The information presented in the report reveals only what was spoken or visually presented on slides during the workshop, it is a prepublication report. Scientists with expertise in food safety, nutrition, pharmacology, psychology, toxicology, and related disciplines; medical professionals with pediatric and adult patient experience in cardiology, neurology, and psychiatry; public health professionals; food industry representatives; regulatory experts; and consumer advocates discussed the safety of caffeine in food and dietary supplements, including, but not limited to, caffeinated beverage products, and identified data gaps.

Caffeine, a central nervous stimulant, is arguably the most frequently ingested pharmacologically active substance in the world. Occurring naturally in more than 60 plants, including coffee beans, tea leaves, cola nuts and cocoa pods, caffeine has been part of countless cultures for centuries. However, the caffeine-in-food landscape is changing.

There are many new caffeine-containing energy products, such as waffles, sunflower seeds, jelly beans, syrup, and bottled water, entering the marketplace. Years of scientific research have shown that moderate consumption by healthy adults of products containing naturally occurring caffeine is not associated with adverse health effects. The changing caffeine landscape raises concerns about safety and whether any of these new products might be targeting populations not normally associated with caffeine consumption. This includes children and adolescents, and the question is whether caffeine poses a greater health risk to these groups than it does to healthy adults.

Soft drink in Brazil

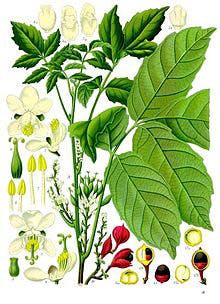

Some drinks also contain guarana, a double whammy! As a dietary supplement, guarana is an effective stimulant, its seeds contain about twice the concentration of caffeine found in coffee beans (about 2–4.5% caffeine in guarana seeds compared to 1–2% for coffee beans).(12) In the United States, guarana has received the designation of "generally recognized as safe" by the American Food and Drug Administration.

It is prudent to educate our patients about the effects of caffeine and energy drinks to their general and oral health. As well, they should be aware of the difference between energy drinks and sports drinks.