. (8) That being said, according to some, the only treatment that appears effective at resolving peri-implantitis appears to be surgical therapy. (9)

Peri-implant mucositis is reversible and treatable, but of the few high quality studies found on this topic, none reported complete treatment of the patient. There is a need for stronger evidence, followed by an evidence-based protocol for clinical treatment. Treating the disease at a mucosal level may help progression to bone destruction.

The primary goal in the prevention of peri-implant disease is elimination of the biofilm from the implant surface. Nonsurgical therapy is a frequently used treatment, along with various adjunctive therapies. (10) The current evidence supports that peri-implant mucositis is reversible when correctly treated. Mechanical therapy with local antimicrobials as an adjunctive aid may also be considered as an alternative to surgical intervention when treating peri-implantitis in cases not appropriate for surgery. (10) The bottom line, regardless of the therapy used, is the ability of the patient to maintain good oral hygiene. (10)

References

1. O Fardal. EuroPerio8 session. Critical Factors in the Assessment of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Disease. Prognostic factors for the long term success for the Periodontal/Peri-implant patient. Friday June 5, 2015, 10:30 – 12:00.

2. Wang Y, Zhang Y, Miron RJ. Health, Maintenance, and Recovery of Soft Tissues around Implants [published online April 15, 2015]. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. doi: 10.1111/cid.12343.

3. D Barendregt. EuroPerio8 session. Critical Factors in the Assessment of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Disease. Clinical Diagnostic Methods in Periodontal and Peri-Implant Disease, Friday June 5, 2015, 10:30 – 12:00.

4. Renvert S, Samuelsson E, Lindahl C, Persson GR. Mechanical non-surgical treatment of peri-implantitis: a doubleblind randomized longitudinal clinical study. I: clinical results. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:604–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01421.x.

5. Renvert S, Roos-Jansåker A, Claffey N. Non-surgical treatment of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis: a literature review. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(suppl 8):305-15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01276.x.

6. Muthukuru M, Zainvi A, Esplugues EO, Flemming TF. Non-surgical therapy for the management of peri-implantitis: a systematic review. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23(suppl 6):77-83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2012.02542.x.

7. Marotti J, Tortamano P, Cai S, Ribeiro MS, Franco JE, de Campos TT. Decontamination of dental implant surfaces by means of photodynamic therapy [published online July 12, 2012]. Lasers Med Sci. 2013;28:303–309. doi:. 10.1007/s10103-012-1148-6.

8. Schär D, Ramseier CA, Eick S, Arweiler NB, Sculean A, Salvi GE. Anti-infective therapy of peri-implantitis with adjunctive local drug delivery or photodynamic therapy: six-month outcomes of a prospective randomized clinical trial [published online May 9, 2012]. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2013;24:104-10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2012.02494.x.

9. Nicolucci M. Peri-Implantitis: Treatment Options. Oral Health Journal. http://www.oralhealthgroup.com/news/peri-implantitis-treatment-options/1002516513/?type=Print%20Archives. Published August 1, 2013. Accessed June 16, 2015.