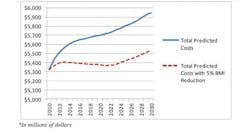

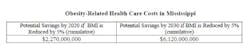

CDC has modernized the methodology for BRFSS this year, setting a new baseline for comparisons. The updated approach, incorporating cell phones and using an iterative proportional fitting data weighting method, means rates are even more reflective of each states’ population, but that the rates were determined in a different way than in the past, making direct change comparisons difficult. The full data set is available.(2)State-By-State Adult Obesity Rate Projections For 2030 Researchers calculated projections using a model published in The Lancet in 2011 and data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, which is an annual phone survey conducted by the CDC and state health departments. The data were adjusted for self-reporting bias. Adults are considered obese if their BMI is 30 or higher. The District of Columbia (D.C.) is included in the rankings because the CDC provides funds to D.C. to conduct a survey in an equivalent way to the states. The full methodology is available in the F as in Fat report.(3) 1. Mississippi (66.7%); 2. Oklahoma (66.4%); 3. Delaware (64.7%); 4. Tennessee (63.4%); 5. South Carolina (62.9%); 6. Alabama (62.6%); 7. Tie Kansas (62.1%); and Louisiana (62.1%); 9. Missouri (61.9%); 10. Arkansas (60.6%); 11. South Dakota (60.4%); 12. West Virginia (60.2%); 13. Kentucky (60.1%); 14. Ohio (59.8%); 15. Michigan (59.4%); 16. (tie) Arizona (58.8%); and Maryland (58.8%); 18. Florida (58.6%); 19. North Carolina (58.0%): 20. New Hampshire (57.7%); 21. Texas (57.2%); 22. North Dakota (57.1%); 23. Nebraska (56.9%); 24. Pennsylvania (56.7%); 25. Wyoming (56.6%); 26. Wisconsin (56.3%); 27. Indiana (56.0%); 28. Washington (55.5%); 29. Maine (55.2%): 30. Minnesota (54.7%); 31. Iowa (54.4%); 32. New Mexico (54.2%); 33. Rhode Island (53.8%); 34. Illinois (53.7%); 35. (tie) Georgia (53.6%); and Montana (53.6%); 37. Idaho (53.0%); 38. Hawaii (51.8%); 39. New York (50.9%); 40. Virginia (49.7%); 41. Nevada (49.6%); 42. Oregon (48.8%); 43. Massachusetts (48.7%); 44. New Jersey (48.6%); 45. Vermont (47.7%); 46. California (46.6%); 47. Connecticut (46.5%); 48. Utah (46.4%); 49. Alaska (45.6%); 50. Colorado (44.8%); 51. District of Columbia (32.6%). Note: 1 = Highest rate of adult obesity, 51 = lowest rate of adult obesity. State-By-State Potential Health Care Cost Savings By 2030 If States Reduce Average Body Mass Index By 5 Percent 1. California ($81,702,000,000); 2. Texas ($54,194,000,000); 3. New York ($40,017,000,000); 4. Florida ($34,436,000,000); 5. Illinois ($28,185,000,000); 6. Ohio ($26,328,000,000); 7. Pennsylvania ($24,498,000,000); 8. Michigan ($24,187,000,000); 9. Georgia ($22,743,000,000); 10. North Carolina ($21,101,000,000); 11. Virginia ($18,114,000,000); 12. Washington ($14,729,000,000); 13. Massachusetts ($14,055,000,000); 14. Maryland ($13,836,000,000); 15. Tennessee ($13,827,000,000); 16. Arizona ($13,642,000,000); 17. Indiana ($13,400,000,000); 18. Missouri ($13,368,000,000); 19. Wisconsin ($11,962,000,000); 20. Minnesota ($11,630,000,000); 21. Colorado ($10,794,000,000); 22. Louisiana ($9,839,000,000); 23. Alabama ($9,481,000,000); 24. Kentucky ($9,437,000,000); 25. South Carolina ($9,309,000,000); 26. Oregon ($7,938,000,000); 27. Oklahoma ($7,444,000,000); 28. Connecticut ($7,370,000,000); 29. Mississippi ($6,120,000,000); 30. Arkansas ($6,054,000,000); 31. Kansas ($5,979,000,000); 32. Nevada ($5,921,000,000); 33. Utah ($5,843,000,000); 34. Iowa ($5,702,000,000); 35. New Mexico ($4,095,000,000); 36. Nebraska ($3,686,000,000); 37. West Virginia ($3,638,000,000); 38. Idaho ($3,280,000,000); 39. New Hampshire ($3,257,000,000); 40. Maine ($2,870,000,000); 41. Hawaii ($2,704,000,000); 42. Rhode Island ($2,478,000,000); 43. Montana ($1,939,000,000); 44. Delaware ($1,912,000,000); 45. South Dakota ($1,553,000,000); 46. Alaska ($1,530,000,000); 47. New Jersey ($1,391,000,000); 48. Vermont ($1,376,000,000); 49. North Dakota ($1,177,000,000); 50. Wyoming ($1,088,000,000); 51. District of Columbia ($1,026,000,000). “Bending the Obesity Curve” is available for all states.(4) An example here represents Mississippi, with the highest rate of obesity in the country. Reducing the average body mass index in the state by 5 percent could lead to health care savings of more than $2 billion in 10 years and $6 billion in 20 years.Projections for Annual Obesity-Related Health Spending in Mississippi, 2010-2030