Breast cancer: the latest science

By Maria Perno Goldie, RDH, MS

Whether you are at risk (or have) breast cancer, or one of your patients’ does, this article will be of interest. In the United States, breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in women (excluding skin cancer). This year, the American Cancer Society (ACS) estimates that 230,480 women will be diagnosed with invasive breast cancer, and 57,650 cases of in situ breast cancer will occur. Additionally, an estimated 2,140 men will be diagnosed with breast cancer this year. The incidence of breast cancer in women has been decreasing since 2000. It decreased by about 7% between 2002 and 2003, which was likely due to fewer women using menopausal hormone therapy.Currently, there are more than two and a half million women living in the United States who have been diagnosed with and treated for breast cancer. For more oncologist-approved information about breast cancer, visit Cancer.Net, ASCO’s patient information website, at www.cancer.net/breast.The ABCs of Breast Density (August 2011)

You may have heard health reports about the importance of breast density on a mammogram (also called mammographic density), which has emerged as a strong risk factor for breast cancer in women. But what, exactly, is breast density? What is its role in breast cancer? How do you know if you have dense breasts? And, if you do have dense breasts, is there anything you can do to lower your breast cancer risk? Breast basics

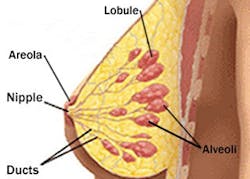

A woman's breasts are made up mostly of fat and breast tissue. Breast tissue is the network of lobules (sacs that produce milk) and ducts (canals that carry milk from the lobules to the nipple openings during breastfeeding). Connective tissue helps hold everything in place.

You may have heard health reports about the importance of breast density on a mammogram (also called mammographic density), which has emerged as a strong risk factor for breast cancer in women. But what, exactly, is breast density? What is its role in breast cancer? How do you know if you have dense breasts? And, if you do have dense breasts, is there anything you can do to lower your breast cancer risk? Breast basics

A woman's breasts are made up mostly of fat and breast tissue. Breast tissue is the network of lobules (sacs that produce milk) and ducts (canals that carry milk from the lobules to the nipple openings during breastfeeding). Connective tissue helps hold everything in place.

What is breast density?

Breast density is a way to describe the composition of a woman's breasts. This measure compares the area of breast and connective tissue seen on a mammogram to the area of fat. Breast and connective tissue are denser than fat and this difference shows up on a mammogram. • High breast density means there is a greater amount of breast and connective tissue compared to fat. • Low breast density means there is a greater amount of fat compared to breast and connective tissue. How is breast density measured?

Currently, there are several ways to measure breast density. All of these measures rely on a physician's visual assessment of the mammogram. Hence these assessments are somewhat subjective, and one physician's estimate of breast density may be different from another's. When the mammogram shows a breast is very dense or very fatty, agreement is high. However, when the mammogram shows something in between, agreement tends to be lower.(1) This is an issue with all current measures of breast density. The most common method is the American College of Radiology's Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) for breast density. This system, however, is not routinely reported or used by health care providers to assess breast cancer risk. The best way to measure breast density remains an active area of research. How do I know if I have dense breasts?

After looking at your mammogram, the radiologist may record breast density using BI-RADS or a similar measure. Using this measure or by looking at your mammogram itself, the radiologist may conclude that you have dense breasts. If your mammogram report does not include information about the radiologist's assessment of your breast density, you can ask your provider for this information. Breast density and breast cancer risk

High breast density, as seen on a mammogram, is linked to an increased risk of breast cancer. Women with very dense breasts are four to five times more likely to develop breast cancer than women with low breast density.(2-3) Breast density is clearly a risk factor for breast cancer, and researchers are trying to determine how to use information to assess individual risk, and someday be a risk factor that can be modified to reduce risk. Currently, it is not known why breast density is related to breast cancer. Researchers are looking into many possible mechanisms in the body that might explain this relationship.Factors related to breast density

Many factors related to breast density are also related to breast cancer. Learning more about these factors may help explain how breast density increases breast cancer risk. It may also provide clues for ways to lower breast cancer risk in women with dense breasts. Some of the factors shown to be related to breast density are discussed below. All of these factors and their role in breast density are still under study. Genetic factors

Having dense breasts appears to run in families and is likely related to some genetic factors. Specific genes that might be linked to breast density are under study.(4-7) Early life exposures

Growth and development in early life may impact breast density.(8) For example, higher birthweight appears to be related to higher breast density in adulthood.(9) And, higher body weight during adolescence may be related to lower breast density.(10) Pregnancy and childbearing

Breast density decreases somewhat with each pregnancy. Therefore, the more children a woman has given birth to, the less dense her breasts tend to be.(4,11-12) Similarly, the more children a woman has given birth to, the lower her risk of breast cancer.(13) Age and menopause

During menopause, hormone changes in the body cause the breast tissue to become less dense. In general, younger, premenopausal women have denser breasts than older, postmenopausal women. However, younger women who have gone through early menopause due to oophorectomy or total hysterectomy may have lower breast density. This is confusing: breast density decreases with age and yet, breast cancer risk increases with age. It may be that breast density plays an early role in the development of breast cancer, but at this time, researchers do not know. As more is discovered, these relationships should become clearer. Postmenopausal hormone use (estrogen plus progestin)

Women who use postmenopausal hormones (estrogen plus progestin) have higher breast density than women who do not use these hormones. Their breast density decreases when they stop using hormones.(14-15) Postmenopausal hormone use also increases the risk of breast cancer.(16-19) Recent findings suggest women who have high breast density may have an added risk of breast cancer (beyond the risk due to high breast density) if they use postmenopausal hormones.(20) Body weight

Breast density is related to body weight. Compared to women with higher breast density, women with lower breast density are more likely to have:(10) • Higher body weight in adulthood • Higher body weight during adolescence • Increased weight gain since age 18 Body weight affects breast cancer risk differently before and after menopause. Before menopause, being overweight offers modest protection against breast cancer in women. After menopause, being obese or overweight increases the risk of breast cancer.(21-23) As with age, these differences are confusing: breast density is lower among women with a higher body weight, yet, after menopause, higher body weight increases breast cancer risk. Although we do not yet understand the relationship between body weight, breast density and breast cancer risk, this topic is under active study. Screening for women with dense breasts

Mammography (digital mammography)On a mammogram, fat in the breast looks dark and the denser breast and connective tissues look light gray or white. Because cancer can also appear white on a mammogram, it is harder to interpret mammograms in women with dense breasts. Standard mammography produces an X-ray image on film, while digital mammography allows the image to be viewed on a computer screen. On the computer, certain sections of the X-ray image can be magnified and easily examined more closely, and the contrast of the image can be adjusted. This makes digital mammography better at finding tumors in women with dense breasts than standard film mammography.(24) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), in combination with mammography, is under study as a breast cancer screening tool for women with dense breasts.(25-26) Currently, the American Cancer Society (ACS) feels there is not enough evidence to recommend for or against MRI plus mammography screening for women with dense breasts. Rather, ACS suggests women with dense breasts talk to their health care providers about whether they should consider adding MRI to their annual mammography screening.(25) Ultrasound, in combination with mammography, is also under study as a breast cancer screening tool for women with dense breasts.(26) What if you have dense breasts?

At this time, there are no specific recommendations on lowering breast cancer risk for women with dense breasts. Although women with dense breasts appear to be at higher risk of breast cancer, it is not clear that lowering breast density will necessarily decrease risk of breast cancer. For example, getting older and gaining weight after menopause are both related to a decrease in breast density, but are also related to an increase in cancer risk. However, all women can take steps to lower their breast cancer risk (learn more about making healthy lifestyle choices). There are no special breast cancer screening tests recommended for women with dense breasts. However, if you have dense breasts, talk to your health care provider about which breast cancer screening tests are right for you. Susan G. Komen for the Cure recommends: 1. Know your risk • Talk to your family to learn about your family health history • Talk to your health care provider about your personal risk of breast cancer 2. Get screened • Ask your health care provider which screening tests are right for you if you are at a higher risk • Have a mammogram every year starting at age 40 if you are at average risk • Have a clinical breast exam at least every three years starting at age 20, and every year starting at age 40 3. Know what is normal for you and see your health care provider if you notice any of these breast changes: • Lump, hard knot or thickening inside the breast • Swelling, warmth, redness or darkening of the breast • Change in the size or shape of the breast • Dimpling or puckering of the skin • Itchy, scaly sore or rash on the nipple • Pulling in of your nipple or other parts of the breast • Nipple discharge that starts suddenly • New pain in one spot that doesn't go away 4. Make healthy lifestyle choices • Maintain a healthy weight • Add exercise into your routine • Limit alcohol intake • Limit postmenopausal hormone use • Breastfeed, if you can Survival

Currently, there are more than two and a half million women living in the United States who have been diagnosed with and treated for breast cancer.

Breast density is a way to describe the composition of a woman's breasts. This measure compares the area of breast and connective tissue seen on a mammogram to the area of fat. Breast and connective tissue are denser than fat and this difference shows up on a mammogram. • High breast density means there is a greater amount of breast and connective tissue compared to fat. • Low breast density means there is a greater amount of fat compared to breast and connective tissue. How is breast density measured?

Currently, there are several ways to measure breast density. All of these measures rely on a physician's visual assessment of the mammogram. Hence these assessments are somewhat subjective, and one physician's estimate of breast density may be different from another's. When the mammogram shows a breast is very dense or very fatty, agreement is high. However, when the mammogram shows something in between, agreement tends to be lower.(1) This is an issue with all current measures of breast density. The most common method is the American College of Radiology's Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) for breast density. This system, however, is not routinely reported or used by health care providers to assess breast cancer risk. The best way to measure breast density remains an active area of research. How do I know if I have dense breasts?

After looking at your mammogram, the radiologist may record breast density using BI-RADS or a similar measure. Using this measure or by looking at your mammogram itself, the radiologist may conclude that you have dense breasts. If your mammogram report does not include information about the radiologist's assessment of your breast density, you can ask your provider for this information. Breast density and breast cancer risk

High breast density, as seen on a mammogram, is linked to an increased risk of breast cancer. Women with very dense breasts are four to five times more likely to develop breast cancer than women with low breast density.(2-3) Breast density is clearly a risk factor for breast cancer, and researchers are trying to determine how to use information to assess individual risk, and someday be a risk factor that can be modified to reduce risk. Currently, it is not known why breast density is related to breast cancer. Researchers are looking into many possible mechanisms in the body that might explain this relationship.Factors related to breast density

Many factors related to breast density are also related to breast cancer. Learning more about these factors may help explain how breast density increases breast cancer risk. It may also provide clues for ways to lower breast cancer risk in women with dense breasts. Some of the factors shown to be related to breast density are discussed below. All of these factors and their role in breast density are still under study. Genetic factors

Having dense breasts appears to run in families and is likely related to some genetic factors. Specific genes that might be linked to breast density are under study.(4-7) Early life exposures

Growth and development in early life may impact breast density.(8) For example, higher birthweight appears to be related to higher breast density in adulthood.(9) And, higher body weight during adolescence may be related to lower breast density.(10) Pregnancy and childbearing

Breast density decreases somewhat with each pregnancy. Therefore, the more children a woman has given birth to, the less dense her breasts tend to be.(4,11-12) Similarly, the more children a woman has given birth to, the lower her risk of breast cancer.(13) Age and menopause

During menopause, hormone changes in the body cause the breast tissue to become less dense. In general, younger, premenopausal women have denser breasts than older, postmenopausal women. However, younger women who have gone through early menopause due to oophorectomy or total hysterectomy may have lower breast density. This is confusing: breast density decreases with age and yet, breast cancer risk increases with age. It may be that breast density plays an early role in the development of breast cancer, but at this time, researchers do not know. As more is discovered, these relationships should become clearer. Postmenopausal hormone use (estrogen plus progestin)

Women who use postmenopausal hormones (estrogen plus progestin) have higher breast density than women who do not use these hormones. Their breast density decreases when they stop using hormones.(14-15) Postmenopausal hormone use also increases the risk of breast cancer.(16-19) Recent findings suggest women who have high breast density may have an added risk of breast cancer (beyond the risk due to high breast density) if they use postmenopausal hormones.(20) Body weight

Breast density is related to body weight. Compared to women with higher breast density, women with lower breast density are more likely to have:(10) • Higher body weight in adulthood • Higher body weight during adolescence • Increased weight gain since age 18 Body weight affects breast cancer risk differently before and after menopause. Before menopause, being overweight offers modest protection against breast cancer in women. After menopause, being obese or overweight increases the risk of breast cancer.(21-23) As with age, these differences are confusing: breast density is lower among women with a higher body weight, yet, after menopause, higher body weight increases breast cancer risk. Although we do not yet understand the relationship between body weight, breast density and breast cancer risk, this topic is under active study. Screening for women with dense breasts

Mammography (digital mammography)On a mammogram, fat in the breast looks dark and the denser breast and connective tissues look light gray or white. Because cancer can also appear white on a mammogram, it is harder to interpret mammograms in women with dense breasts. Standard mammography produces an X-ray image on film, while digital mammography allows the image to be viewed on a computer screen. On the computer, certain sections of the X-ray image can be magnified and easily examined more closely, and the contrast of the image can be adjusted. This makes digital mammography better at finding tumors in women with dense breasts than standard film mammography.(24) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), in combination with mammography, is under study as a breast cancer screening tool for women with dense breasts.(25-26) Currently, the American Cancer Society (ACS) feels there is not enough evidence to recommend for or against MRI plus mammography screening for women with dense breasts. Rather, ACS suggests women with dense breasts talk to their health care providers about whether they should consider adding MRI to their annual mammography screening.(25) Ultrasound, in combination with mammography, is also under study as a breast cancer screening tool for women with dense breasts.(26) What if you have dense breasts?

At this time, there are no specific recommendations on lowering breast cancer risk for women with dense breasts. Although women with dense breasts appear to be at higher risk of breast cancer, it is not clear that lowering breast density will necessarily decrease risk of breast cancer. For example, getting older and gaining weight after menopause are both related to a decrease in breast density, but are also related to an increase in cancer risk. However, all women can take steps to lower their breast cancer risk (learn more about making healthy lifestyle choices). There are no special breast cancer screening tests recommended for women with dense breasts. However, if you have dense breasts, talk to your health care provider about which breast cancer screening tests are right for you. Susan G. Komen for the Cure recommends: 1. Know your risk • Talk to your family to learn about your family health history • Talk to your health care provider about your personal risk of breast cancer 2. Get screened • Ask your health care provider which screening tests are right for you if you are at a higher risk • Have a mammogram every year starting at age 40 if you are at average risk • Have a clinical breast exam at least every three years starting at age 20, and every year starting at age 40 3. Know what is normal for you and see your health care provider if you notice any of these breast changes: • Lump, hard knot or thickening inside the breast • Swelling, warmth, redness or darkening of the breast • Change in the size or shape of the breast • Dimpling or puckering of the skin • Itchy, scaly sore or rash on the nipple • Pulling in of your nipple or other parts of the breast • Nipple discharge that starts suddenly • New pain in one spot that doesn't go away 4. Make healthy lifestyle choices • Maintain a healthy weight • Add exercise into your routine • Limit alcohol intake • Limit postmenopausal hormone use • Breastfeed, if you can Survival

Currently, there are more than two and a half million women living in the United States who have been diagnosed with and treated for breast cancer.

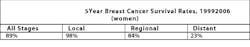

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in women. The ACS estimates that 39,970 deaths (39,520 women, 450 men) from breast cancer will occur this year. Since 1990, the number of women who have died of breast cancer has declined steadily each year. In women younger than 50, there has been a decrease of around 3% per year; in women age 50 and older, the decrease has been 2% per year.Risk Factors

Many women who develop breast cancer have no obvious risk factors. However, research has shown that the following factors may increase a women’s risk of breast cancer:• Older age (above 50)• Family or personal history of breast cancer or ovarian cancer• Genetics, such as BRCA gene mutations• Estrogen and progesterone exposure• Menopausal hormone therapy use• Race• Lifestyle factors, such as obesity, lack of exercise, and alcohol useFor more information on risk factors, visit www.cancer.net/patient/Cancer+Types/Breast+Cancer.Prevention

No intervention is 100% guaranteed to prevent breast cancer. However, women have several options to reduce the risk of developing breast cancer.• Women with especially strong family histories of breast cancer (such as those with BRCA gene mutations) may consider a prophylactic mastectomy, which may reduce the risk of developing breast cancer by at least 95%.• Women with a higher risk of developing breast cancer may consider chemoprevention with either tamoxifen (Nolvadex) or raloxifene (Evista). Read about drugs to reduce breast cancer risk. www.cancer.net/patient/Publications+and+Resources/What+to+Know%3A+ASCO%27s+Guidelines/What+to+Know%3A+ASCO%27s+Guideline+on+Drugs+to+Lower+Breast+Cancer+Risk• Getting regular physical activity, staying at a normal weight, and limiting alcohol may also help reduce the risk of developing breast cancer. Learn more about lifestyle changes to reduce the risk of cancer. www.cancer.net/patient/All+About+Cancer/Risk+Factors+and+PreventionScreening

Mammography is the best tool doctors have to screen otherwise healthy women for breast cancer, as it has been shown to lower deaths from breast cancer. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the ACS differ on their recommendations for breast cancer screening.Mammography

• ACS recommendation: Women 40 and older should have one every year after a clinical breast examination (see below).• USPSTF recommendation: Women 50 to 74 years old should have one every two years. There is not enough evidence to assess the additional harms and benefits of mammography for women 75 and older.Clinical breast examination• ACS recommendation: Women 20 to 40 years old should have one at least every three years. Women 40 and older should have one every year.• USPSTF recommendation: The current evidence is insufficient to assess the additional benefits and harms of clinical breast examination beyond screening mammography in women 40 years or older.Breast self-examination• ACS recommendation: Women 20 and older should be told about the benefits and limitations of this examination and the importance of talking with the doctor about any breast changes. This examination is considered "optional." However, if a woman chooses to perform breast self-examinations, she should have her doctor review her method at periodic check-ups.• USPSTF recommendation: Recommends against teaching breast self-examination.From ASCO's perspective, the critical message is that all women--beginning at age 40--should speak with their doctors about mammography to understand the benefits and potential risks, and determine what is best for them. Learn more about ASCO’s perspective on mammography screening for breast cancer. www.cancer.net/patient/Cancer+News+and+Meetings/Expert+Perspective+on+Cancer+News/Expert+Perspective+from+ASCO+on+Mammography+Screening+for+Breast+CancerFor oncologist-approved patient information resources, visit www.Cancer.Net, ASCO’s patient Website.Source: Cancer Facts & Figures 2011. Atlanta, GA; American Cancer Society: 2011.

Many women who develop breast cancer have no obvious risk factors. However, research has shown that the following factors may increase a women’s risk of breast cancer:• Older age (above 50)• Family or personal history of breast cancer or ovarian cancer• Genetics, such as BRCA gene mutations• Estrogen and progesterone exposure• Menopausal hormone therapy use• Race• Lifestyle factors, such as obesity, lack of exercise, and alcohol useFor more information on risk factors, visit www.cancer.net/patient/Cancer+Types/Breast+Cancer.Prevention

No intervention is 100% guaranteed to prevent breast cancer. However, women have several options to reduce the risk of developing breast cancer.• Women with especially strong family histories of breast cancer (such as those with BRCA gene mutations) may consider a prophylactic mastectomy, which may reduce the risk of developing breast cancer by at least 95%.• Women with a higher risk of developing breast cancer may consider chemoprevention with either tamoxifen (Nolvadex) or raloxifene (Evista). Read about drugs to reduce breast cancer risk. www.cancer.net/patient/Publications+and+Resources/What+to+Know%3A+ASCO%27s+Guidelines/What+to+Know%3A+ASCO%27s+Guideline+on+Drugs+to+Lower+Breast+Cancer+Risk• Getting regular physical activity, staying at a normal weight, and limiting alcohol may also help reduce the risk of developing breast cancer. Learn more about lifestyle changes to reduce the risk of cancer. www.cancer.net/patient/All+About+Cancer/Risk+Factors+and+PreventionScreening

Mammography is the best tool doctors have to screen otherwise healthy women for breast cancer, as it has been shown to lower deaths from breast cancer. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the ACS differ on their recommendations for breast cancer screening.Mammography

• ACS recommendation: Women 40 and older should have one every year after a clinical breast examination (see below).• USPSTF recommendation: Women 50 to 74 years old should have one every two years. There is not enough evidence to assess the additional harms and benefits of mammography for women 75 and older.Clinical breast examination• ACS recommendation: Women 20 to 40 years old should have one at least every three years. Women 40 and older should have one every year.• USPSTF recommendation: The current evidence is insufficient to assess the additional benefits and harms of clinical breast examination beyond screening mammography in women 40 years or older.Breast self-examination• ACS recommendation: Women 20 and older should be told about the benefits and limitations of this examination and the importance of talking with the doctor about any breast changes. This examination is considered "optional." However, if a woman chooses to perform breast self-examinations, she should have her doctor review her method at periodic check-ups.• USPSTF recommendation: Recommends against teaching breast self-examination.From ASCO's perspective, the critical message is that all women--beginning at age 40--should speak with their doctors about mammography to understand the benefits and potential risks, and determine what is best for them. Learn more about ASCO’s perspective on mammography screening for breast cancer. www.cancer.net/patient/Cancer+News+and+Meetings/Expert+Perspective+on+Cancer+News/Expert+Perspective+from+ASCO+on+Mammography+Screening+for+Breast+CancerFor oncologist-approved patient information resources, visit www.Cancer.Net, ASCO’s patient Website.Source: Cancer Facts & Figures 2011. Atlanta, GA; American Cancer Society: 2011.

Breast Cancer Symposium, September 2011

New studies on breast cancer screening, treatment, and survival were released September 6, 2011 in advance of the 2011 Breast Cancer Symposium. The symposium was held September 8-10, 2011, at the San Francisco Marriott Marquis in San Francisco.Breast cancer in women under 40 is often diagnosed at a later stage compared to women > 40. Young age at diagnosis has been shown to be an independent risk factor for recurrence, even after controlling for stage at diagnosis. Prior studies have shown that younger women have higher rates of local recurrence (breast and/or axilla) after lumpectomy. This study sought to determine the risk of local and distant recurrence in young women in the modern era of multimodal therapy for breast cancer.The overall rates of local recurrence (breast and/or axilla) were 5.6% at 5 years and 13% at 10 years. The overall rates of distant recurrence were 12% at 5 years and 19% at 10 years. There was no significant difference in the rates of local recurrence between patients who had mastectomy (12/161) and patients who had a lumpectomy(30/421). The conclusion was that women aged 40 and under diagnosed with breast cancer today have a good prognosis with a low risk of breast cancer recurrence at 5 and 10 years.(27)A new statistical tool may predict risk of common debilitating side effect of lymphedema associated with breast cancer surgery. Researchers have created a set of statistical models that are more than 70 percent accurate for predicting the five-year risk of developing lymphedema (debilitating swelling) after lymph node removal during breast cancer surgery. Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) is done in about 25% of patients with Breast Cancer. Secondary lymphedema (LE) occurs in about 30% of patents submitted to ALND. Up to 150,000 women develop LE each year worldwide. Over 4 million people are currently alive and suffering from LE related to breast cancer treatment. Several risk factors for LE have been identified in the literature. Usually the results of these studies are expressed as relative risk (odds ratio or hazard ratio). It is difficult to apply accumulated knowledge when estimating the risk of LE in an individual patient. Absolute risk is easier to be used in an individual patient.The conclusions of one study stated that the 5-year cumulative incidence of LE was 30.3%. They have developed a free online arm volume calculator (www.armvolume.com). Their analyses suggest that the nomograms accurately estimate the probability of LE. The researchers have developed a free version of the nomogram models (www.lymphedemarisk.com), which it will soon be available after the paper’s publication (www.lymphedemarisk.com).(28)A large Michigan study suggests continued importance of self-exams, and annual mammography in breast cancer detection, even in younger women. An analysis of breast cancer diagnosis data from nearly 6,000 women in Michigan suggests that mammography and self-breast exams remain important tools for detecting breast cancer, even among women aged 40 to 49 for whom routine mammography has been questioned by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).(29)

New studies on breast cancer screening, treatment, and survival were released September 6, 2011 in advance of the 2011 Breast Cancer Symposium. The symposium was held September 8-10, 2011, at the San Francisco Marriott Marquis in San Francisco.Breast cancer in women under 40 is often diagnosed at a later stage compared to women > 40. Young age at diagnosis has been shown to be an independent risk factor for recurrence, even after controlling for stage at diagnosis. Prior studies have shown that younger women have higher rates of local recurrence (breast and/or axilla) after lumpectomy. This study sought to determine the risk of local and distant recurrence in young women in the modern era of multimodal therapy for breast cancer.The overall rates of local recurrence (breast and/or axilla) were 5.6% at 5 years and 13% at 10 years. The overall rates of distant recurrence were 12% at 5 years and 19% at 10 years. There was no significant difference in the rates of local recurrence between patients who had mastectomy (12/161) and patients who had a lumpectomy(30/421). The conclusion was that women aged 40 and under diagnosed with breast cancer today have a good prognosis with a low risk of breast cancer recurrence at 5 and 10 years.(27)A new statistical tool may predict risk of common debilitating side effect of lymphedema associated with breast cancer surgery. Researchers have created a set of statistical models that are more than 70 percent accurate for predicting the five-year risk of developing lymphedema (debilitating swelling) after lymph node removal during breast cancer surgery. Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) is done in about 25% of patients with Breast Cancer. Secondary lymphedema (LE) occurs in about 30% of patents submitted to ALND. Up to 150,000 women develop LE each year worldwide. Over 4 million people are currently alive and suffering from LE related to breast cancer treatment. Several risk factors for LE have been identified in the literature. Usually the results of these studies are expressed as relative risk (odds ratio or hazard ratio). It is difficult to apply accumulated knowledge when estimating the risk of LE in an individual patient. Absolute risk is easier to be used in an individual patient.The conclusions of one study stated that the 5-year cumulative incidence of LE was 30.3%. They have developed a free online arm volume calculator (www.armvolume.com). Their analyses suggest that the nomograms accurately estimate the probability of LE. The researchers have developed a free version of the nomogram models (www.lymphedemarisk.com), which it will soon be available after the paper’s publication (www.lymphedemarisk.com).(28)A large Michigan study suggests continued importance of self-exams, and annual mammography in breast cancer detection, even in younger women. An analysis of breast cancer diagnosis data from nearly 6,000 women in Michigan suggests that mammography and self-breast exams remain important tools for detecting breast cancer, even among women aged 40 to 49 for whom routine mammography has been questioned by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).(29)

Breast tumor on mammogram (indicated in photo above by red arrow)One last comment, about hereditary breast cancer. Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer seems to have an earlier onset with each generation. Younger age at diagnosis in subsequent generations of BRCA carriers indicates the importance of early breast screening.Women who carry BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations have elevated lifetime prevalence of breast and ovarian malignancies.(30) In an analysis conducted at one large U.S. cancer center, 303 women from 106 families with deleterious BRCA mutations in two or more generations were identified. All women had breast or ovarian cancer; age at diagnosis was compared between generations. Median age at diagnosis of breast or ovarian cancer was 48 years (range, 23–70) in the older generation and 42 years (range, 20–86) in the younger generation.In summary, there is much information available on breast cancer. Educate yourself for your sake, and that of your patients.References

1. Nicholson BT, LoRusso AP, Smolkin M, Bovbjerg VE, Petroni GR, Harvey JA. Accuracy of assigned BI-RADS breast density category definitions. Acad Radiol. 13(9):1143-9, 2006. 2. Boyd NF, Guo H, Martin LJ, et al. Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 356(3):227-36, 2007. 3. Tamimi RM, Byrne C, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. Endogenous hormone levels, mammographic density, and subsequent risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 99(15):1178-87, 2007. 4. Boyd NF, Dite GS, Stone J, et al. Heritability of mammographic density, a risk factor for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 347(12):886-94, 2002. 5. Stone J, Dite GS, Gunasekara A, et al. The heritability of mammographically dense and nondense breast tissue. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 15(4):612-7, 2006. 6. Ursin G, Lillie EO, Lee E, et al. The relative importance of genetics and environment on mammographic density. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 18(1):102-12, 2009. 7. Martin LJ, Melnichouk O, Guo H, et al. Family history, mammographic density, and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 19(2):456-63, 2010. 8. Boyd N, Martin L, Chavez S, et al. Breast-tissue composition and other risk factors for breast cancer in young women: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Oncol. 10(6):569-80, 2009. 9. Tamimi RM, Eriksson L, Lagiou P, et al. Birth weight and mammographic density among postmenopausal women in Sweden. Int J Cancer. 126(4):985-91, 2010. 10. Samimi G, Colditz GA, Baer HJ, Tamimi RM. Measures of energy balance and mammographic density in the Nurses' Health Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 109(1):113-22, 2008. 11. Li T, Sun L, Miller N, et al. The association of measured breast tissue characteristics with mammographic density and other risk factors for breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 14(2):343-9, 2005. 12. Dite GS, Gurrin LC, Byrnes GB, et al. Predictors of mammographic density: insights gained from a novel regression analysis of a twin study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 17(12):3474-81, 2008. 13. Willett WC, Tamimi RM, Hankinson SE, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA. Chapter 20: Nongenetic Factors in the Causation of Breast Cancer, in Harris JR, Lippman ME, Morrow M, Osborne CK. Diseases of the Breast, 4th edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010. 14. Rutter CM, Mandelson MT, Laya MB, Seger DJ, Taplin S. Changes in breast density associated with initiation, discontinuation, and continuing use of hormone replacement therapy. JAMA. 285(2):171-6, 2001. 15. McTiernan A, Martin CF, Peck JD, et al. for the Women's Health Initiative Mammogram Density Study Investigators. Estrogen-plus-progestin use and mammographic density in postmenopausal women: Women's Health Initiative randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 97(18):1366-76, 2005. 16. Colditz GA, Hankinson SE, Hunter DJ, et al. The use of estrogens and progestins and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 332: 1589-93, 1995. 17. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy: collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiological studies of 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108,411 women without breast cancer. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Lancet. 350: 1047-59, 1997. 18. Ross RK, Paganini-Hill A, Wan PC and Pike MC. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk: estrogen versus estrogen plus progestin. J Natl Cancer Inst. 92:328-32, 2000. 19. Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 288(3):321-33, 2002. 20. Kerlikowske K, Cook AJ, Buist DS, et al. Breast cancer risk by breast density, menopause, and postmenopausal hormone therapy use. J Clin Oncol. 28(24):3830-7, 2010. 21. Huang Z, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, et al. Dual effects of weight and weight gain on breast cancer risk. JAMA. 278: 1407-11, 1997. 22. van den Brandt PA, Speigelman D, Yaun S, et al. Pooled Analysis of Prospective Cohort on Height, Weight, and Breast Cancer Risk. American Journal of Epidemiology. 152(6):514-527, 2000. 23. Reeves GK, Pirie K, Beral V, Green J, Spencer E, Bull D. Cancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the Million Women Study: cohort study. BMJ. 335(7630):1134, 2007.Boyd NF, Martin LJ, Sun L, et al. Body size, mammographic density, and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 15(11):2086-92, 2006. 24. Pisano ED, Hendrick RE, Yaffe MJ, et al. for the DMIST Investigators Group. Diagnostic accuracy of digital versus film mammography: exploratory analysis of selected population subgroups in DMIST. Radiology. 246(2):376-83, 2008. 25. Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al. for the American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 57(2):75-89, 2007. 26. Pinsky RW, Helvie MA. Mammographic breast density: effect on imaging and breast cancer risk. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 8(10):1157-64, 2010. 27. Buckley JM, Coopey SB, Samphao S, Niemierko A, Specht MC, Hughes KS, Gadd MA, and Taghian AG. Recurrence Rates and Long Term Survival in Women Diagnosed With Breast Cancer at Age 40 and Younger. Abstract presented at the Breast Cancer Sympoiusm, 2011. 28. Bevilacqua, JLB; Kattan, MW; Yu,C; Koifman,S; Mattos, IE; Koifman,RJ; Bergmann, A. Nomograms for predicting the risk of arm lymphedema after axillary dissection in breast cancer. Abstract presented at the Breast Cancer Sympoiusm, 2011. 29. Smith DR, Caughran J, Kreinbrink JL, Parish GK, Silver SM, Breslin TM, Pettinga JE, Mehringer AM, Wesen CA, Yin H, Share D, Davis AT, Pleban FT, and Bacon-Baguley TA. Clinical presentation of breast cancer: Age, stage, and treatment modalities in a contemporary cohort of Michigan women. Abstract presented at the Breast Cancer Sympoiusm, 2011. 30. Litton JK, AU Ready K, Chen H, Gutierrez-Barrera A, Etzel CJ, Meric-Bernstam F, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Le-Petross H, Lu K, Hortobagyi GN, and Arun BK. Earlier age of onset of BRCA mutation-related cancers in subsequent generations. Cancer, 1097-0142, 2011, Sep 12.

1. Nicholson BT, LoRusso AP, Smolkin M, Bovbjerg VE, Petroni GR, Harvey JA. Accuracy of assigned BI-RADS breast density category definitions. Acad Radiol. 13(9):1143-9, 2006. 2. Boyd NF, Guo H, Martin LJ, et al. Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 356(3):227-36, 2007. 3. Tamimi RM, Byrne C, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. Endogenous hormone levels, mammographic density, and subsequent risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 99(15):1178-87, 2007. 4. Boyd NF, Dite GS, Stone J, et al. Heritability of mammographic density, a risk factor for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 347(12):886-94, 2002. 5. Stone J, Dite GS, Gunasekara A, et al. The heritability of mammographically dense and nondense breast tissue. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 15(4):612-7, 2006. 6. Ursin G, Lillie EO, Lee E, et al. The relative importance of genetics and environment on mammographic density. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 18(1):102-12, 2009. 7. Martin LJ, Melnichouk O, Guo H, et al. Family history, mammographic density, and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 19(2):456-63, 2010. 8. Boyd N, Martin L, Chavez S, et al. Breast-tissue composition and other risk factors for breast cancer in young women: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Oncol. 10(6):569-80, 2009. 9. Tamimi RM, Eriksson L, Lagiou P, et al. Birth weight and mammographic density among postmenopausal women in Sweden. Int J Cancer. 126(4):985-91, 2010. 10. Samimi G, Colditz GA, Baer HJ, Tamimi RM. Measures of energy balance and mammographic density in the Nurses' Health Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 109(1):113-22, 2008. 11. Li T, Sun L, Miller N, et al. The association of measured breast tissue characteristics with mammographic density and other risk factors for breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 14(2):343-9, 2005. 12. Dite GS, Gurrin LC, Byrnes GB, et al. Predictors of mammographic density: insights gained from a novel regression analysis of a twin study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 17(12):3474-81, 2008. 13. Willett WC, Tamimi RM, Hankinson SE, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA. Chapter 20: Nongenetic Factors in the Causation of Breast Cancer, in Harris JR, Lippman ME, Morrow M, Osborne CK. Diseases of the Breast, 4th edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010. 14. Rutter CM, Mandelson MT, Laya MB, Seger DJ, Taplin S. Changes in breast density associated with initiation, discontinuation, and continuing use of hormone replacement therapy. JAMA. 285(2):171-6, 2001. 15. McTiernan A, Martin CF, Peck JD, et al. for the Women's Health Initiative Mammogram Density Study Investigators. Estrogen-plus-progestin use and mammographic density in postmenopausal women: Women's Health Initiative randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 97(18):1366-76, 2005. 16. Colditz GA, Hankinson SE, Hunter DJ, et al. The use of estrogens and progestins and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 332: 1589-93, 1995. 17. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy: collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiological studies of 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108,411 women without breast cancer. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Lancet. 350: 1047-59, 1997. 18. Ross RK, Paganini-Hill A, Wan PC and Pike MC. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk: estrogen versus estrogen plus progestin. J Natl Cancer Inst. 92:328-32, 2000. 19. Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 288(3):321-33, 2002. 20. Kerlikowske K, Cook AJ, Buist DS, et al. Breast cancer risk by breast density, menopause, and postmenopausal hormone therapy use. J Clin Oncol. 28(24):3830-7, 2010. 21. Huang Z, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, et al. Dual effects of weight and weight gain on breast cancer risk. JAMA. 278: 1407-11, 1997. 22. van den Brandt PA, Speigelman D, Yaun S, et al. Pooled Analysis of Prospective Cohort on Height, Weight, and Breast Cancer Risk. American Journal of Epidemiology. 152(6):514-527, 2000. 23. Reeves GK, Pirie K, Beral V, Green J, Spencer E, Bull D. Cancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the Million Women Study: cohort study. BMJ. 335(7630):1134, 2007.Boyd NF, Martin LJ, Sun L, et al. Body size, mammographic density, and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 15(11):2086-92, 2006. 24. Pisano ED, Hendrick RE, Yaffe MJ, et al. for the DMIST Investigators Group. Diagnostic accuracy of digital versus film mammography: exploratory analysis of selected population subgroups in DMIST. Radiology. 246(2):376-83, 2008. 25. Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al. for the American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 57(2):75-89, 2007. 26. Pinsky RW, Helvie MA. Mammographic breast density: effect on imaging and breast cancer risk. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 8(10):1157-64, 2010. 27. Buckley JM, Coopey SB, Samphao S, Niemierko A, Specht MC, Hughes KS, Gadd MA, and Taghian AG. Recurrence Rates and Long Term Survival in Women Diagnosed With Breast Cancer at Age 40 and Younger. Abstract presented at the Breast Cancer Sympoiusm, 2011. 28. Bevilacqua, JLB; Kattan, MW; Yu,C; Koifman,S; Mattos, IE; Koifman,RJ; Bergmann, A. Nomograms for predicting the risk of arm lymphedema after axillary dissection in breast cancer. Abstract presented at the Breast Cancer Sympoiusm, 2011. 29. Smith DR, Caughran J, Kreinbrink JL, Parish GK, Silver SM, Breslin TM, Pettinga JE, Mehringer AM, Wesen CA, Yin H, Share D, Davis AT, Pleban FT, and Bacon-Baguley TA. Clinical presentation of breast cancer: Age, stage, and treatment modalities in a contemporary cohort of Michigan women. Abstract presented at the Breast Cancer Sympoiusm, 2011. 30. Litton JK, AU Ready K, Chen H, Gutierrez-Barrera A, Etzel CJ, Meric-Bernstam F, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Le-Petross H, Lu K, Hortobagyi GN, and Arun BK. Earlier age of onset of BRCA mutation-related cancers in subsequent generations. Cancer, 1097-0142, 2011, Sep 12.

Maria Perno Goldie, RDH, MS

To read previous articles in RDH eVillage FOCUS from 2011 written by Maria Perno Goldie, go to articles.