The Role of Dental Hygienists in Providing Access to Oral Health Care: Are you in charge of your future?

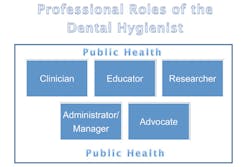

The Role of Dental Hygienists in Providing Access to Oral Health Care summarizes various policies governing the role of dental hygienists and examines alternative models and practices from states. To increase access to basic oral health, some states have explored policies that would permit and even encourage dental hygienists to practice outside dentists’ offices. Specifically, states have looked into altering supervision or reimbursement rules, as well as creating professional certifications for advanced-practice dental hygienists. Thus far, studies of pilot programs have shown safe and effective outcomes.

In spite of the fact that most oral health diseases are preventable, the rate of tooth decay, periodontal diseases, oral cancers, and other conditions is high. Data shows that certain population groups are disproportionally affected.(2) Low income people, minority ethnic groups, and low-income Americans are among these groups. About 25% of children have untreated tooth decay. The rate among low-income children is more than twice that for children with more income (31% versus 14%). African American and Hispanic children also have elevated rates compared to White children (28% and 29% versus 19%). Medicaid and CHIP cover comprehensive dental benefits for children, but 30% of children with private health insurance are uninsured for dental care.(2)