Management of a complex lower second molar: discussion of a clinical case

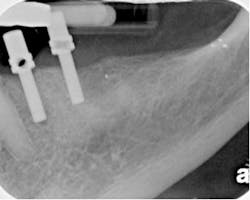

Fig. 1: The initial appearance of the clinical case described. At the time of the clinical examination in my office, the patient was asymptomatic. Percussion, palpation, mobility, and probings were all within normal limits. The tooth had been sealed with a temporary filling after the second visit. From the radiograph, it appeared that the tooth had one conical root with one canal located and shaped. A periapical lesion appeared to be developing at the apex of No. 18. The tooth was restorable. Radiographically, the canal was continuous from the orifice to the apex. The apex was open, patent, and negotiable. The patient’s opening was limited. Access to the tooth was poor. Consent for treatment was obtained. The procedure, alternatives, and risks were explained to the patient and questions were answered. Part of the consent for treatment focused on root anatomy. A single conical root on a lower second molar poses a long-term vertical root fracture risk from a number of different sources including bruxism. In any event, evaluating this case before starting revealed several challenges and considerations:

- The limited opening reduced the vertical space available for rotary nickel titanium (RNT) instruments to shape the canals.

- With another clinician having been into the tooth twice, the possibility of apical transportation and perforation was considered. Clinically, this meant that the risk of master cone and sealer extrusion upon downpack was significant.

- The working length needed determination ideally before the final canal shaping was completed. From the initial radiograph, it was not clear what the estimated working length was (in essence, was this tooth 17 mm or 20 mm?). Rather than immediately putting a RNT file down the tooth and exacerbating a possible apical perforation, it was important to first determine the true working length and then perform the final shaping. A second canal was deemed highly unlikely.

- The tooth should have been completed in one visit. There was no indication for the two visits that stretched into a third in this case. Given the fact that the tooth was vital, irreversibly inflamed and the patient without swelling, this clinical case was indicated for one visit treatment.

- The use of formocresol was entirely unnecessary and contraindicated. Had the tooth been treated in one visit, an interappointment medication would have been irrelevant. In the unusual clinical case where a vital tooth requires two visits (for an arbitrarily imposed reason determined by the clinician), either no medication is required (assuming that a pulpotomy or pulpectomy was performed) or calcium hydroxide could be used.

- Accurately determining the position of the MC was critical in the completion of this tooth as it was referred. Incorrect true working length determination (given how open and straight the canal is) could easily have transported the apex and lead to a significant extrusion of filling materials.