Protecting the oral cavity and mind of type II diabetics: The comorbidity of type II diabetes, Alzheimer’s, and periodontitis

Those with diabetes and forms of dementia face their own oral health challenges. There has long been a connection between type II diabetes and Alzheimer's; recent research suggests that Alzheimer's may actually be a form of diabetes itself. In this article, learn about the mechanisms of periodontitis in those with diabetes and Alzheimer's, as well as useful patient care considerations.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) affects approximately 5 million Americans and is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States (1, 2). The United States is expected to have 16 million cases of AD by the year 2050 (3). There is currently no known cure for AD because there is no known cause of the disease; this lack of information prompted researchers to investigate the possible link between type II diabetes mellitus (DM) and AD (4). Research shows a direct correlation between increased blood glucose levels and inflammation of the tissues around the teeth. Additional research reveals that patients suffering from AD are also at an increased risk of developing periodontitis.

History

The hypothesis for “type III diabetes” (i.e., that AD is the third type of diabetes) was developed in 2005 with research from Brown University (5). This research is relatively new and does not give a conclusive link. Although the research is new, the concept of this theory has been around since the 1990s. The 1998 Rotterdam Study recognized the potential link between diabetes and AD (5). The study found a pattern in the subjects. A high percentage of the elderly people who developed AD were already diagnosed with type II DM, and research is showing an increased incidence in periodontitis with these diseases. This realization has led to current research being performed today.

Periodontitis

Periodontitis is a chronic disease of the tissues that support the teeth that is caused by gram negative bacteria colonizing the oral cavity beneath a patient’s gingiva (6). This results in destruction of the bone supporting the teeth, recession of gingival tissue, and possible tooth mobility. There is no cure for periodontal disease, but treatment can be performed to halt or correct some of the loss of bone or gingiva. If periodontitis progresses without intervention, teeth could be lost. The bacteria surrounding the teeth thrive off of glucose, and patients with type II DM have an increased amount of glucose in the fluid is secreted from gingival tissues (7). The increase of glucose in the fluid provides a great source of nutrition for the destructive bacteria, allowing them to grow and multiply, causing further loss of bone (7).

Patients who are suffering from AD are also at an increased risk of periodontal diseases including gingivitis and periodontitis because of a lack of oral care (8). The patients will oftentimes forget to brush their teeth, and in the later stages might require assistance from a care giver (8). Caring for the oral cavity of these patients can be challenging because the patients become combative or do not like the sensation of having routine professional care (8). Also, in the advanced stages of AD, caring for these patients in a dental clinic can be challenging. The families or caregivers might not bring the patients in to the dental clinic to be treated because getting them to the clinic can be difficult. Without professional removal of the debris from the oral cavity, the disease will continue to progress and lead to possible tooth loss (8).

READ MORE | Basic care for periodontal disease may not be enough for patients with diabetes

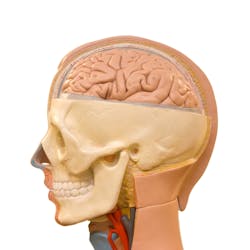

Alzheimer’s disease

While the readers may have a thorough understanding of diabetes and its complications, it is vital to have an adequate comprehension of AD as well. AD is a degenerative brain disorder that gradually destroys the ability to remember, reason, learn, and imagine (9). AD is seen in three stages related to progression. Stage one is considered to be the early/mild stage of the disease. The symptoms of this stage are noticed in conversation with increased forgetfulness and losing everyday objects (10, 11). Stage two is the middle/moderate stage. This is the longest stage where the individual has difficulty with communication and loses direction easily (10). Individuals with AD exhibit changes in mood and behavior along with feeling confused and disoriented. Stage three is the severe/late stage of AD. In this stage, the individual will exhibit difficulty swallowing, walking, and speaking (10). Although there is no current cure for AD, there are some prevention strategies that can be implemented to reduce the risk of developing AD. These include regular exercise, mind-stimulating activities, and diet modifications (12). Medication can be given to slow the progression of AD once diagnosed, but a cure does not exist.

Diabetes

Individuals developing type II DM later to midlife are at an increased risk for developing AD (5). Type I diabetics are typically diagnosed early in their lifetime. They exhibit more control of their blood glucose levels because they require insulin injections. Insulin and blood glucose are more stable when monitored closely in type I diabetic patients, therefore, individuals with type I DM are less likely to develop AD (14).

Type II diabetics are at an increased risk for becoming hyperglycemic. Hyperglycemia increases oxidative stress (5). The increased oxidative damage will compromise the endothelial lining of the cerebral blood vessels and neurotoxins are released, which will decrease acetylcholine production (5). Acetylcholine is one of the most abundant neurotransmitters in the human body. This chemical messenger sends signals from synapses from one neuron to another until the target neuron is reached.

Decreased acetylcholine production and comprised endothelial linings encourage the formation of deadly beta-amyloid plaques (5). These beta-amyloid plaques accumulate in the brain and cause normal neurofirbin to tangle. The neurofibrillary tangles deteriorate the white matter of the brain and exacerbate diabetes by killing the beta islet cells of the pancreas (5).

READ MORE | Periodontal disease and poor dental health may be an early sign of Alzheimer's disease

Dental considerations

Oral care for patients with AD is usually lacking or forgotten altogether in the later stages (9, 10). Poorly controlled diabetic patients are at an increased risk of tooth loss (7). When both type II DM and AD are present in an individual, the risk for developing periodontitis increases. To prevent development or progression of periodontitis, it is important that these patients have a dental home and receive routine preventive care. Patients with periodontitis will need to have periodontal treatment at their dental office every three to four months (6,7,8).

Besides preventing and treating periodontitis, diabetic patients are at increased risk of developing other oral complications. One common complication with diabetic patients is xerostomia caused by medications or uncontrolled diabetes. The gold standard for alleviating xerostomia is frequent sipping of water. Patients with xerostomia can also use products to alleviate symptoms of dry mouth, such as rinses, gums, gels, or suck on frozen grapes. Patients with xerostomia should also avoid acidic foods and beverages or rinse the mouth with water immediately after consuming these (6). When patients do not have adequate salivary flow, acid is not neutralized as quickly in the mouth. The lower pH in the oral cavity causes enamel erosion and a favorable environment for pathogenic bacteria to grow and thrive (6). Along with the low pH, elevated glucose levels will further increase the risk of caries.

Diabetics experience a prolonged healing time throughout the body, including the mouth. Decreased circulation of blood prevents nutrients and white blood cells from reaching any site of infection (15). This causes a deficiency in how well the immune system functions leading to more infections throughout the body including those surrounding the teeth. Hyperglycemia also impairs the function of immune cells, which aid in the fighting infection (15).

Interventions

As with all areas of health, educating patients about their disease is a top priority. Patients with type II DM should receive an explanation of the risk of developing both AD and periodontitis. They can reduce or eliminate the risk factors by controlling their diabetes through weight loss, diet, and medication (16). Patients should be made aware that neither AD nor periodontitis are reversible, which hopefully will put emphasis on making healthier lifestyle choices (8).

Conclusion

Recent research shows a direct correlation between periodontitis and type II DM, and a strong relationship between type II DM and AD. Individuals with diabetes should strive to prevent the development of periodontitis since they do not heal properly. Once periodontitis is established in a diabetic patient, good control of glucose levels is critical to halt the progression of periodontitis (7, 15). Patients with type II DM and the comorbidity of AD have a higher risk of developing periodontitis. Patients with both type II DM and AD may forget how to provide daily care to the mouth (7, 8). It is important that these patients and their caregivers are made aware of their risk factors, and what they can do to protect their mind and teeth. Diabetes patients need to strive for good control of their disease to prevent the development of AD that results from the development of tangles in the neural networks. Damage to the brain will inevitably cause even more harm to the insulin-producing beta islet cells of the pancreas (5). Even though research has been conducted, further research is still needed to show that there is a conclusive link between type II DM and the development of AD, referred to as type III diabetes (4).

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Emily Holt for her guidance throughout the writing and publishing process.

Editor's note: This article first appeared in RDH eVillage. Click here to subscribe.

Tiffany Kong, RDH, BS, EFDA, is a magna cum laude graduate from the University of Southern Indiana’s dental hygiene program. She served as the vice president of the Chinese Club, secretary of the ADHA Student Chapter, and secretary of Alpha Mu Gamma Foreign Language Honors Society. After receiving her licensure, Tiffany accepted a job at Downtown Dental Spa located in Bloomington, Indiana. In her free time, Tiffany is devoted Yelp Elite member, documenting good foods from her traveling.

For the most current dental headlines, click here.

References

1. Whiteman H. Alzheimer’s disease: are we close to finding a cure? Medical News Today website. http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/281331.php. Published August 20, 2014. Accessed March 1, 2015.

2. 2015 Alzheimer’s disease quick facts. Alzheimer’s Association website. http://www.alz.org/facts/overview.asp. Accessed March 1, 2015.

3. What is Alzheimer’s disease? UsAgainstAlzheimer’s website. http://www.usagainstalzheimers.org/crisis?gclid=COfI0oGRwcQCFbPm7AodqRAAbA. Accessed March 1, 2015.

4. Park SA. A common pathogenic mechanism linking type-2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease: evidence from animal models. J Clin Neurol. 2011;7(1):10-8. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2011.7.1.10.

5.Hammaker BG. More than a Coincidence: Could Alzheimer’s Disease Actually Be Type 3 Diabetes? ADHA. 2014; 28(9):16-18.

6. Roger P, Delettre J, Bouix M, Béal C. Characterization of Streptococcus salivarius growth and maintenance in artificial saliva. J Appl Microbiol. 2011;11(3):631-641. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05077.x.

7. Pérez-Losada FL, Jané-Salas E, Sabater-Recolons MM, Estrugo-Devesa A, Segura-Egea JJ, López-López J. Correlation between periodontal disease management and metabolic control of type 2 diabetes mellitus. A systematic literature review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2016;21(4):e440-6. doi: 10.4317/medoral.21048.

8. Ide M, Harris M, Stevens A, et al. Periodontitis and Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151081.

9. Saavedra JM. Evidence to Consider Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers for Treatment of Early Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2016;362):259-79. doi: 10.1007/s10571-015-0327-y.

10. Stages of Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer’s association website. http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_stages_of_alzheimers.asp. Accessed March 21, 2016.

11. Valenzuela MJ, Jones M, Wen W, et al. Memory training alters hippocampal neurochemistry in healthy elderly. Neruroreport. 2013;14(10):1333-7. doi 10.1096/01.wrn.0000077 548.91466.05.

12. Loy C, Schneider L. Galantamine for Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2006;(1):CD001747.

13. Solis-Herrera C, Triplitt CL, Lynch JL. Nephropathy in youth and young adults with type 2 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14(2):456. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0456-y.

14. Urbina EM, Kimball TR, McCoy CE, Khoury PR, Daniels SR, Dolan LM. Youth with obesity and obesity-related type 2 diabetes mellitus demonstrate abnormalities in carotid structure and function. Circulation. 2009;119(22):2913-9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.830380.

15. Tsourdi E, Barthel A, Rietzsch H, Reichel A, Bornstein SR. Current aspects in the pathophysiology and treatment of chronic wounds in diabetes mellitus. BioMed Research Int. 2013;2013:385641. doi: 10.1155/2013/385641.

16. Simpson TC, Weldon JC, Worthington HV, et al. Treatment of periodontal disease for glycaemic control in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2015;(11): CD004714. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004714.pub3.